“Houston, we’ve had a problem”: In 1970 during the Apollo 13 — which was to be the third lunar landing mission, an oxygen tank of the spacecraft exploded and damaged the ship. The explosion changed the spacecraft’s trajectory. Without oxygen, needed for electricity and for breathing, both propulsion and life support systems could not function. Quickly, the mission control team in Houston had to identify the best strategies to safely bring the crew back home.

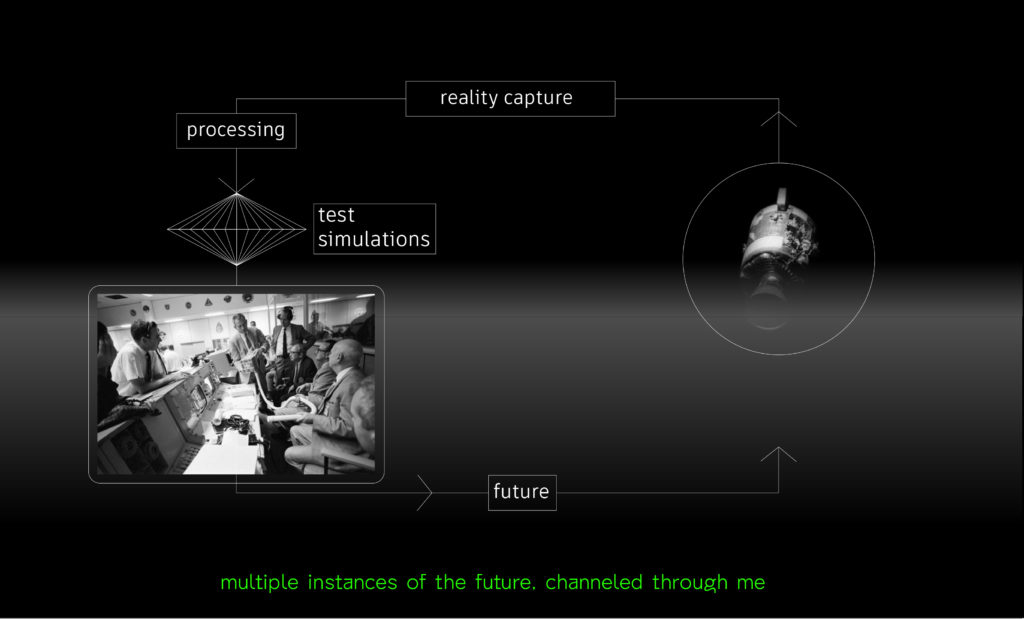

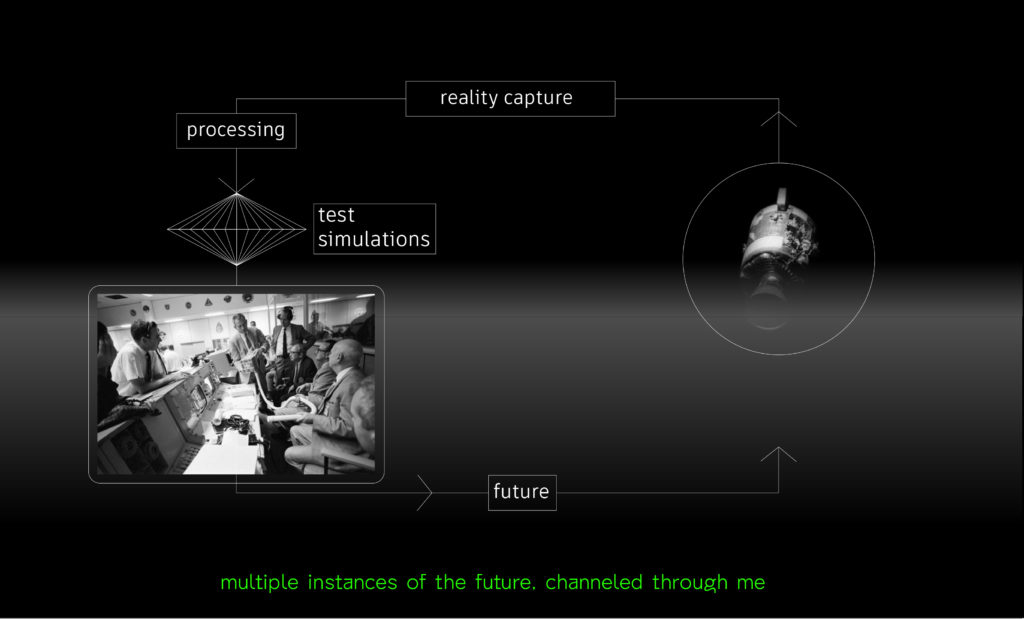

The Apollo 13 mission is known as the first use of a so-called digital twin — a digital instance of a physical entity, object, system, or person that can be updated in real time to reflect the changes in its target system (so-called physical twin).1 With the continuous stream of data from the spacecraft and the reports of the crew, the command control team was able to modify computer simulations of the mission and the physical models of the ship to reflect the unfolding changes in its state, and to test and determine strategies for action. This proto digital twin made up of coordinated simulators, computer systems, and full-scale physical models was a critical device used both as a training site for crew and command control, and as a design tool for the development of mission protocols and scenarios. Lastly, after the accident, it played an integral role in returning the crew back to Earth.

50 years after the successful failure2 of Apollo 13, digital twin technology is made possible through the combination of Internet-of-Things, high-precision geolocation referencing, RFID, LiDAR, Real-Time 3D, machine learning, artificial intelligence and other technologies. Digital twin is claimed to be applicable in virtually any industry and to any object, living being, or system. Not yet available as a product on a massive scale, this imaginary3 technology is being developed and invested in by big tech players, studied and experimented within academic research, put into industry reports by global consultancies, awed, praised and feared in the media.

RT *real time*

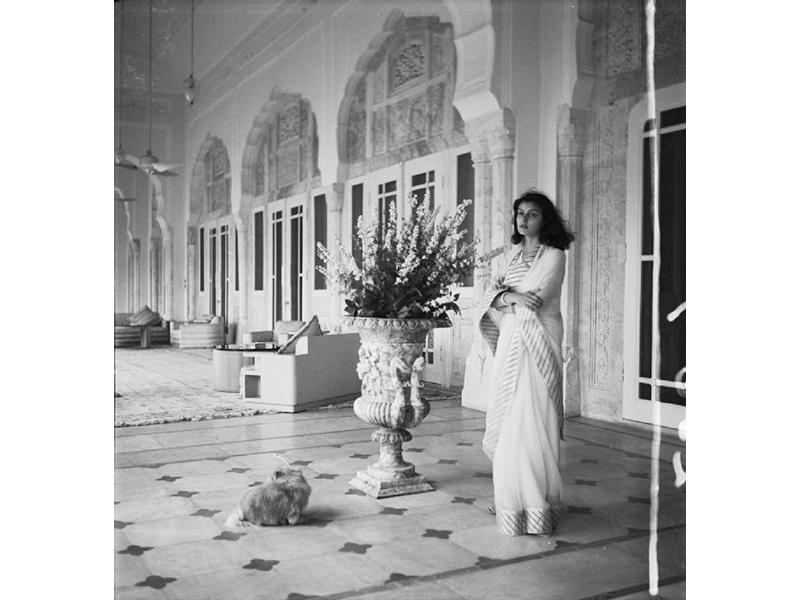

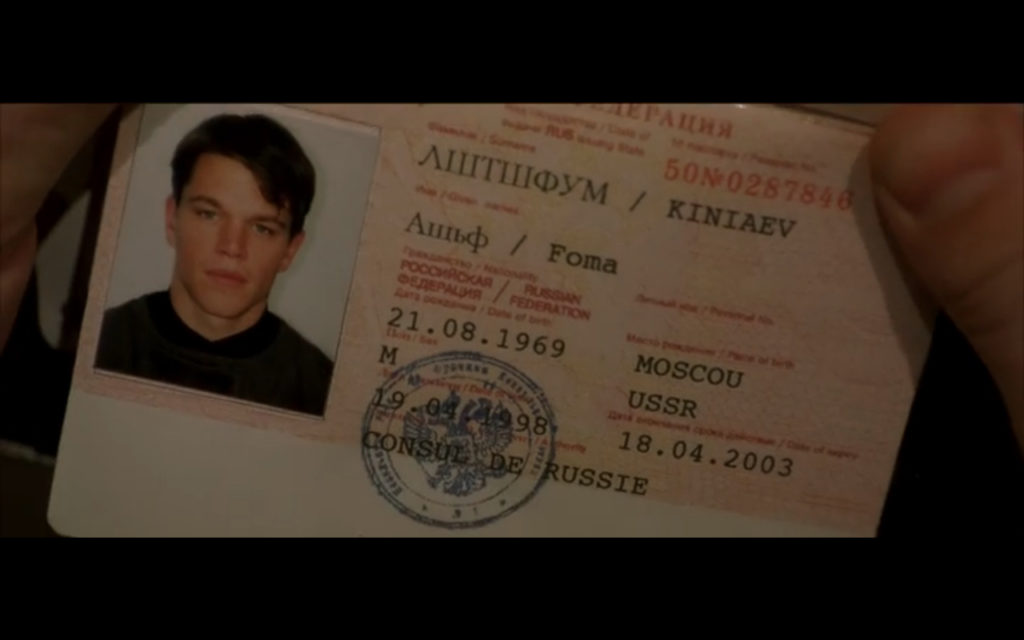

Still from the video-essay in progress

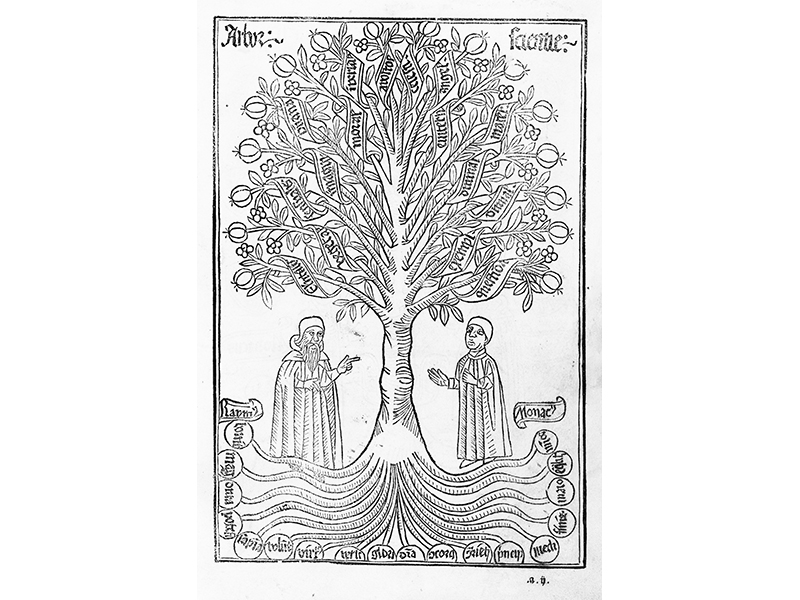

In the context of architectural design, models and simulations have historically worked as design tools, risk management devices, core disciplinary acts, and products. Conventionally preceding the building, drawings (considered as early geometrical simulations), digital or physical models, and other forms of representation had a sequential position within the architecture at least since the Renaissance. Today, with digital twins used in architectural, urban, or other territorial decision making, as well as in research and design, neither the product or the model are ever complete, the iterative design and calibration process between physical and virtual instances virtually never stops.

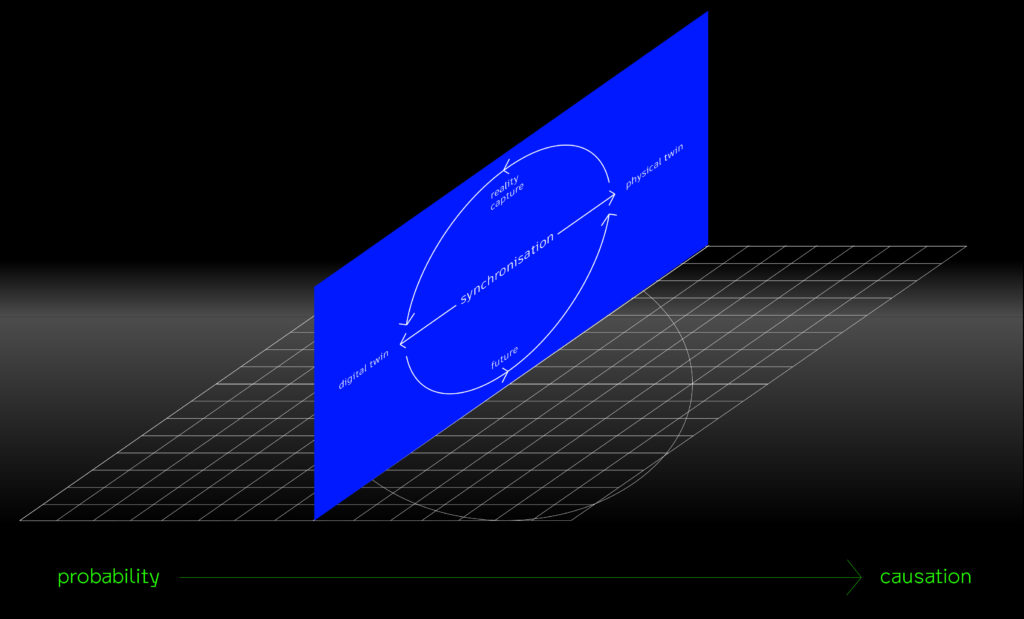

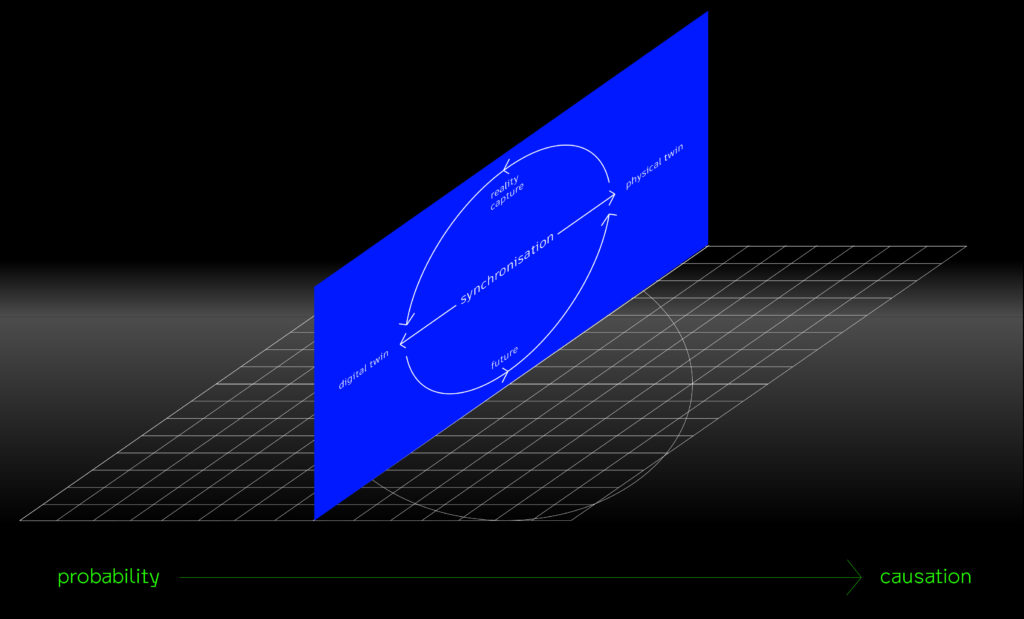

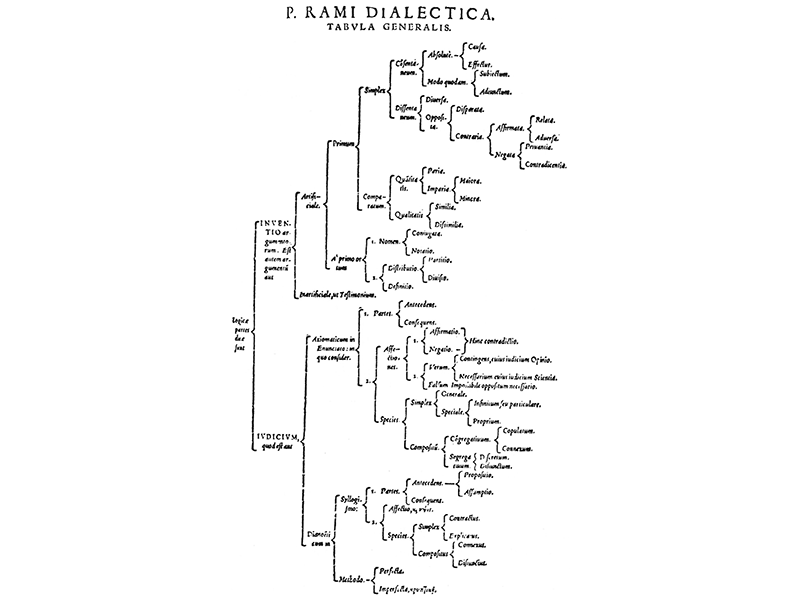

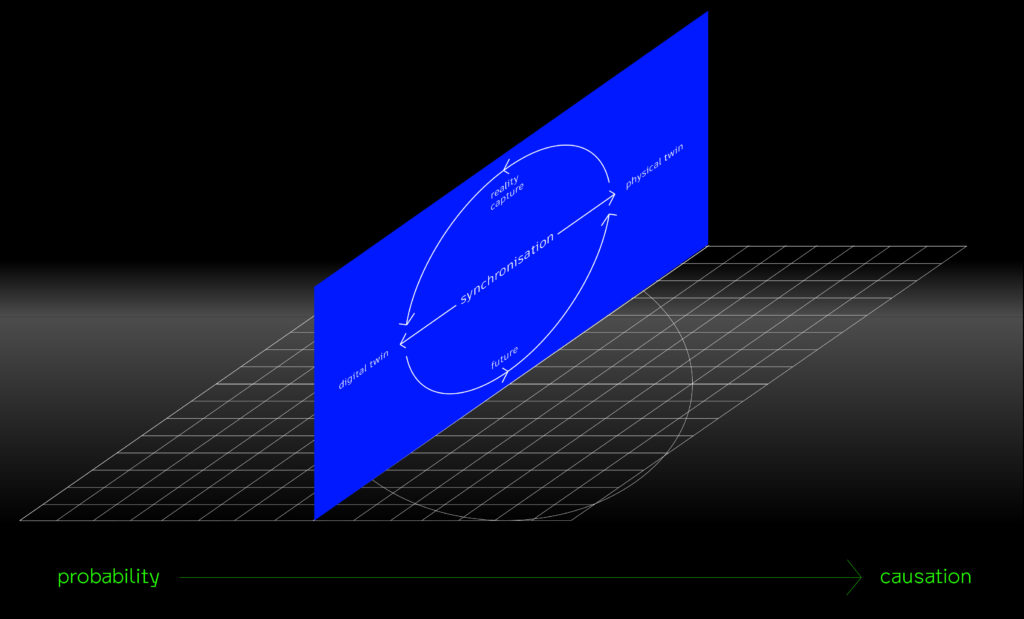

Digital twin amalgamates the design logic of images with predictive computation. Capturing reality and (re) producing it as Euclidean geometry, volumetric data, or a dashboard, digital twin technology continues the legacy of cartesian mapping, Albertian projectional notation, CAD and BIM. In synchronization with their physical counterparts (AKA target systems), digital twins mix – up design, governance and information management. In doing so, digital twin is seen to shift the digital imaging from being notational towards becoming operational, beyond indexical and sequential towards instrumental and synchronous. An instance of a digital twin as a managerial object, changes the status of digital image and spatial data in relationship to the actual space, and produces new forms of temporality and objectivity. Digital twin becomes an operational device for shaping and steering the reality.

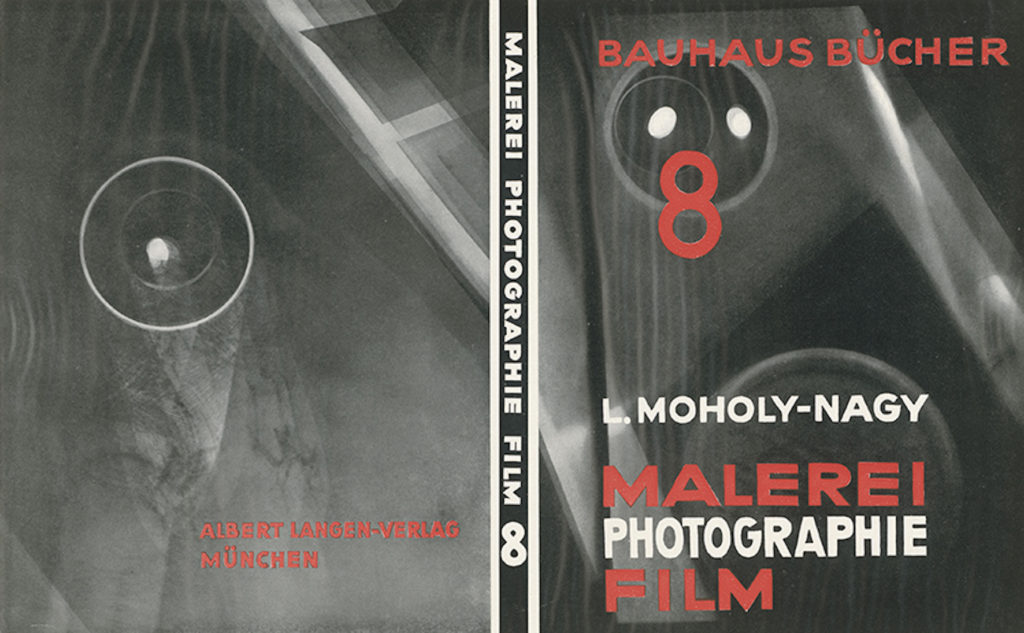

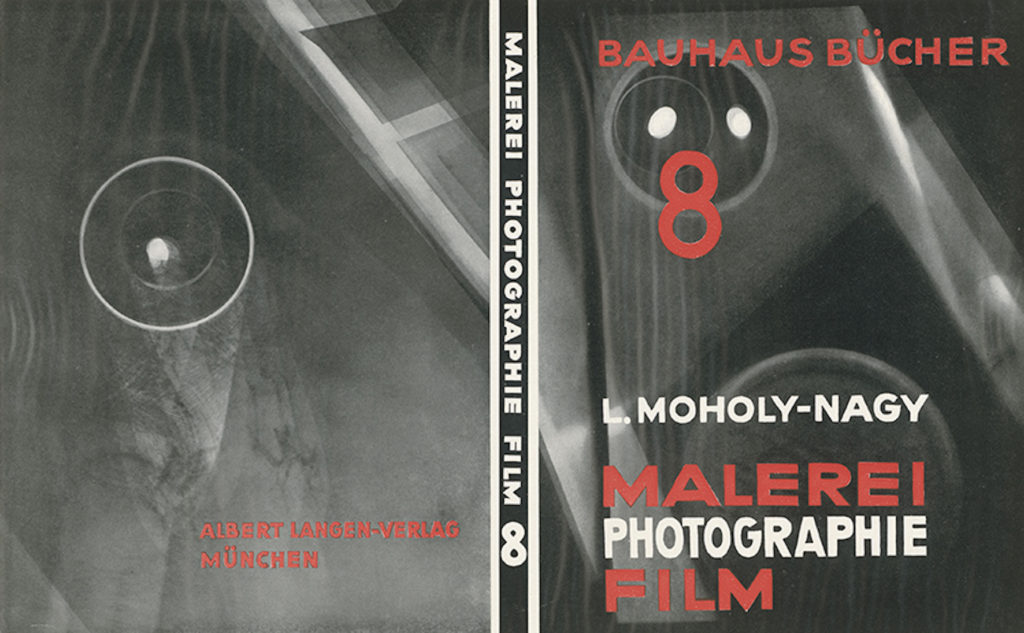

In this regard, digital twins continue the legacy of technologies and techniques that automate visual perception as an instrument to capture and represent information about three-dimensional space, via identification of individual shapes and distances. Lev Manovich calls this way of perception visual nominalism.4 Starting with wooden frames with physical grids, and other kinds of mechanical and optical devices to assist in perspectival painting, today the technologies of automation of visual nominalism are digital tools that capture, record and interpret the information, both visual, and beyond the capacity of human vision.

Fundamentally, the duration of time between information gathering and production of image has become negligible. With the aid of remote sensing devices, information previously inaccessible to human senses, can be tracked and instantaneously delivered and represented in a human-legible. As with photography, where perspectival representations of real objects could be mechanized, now LIDAR scans and digital photogrammetry software enable the capturing of volumetric data that can be converted into a three-dimensional model in a matter of minutes.

Virtual absence of delay between recording (data capture), event (new data occurrence) and the representation of the recording (data displayed on digital twin interface), produces a different kind of temporality, conditioned by the possibility of the inscription of the momentary. To update Bernard Stiegler’s statement on real-time technologies, with digital twins, time has become an interface.5 The time is delocalized and de-realized, as real-time connection between virtual and physical twins both negates the distance and makes the duration negligible. The reality thus is constructed through synchronization, rather than reflection.

Digital twin connects the instantly collected and represented information with its target system. Used for performance simulations, vehicle crash tests, virtual destruction, and any possible experimentation prior to any change in the target system, digital twin becomes the perfected version of its counterpart. As it is updated according to the target system’s changes, so the system adjusts to the digital model. Synchronization, at times, makes either a digital twin or its target system invisible—- as digital twin stops being a static representation, and becomes a “ghost” of the far-flung machine.

-3D- *three dimensional*

In 1998 the vice-president of the US Al Gore created a vision of Digital Earth—- a virtual spinning globe saturated with georeferenced data. The initial vision of Digital Earth was meant to be the planet’s twin, in a sense that it would reflect the changes taking place on a planetary scale — from climate to the built environment and infrastructure. The project would aggregate the data from disparate sources, captured by military and corporate satellites, airplanes, and sensors around the earth. This real-time, interactive replica of the Earth was aimed to become a system of exchange of scientific knowledge and understanding of the planet.

While the Digital Earth imagined by Al Gore was never realized, similar visions came into being with Google Earth, NASA World Wind, Marble and others. Commissioned in 2019 by the EU, project DestinE (Destination Earth) echoes the Digital Earth objectives as it aims to develop a high precision digital replica of the Earth, with simulated human nature and activity, continuously monitoring “the health of the planet” in support of European environmental policies. Combining multiple data resources, DestinE is planned to be used for testing and analysis of scenarios for sustainable development, and to reinforce Europe’s industrial and technological capabilities in simulation, computing, and predictive data analytics.6

Just as the planning of Baroque Ideal cities, Corbusier’s views of the city from the aeroplane, military perspective or planar projections, the way the world is revealed through a digital means of three-dimensional simulation, exemplify particular legibility regimes as primary tools for production of knowledge and control. Whereas, as argued by Erwin Panofsky7, perspective (perspectival projection) has been a “symbolic form” that linked social, cultural and technical practices in the West, and formed the particular vision of the world, so the digital twin, combining volumetric 3D and a corresponding data-base8, could forge a particular worldview. Today, as 3D simulation has largely replaced projectional representation, and as more and more everyday interactions with reality involve the “spinning” of the digital content — from Pokemon Go, navigating through Google Maps, spinning Rhino models, to the virtual tours on Houzz.com, the moving, navigable and three-dimensional digital space overlayed with dynamic information from a corresponding database are exemplary of the contemporary legibility regime. Jordan Crandall calls this type of (re)presentation “operational media”9: representations of events overlayed with floating monitors, calculated distances, graphs and other. These overlays filter, tag and sort the mediated reality beyond visual nominalism.

Mario Carpo writes that with the development of the new volumetric capture technologies, “knowledge now can be recorded and transmitted in a new spatial format”.10 The amount of volumetric data captured by tech companies, planning agencies, military and police bodies is increasing both in scale and resolution. William Mitchell in The Reconfigured Eye noted the striking similarity between linear perspective and CGI (Computer-Generated Imagery), as a medium that, unlike photography, does not sample reality, but produces its own virtual worlds.11 Seen as a quest for accuracy and exactitude, or for so-called photo-realism, virtual worlds are often created and imbued with scale, dimension and texture as life-like as possible. The 3D volumetric data for digital twins, captured with Lidar or photogrammetry, is made legible using software with opaque data-processing algorithms, polished with additional 3D simulation and visualization. Samples of reality, in the form of volumetric data are utilized as raw material to produce the new reality of digital twin, similarly to virtual worlds of the entertainment industry.

DT *digital twin*

The Centre for Digital Built Britain is working on a so-called National Digital Twin — an ecosystem of connected digital twins across the United Kingdom. The vision for the national digital twin is not that it will be a huge singular twin, replicating the shape and geography of Great Britain, but more of a topological networked federation of digital twins, connected through shared data. Here the design is equated with information management at the scale of the nation-state, and the quality, value and profit of a remote asset are made visible through its digital replica. The direct relationship between the space, and those who design, develop, build, use and manage it, is further mediated via digital twin. Digital twin streamlines, directs and orchestrates the relationships between the stakeholders that have access to it.

Building Information Modeling, a predecessor of digital twin technology, enables participation of different agents in the design processes. Yet participation in BIM design, while allowing for negotiation and consensus among the architects, engineers and consultants is by invitation only, whereas Gemini Principles, for example, advocate for open source digital twins.

Furthermore, the data that comprises a digital twin as a holistic entity typically originates from heterogeneous sources, which need to be correlated and confirmed; sensors, tools and systems that capture and transmit data utilize different formats that have to be re-encoded and translated into a cohesive whole. A large-scale standardization system that would enable broader digital twin interoperability and integration has yet to be devised, and is currently available as a set of proprietary solutions.

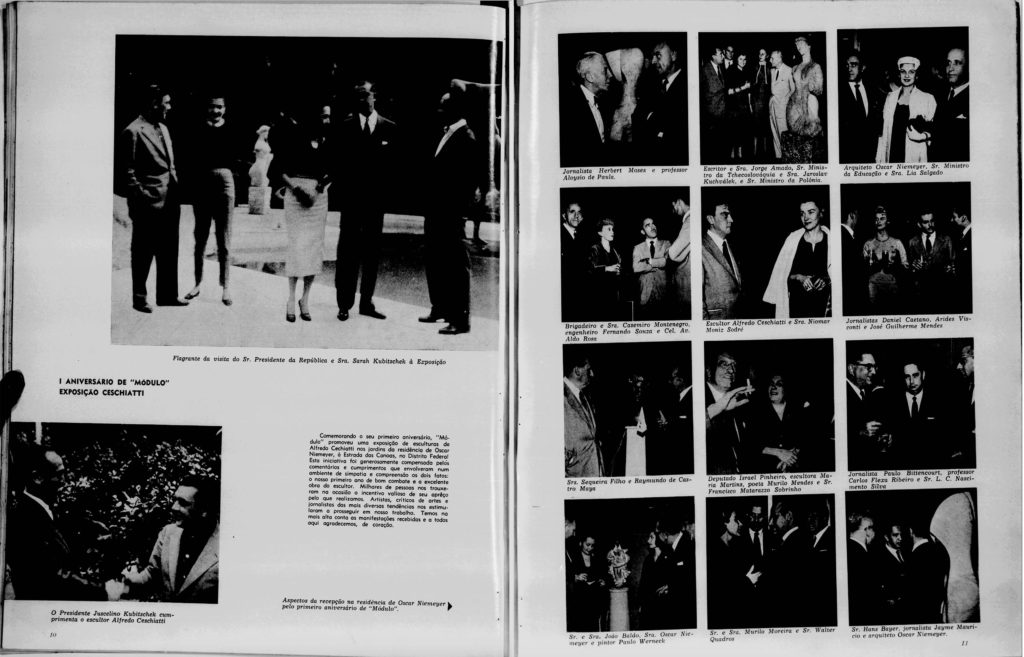

Still from the video-essay in progress. Image credits: Left: Prototype of the “mail box”constructed at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) to remove carbon dioxide from the Apollo 13 Command Module (CM) is displayed in the Mission Control Center (MCC). Image Credit: NASA. Right: This view of the damaged Apollo 13 service module. Image Credit: NASA

As with any software which is aimed to “to organize the world’s information” and make it legible and useful, digital twin does implicitly organize the world itself,12 not unlike architectural notational systems that translate certain values and ideas into a particular spatial layout. As Benjamin Bratton wrote, images are a specific genre of machines, digital twins can be seen in the similar perspective.13 Directly affecting the systems it represents, digital twins are not only providing semiotically and instrumentally convincing and legible diagrams of distant objects and processes, they actually do what they represent. It then becomes an aperture through which both algorithms and the users retrace the world.

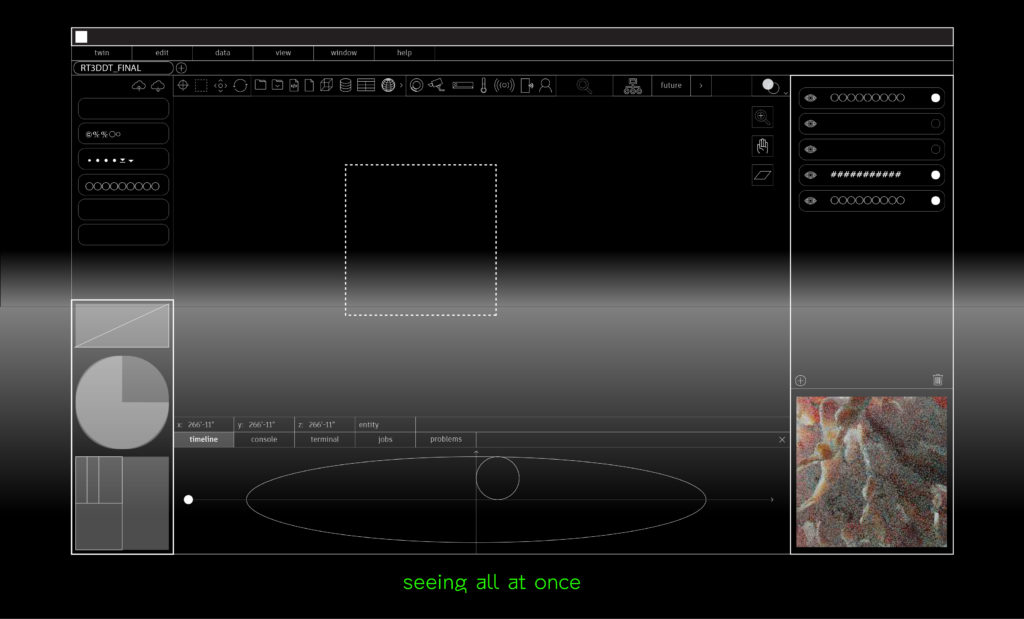

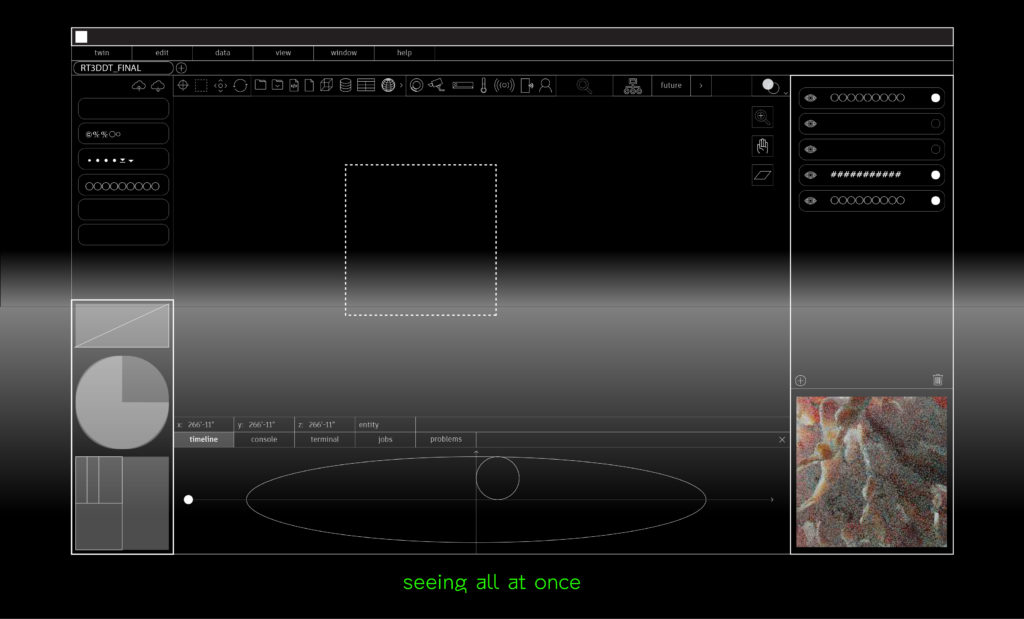

The technologies that make digital twin possible and the concepts they entail have developed in part due to a particular paradigm of the world, one that sees space as Euclidean geometry, emphasizes exactitude and discreteness of objects in space, and confuses seeing and knowledge, production and reproduction, spectacle and recording. The graphic user interfaces of existing prototypes of digital twin platforms, such as Microsoft’s Azure Digital Twins, Cityzenith’s SmartWorldPro or XMPRO’s solutions are a peculiar amalgamation of the familiar parts of a code editor, 3D modeling software, business communication app and a cockpit. Combining heterogeneous interface semiotics, and a wide array of technologies, digital twin, however, seems to be virtually indifferent to what kind of entity is its actual counterpart. It virtually equates a city to a factory floor, to a house, to a person, and perhaps, makes everything a subject for optimization and re-calibration.

With its aesthetics equated to the operationality, the anticipatory logic of digital twin makes things and relationships appear, and produces new kinds of spaces for action and speculation. Ultimately, digital twins contribute to a legibility regime in which images and spaces are updated in real-time, enhanced through digital processing and filters, overlaid with numeric, non-visual or other types of data, implying (inter)action and a capacity to respond. As with mapping, ballistics and surveying techniques in Baroque era co-constructed ideal cities, so airplane photography pushed the limits of modernist urban planning, and social media currently engenders global architectural styles and travel destinations, digital twin technology is prone to generate new type of space and reality. While it is not yet available and ubiquitous, dozens of companies, big tech players and regional startups are building solutions at the moment. For now, digital twin is surfing waves of hype, discussed and speculated upon. Joining the discussion with a more critical lens, this essay aims to unpack some of the aspects of digital twin and its capacities to digitally (re)produce the world.

Still from the video-essay in progress

1 At the moment, there are multiple definitions of the term, I provide the generalized version. For more see David Jones et al., “Characterising the Digital Twin: A Systematic Literature Review,” CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology 29 (May 2020): 36–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. cirpj.2020.02.002.

2 Lee Mohon, “Apollo 13: The Successful Failure,” Text, NASA, April 6, 2020, https:// www.nasa.gov/centers/marshall/history/apollo/apollo13/ index.html.

3 While digital twin technology is not readily available as a consumer product or a clear and scalable industry solution, it is discussed and speculated upon. Many traits of the emerging technology are described in the media, yet not so much visual depiction of it or recording of how it works iis shown except marketing material.

4 David Gelernter, Mirror Worlds or the Day Software Puts of the Universe in a Shoebox: How It Will Happen and What It Will Mean (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

5 Stiegler refers Paul Virilio to suggest that real time technologies turn the duration of time into a ‘writing surface’, Bernard Stiegler, Technics and Time 2: Disorientation (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2009), 124

6 “Destination Earth (DestinE),” Text, Shaping Europe’s digital future – European Commission, August 18, 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/destination-earth-destine.

7 Erwin Panofsky, Perspective as symbolic form (New York: Zone, 1997).

8 Lev Manovich, “Database as Symbolic Form,” Convergence 5, no. 2 (June 1, 1999): 80–99,

https://doi.org/10.1177/135485659900500206.

9 Jordan Crandall, “Operational Media”, CTHEORY, (2005)

10 Mario Carpo, The Second Digital Turn: Design beyond Intelligence, 2017.

11 William J Mitchell, The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2001),134

12 Here I am paraphrasing Google’s famous corporate mission statement: “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.”

13 Benjamin H Bratton, The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2016), 219-250

Alina Nazmeeva is a Russian architect and researcher, investigating the relationship between digital images and social spaces produced by them, interfaces and publics, digital twins and videogames.

Alina is a graduate of Master of Science in Urbanism, MIT; and a former fellow of the New Normal program at Strelka Institute of Media Architecture and Design. She is a research associate at future urban collectives lab at MIT, where she works on design of spaces and platforms for new forms of collectivity, and a research analyst at MIT Real Estate Innovation Lab where she focuses her research on understanding the economy and design of virtual worlds and online games. Her writing has been published in PLAT Journal and Media-N.