Editorial

Cartha

Confrère: “ fellow member of a profession” How do architects relate to each other nowadays? Before trying to address this question it is pertinent to make a clarification, to distinguish between ways of relations and ways of communication. Although they inform each other, they are not necessarily the same. The relation amongst architects is a […]

Confrère: “ fellow member of a profession”

How do architects relate to each other nowadays? Before trying to address this question it is pertinent to make a clarification, to distinguish between ways of relations and ways of communication. Although they inform each other, they are not necessarily the same. The relation amongst architects is a very intriguing and inclusive map of these three elements, architectural representations, balance between “I” and “We” and time.

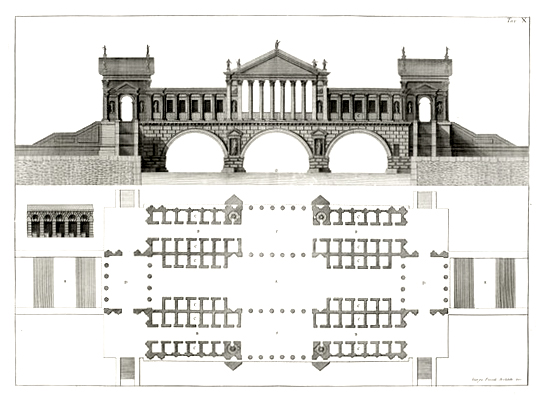

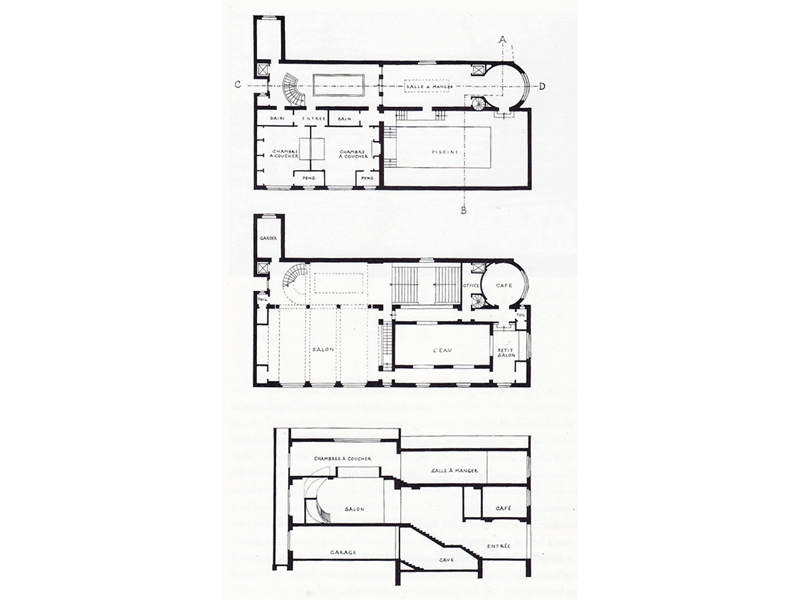

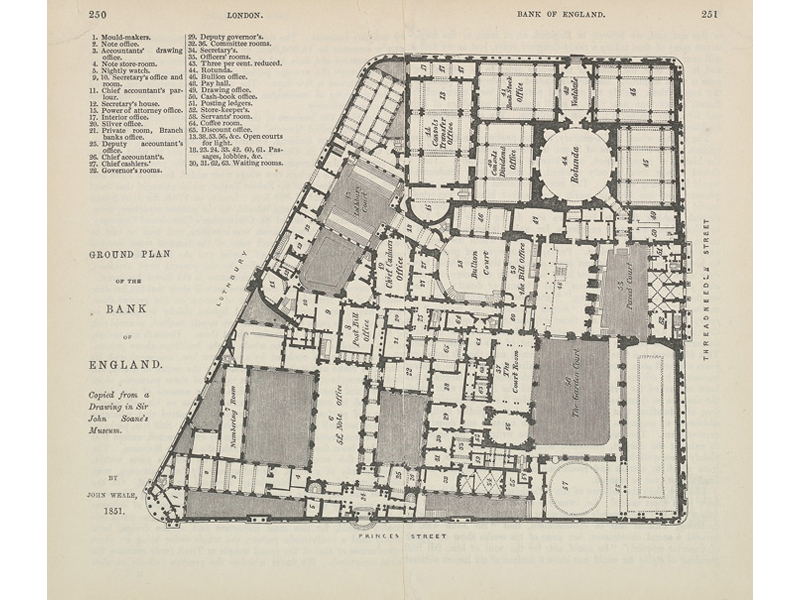

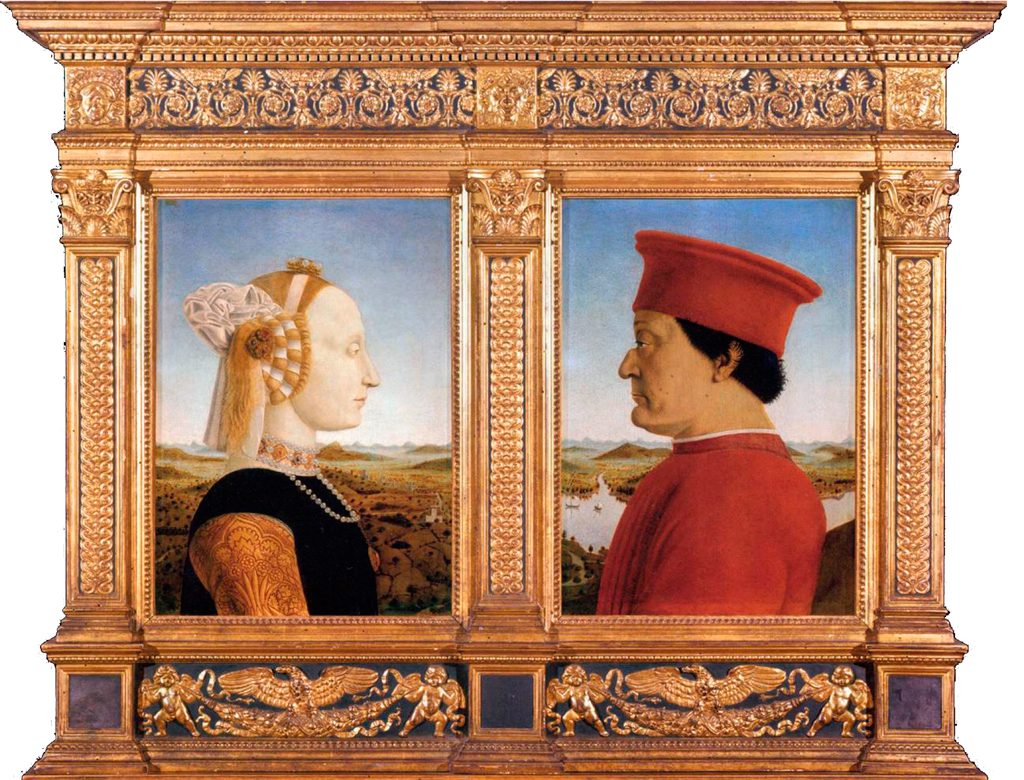

In this sense, when we talk about ways of communication, we are referring to ways of experimenting architecture. Hence, we could say that the only impartial way of doing this is by visiting buildings and cities. Contrarily, partial ways of experimentation are representational media such as texts, drawings, floor plans, sections, elevations, perspectives, renders, images, as well as representations of built architecture such as photography or video. All these ways of communication share a partial or edited view by the person who produces them.

What are the types of relation amongst colleagues? Historically, we could mention a number of professional relationships: the master-apprentice, and so the evolution in complexity of this structure over time, but that nevertheless finds its reason in the transmission of knowledge within a more or less hierarchical decision-making system; the arena of the public competitions and public and published debates; schools; professional associations and manifestos or groups.

However, what is of the upmost relevance is that these ways of relations or any other are governed by the timeless fight of the binomial “I” vs. “We” or creator-author vs. group-collaboration.

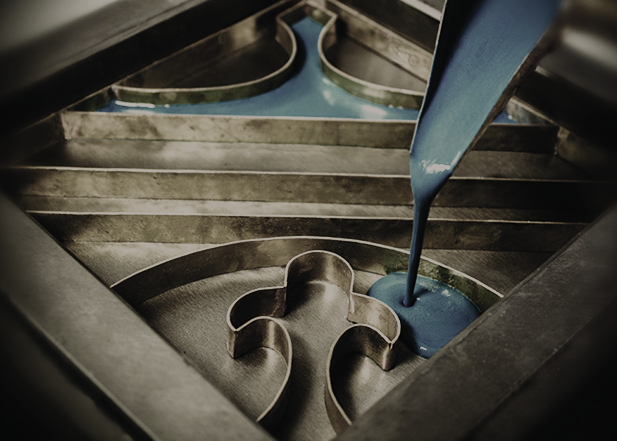

Our time allows for unconscious or non-orchestra- ted relations globally nurtured by the increase of exposure to architectural representations and designs and the consequent impact on projects of architects often geographically and culturally distant. Accordingly, communications and travel means also allow for collaborations no longer based on territorial strings. This advises for a revision of the figure of the journeyman. Nowadays, we are all involved in an intensified and perpetuated journeyman state.

Competitions: as with all other service providers inserted in the capitalist system, architects have two paths they can choose from when approaching the acquisition of a job: present a better quality or present a cheaper price than their competitors. The quality is not always clear, it remains, from a certain point on, open to interpretation. Prices are numbers and, as such, easy to compare.

This apparently democratic system of acquiring/ appointing a job, through an open competition, can push up the general quality of architecture and allow young architects to fence with established ones on a neutral ground but, on the other hand, it can also create situations of precarity when the prices to pay for the services architects provide sink, in a desperate struggle for assuring “work”. In which situation do we find ourselves in?

School and professional associations: it would be pertinent to ask whether they are carrying out their labour of being platforms for communication and exchange amongst architects and towards society for the dissemination of architectural knowledge. We could question if the number and size of schools in each country truly allow those goals. Are these institutions failing or not at supporting the profession?

Manifestos: do they make sense nowadays? Are they coming up to the frontline? This is the cyclic connotation of Time. Will we soon witness a revival of manifestos? Or maybe they never really left us.

Where is the focus in the binomial “I” vs “we”? Is it the current relations amongst architects more affected by the idea of collaboration and of a social agenda? Is the focus coming back to the “we” to a broader social- politic dimension of architecture?

2008-2015, we could list Madrid, London, New York, Hong Kong, Arab Spring; the beats of these manifestations keep resonating. The precariousness in the profession due to the failing balance between the number of architects and the size of the market, as well as to the non solved adaption of architecture to new professional scenarios where the architect has very limited control over the cities and the construction processes, is silently eroding the professional panorama in no so few countries.

2015, we are at the dawn of a new time and we have just witnessed the decline of an era characterised by the celebration of excess at different extends. On the one hand, the excess on construction, with a dramatic impact on the number of built properties, the housing market collapse, and the territory; on the other hand, the excessive celebration of the “I” that gave origin to the late 20th century architectural star system and marked a period. Nowadays, it seems that it is not the way to go. This phenomenon was in part the reverse of large public expenditures in iconic buildings that no longer enjoy the acceptance of citizens. In addition, ecological concerns are growing every second. Ecology understood as something collective, social and energetically efficient. The new generations, and by new generation we mean practicing architects regardless their age, are affected by an increase awareness of this conception of community.

We believe this is the global scenario that conscious or unconsciously informs the experiences of our contributors. Indeed, such a perfect cocktail results, as stated, not only in a major awareness of ecological and collective issues but also in a greater interest on collaboration as a strategy to face a challenging time.