Foreword

The image of Rome narrated by a distracted traveler at the beginning of the XIX century or the image absorbed by the thousands of tourists that every day invade the city has remained substantially the same. In the collective imaginary, Rome is always itself: The Eternal City.

But can this image represent the true nature of the city and above all that of contemporary Rome? Would it be possible to find a new mental image able to represent the entire city and its complexity?

Borderline metropolis [1] is an attempt to answer those questions and at the same time is an investigation of the territory of Rome as well as a study that offers a different interpretation of the contemporary city.

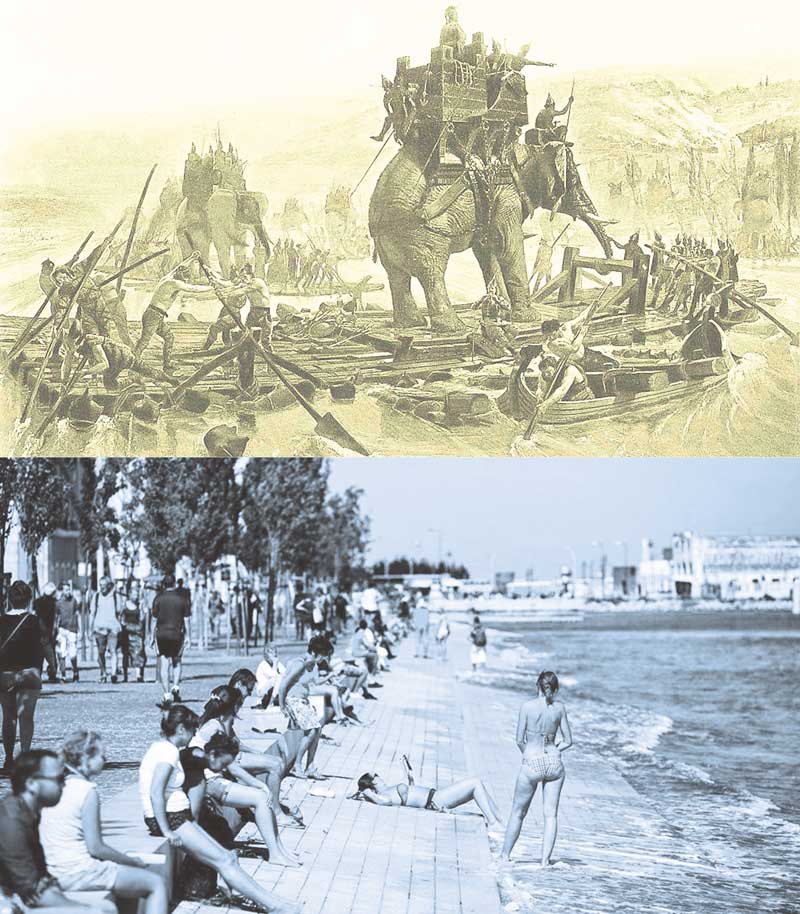

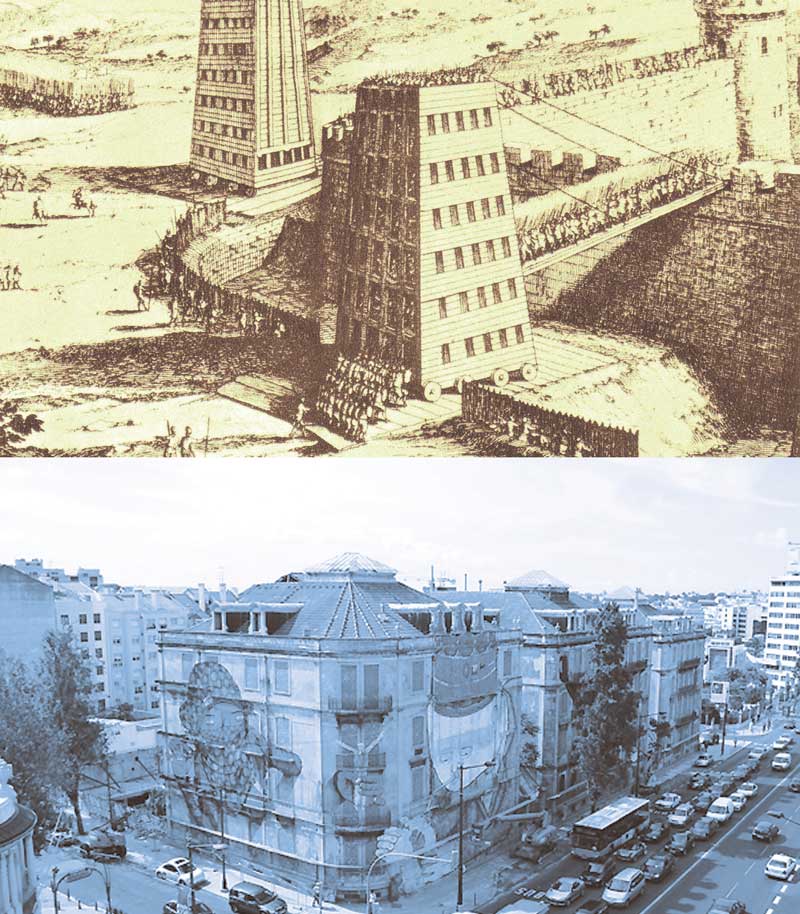

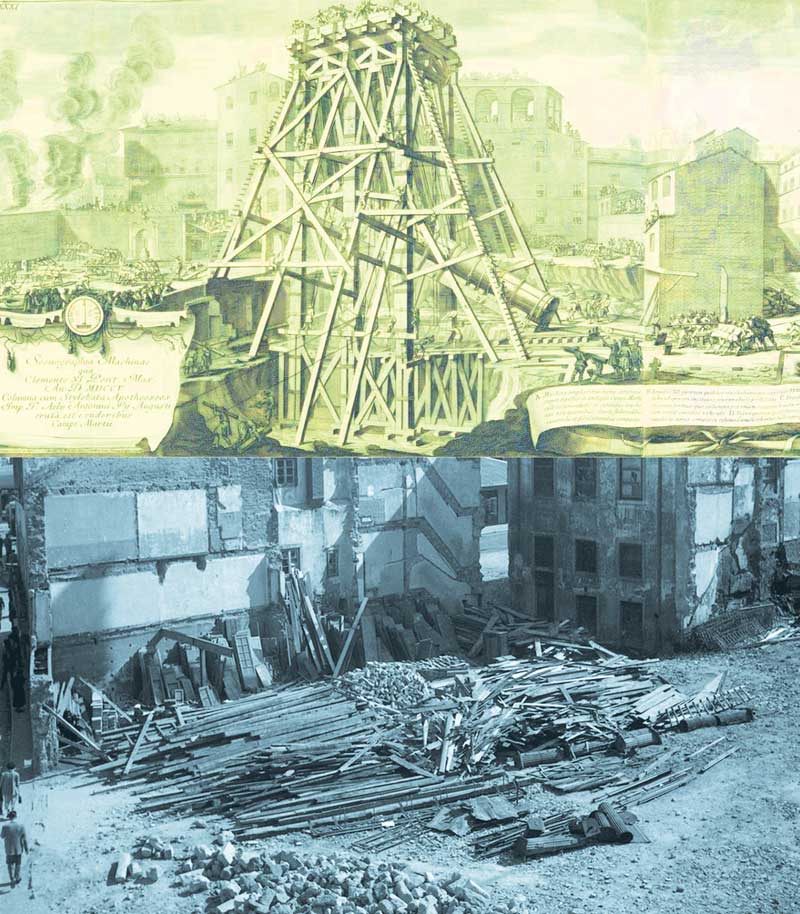

Paolo Canevari, Colosseo, 2000 (Marco Andreini)

Martin Parr, Roma, 2006 (Magnum/Contrasto)

Phenomenology of a City – A view from inside

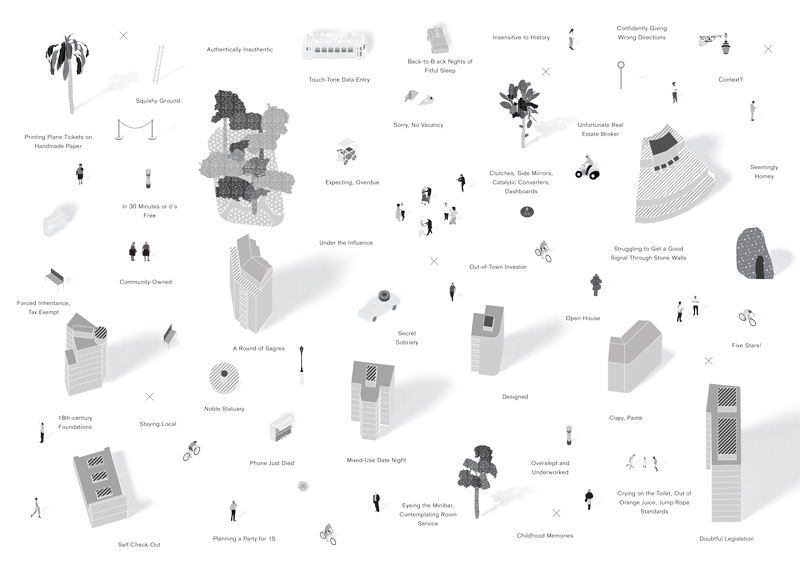

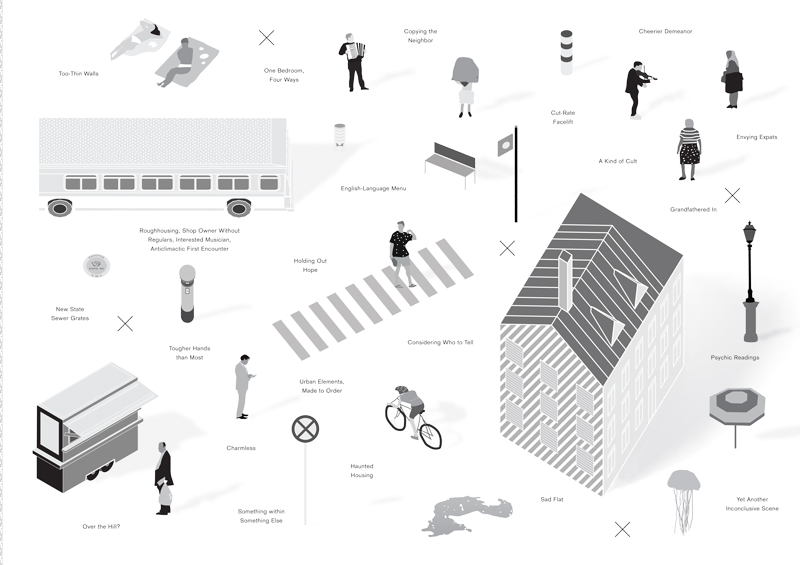

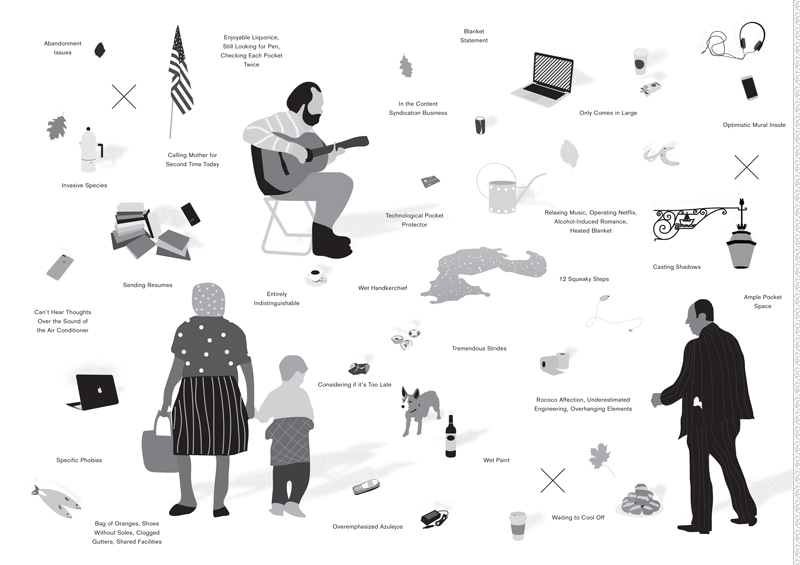

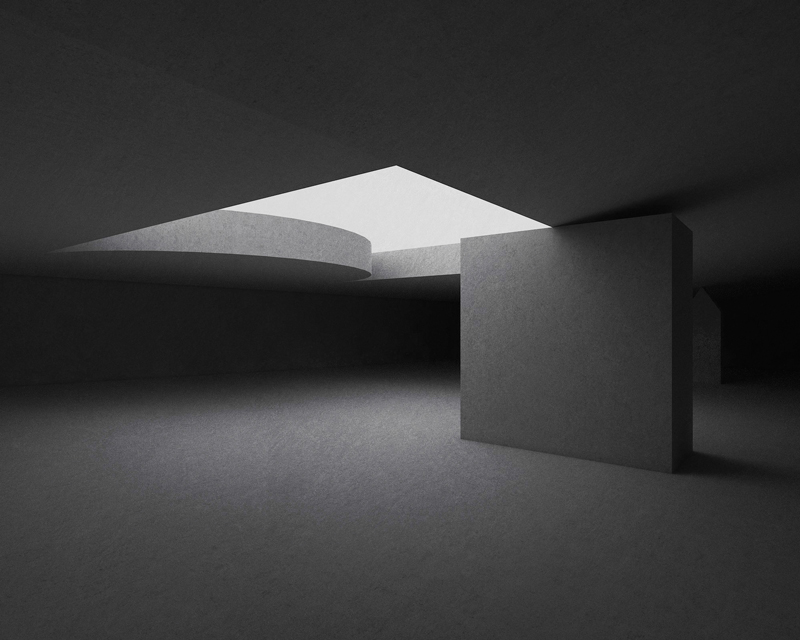

The investigation began with a true urban phenomenology, with a bottom-up survey of the territory. A purely visual narration assembled in the everyday experience of crossing the city, from the center to the outskirts, taking unusual itineraries.

Walking through borderlines, thresholds, places of transition, empty zones and varied textures, scraps of countryside, densely edified areas, we discovered an infinite variety of incongruent features capable of generating moments of surprise and astonishment, straddling the picturesque and the sublime. We basically found ourselves crossing a multiplicity of places of transition, places between interior and exterior, between center and periphery, between city and country, places that have an inner instability.

The act of crossing the city brought us to a new image of Rome, or perhaps the same image that has fed the fantasy and creativity of many contemporary artists [2]; an image very distant from the sequence of monuments and places that forms the established imaginary of the Eternal City.

While the condition of instability in urban studies is often associated to a negative image and today’s global cities pursue the idea of a perfect, reassuring stability, Rome then is different and if its mutable, open, unexpected instability is interpreted not as a problem but as a potential condition [3] Rome might offer a stimulus to construct an alternative to the standardizing and generic dimensions of the contemporary city, starting with instability as a condition capable of including openness, vitality, creativity and authenticity, overturning the established equation of stability = security = well-being.

Labics, Roma

Labics, Roma

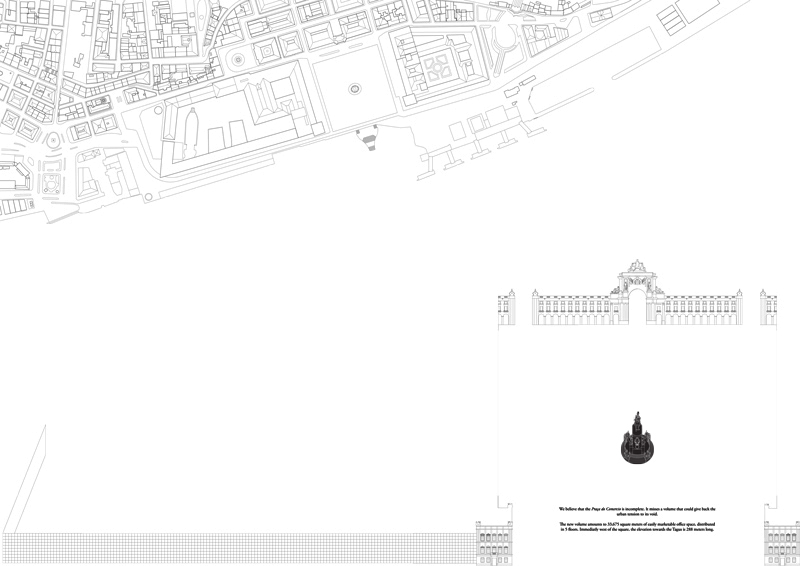

City Form – Views from the top

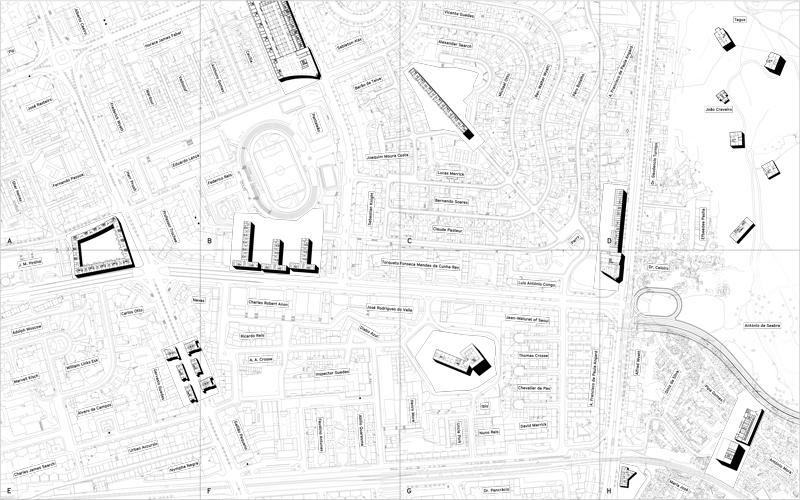

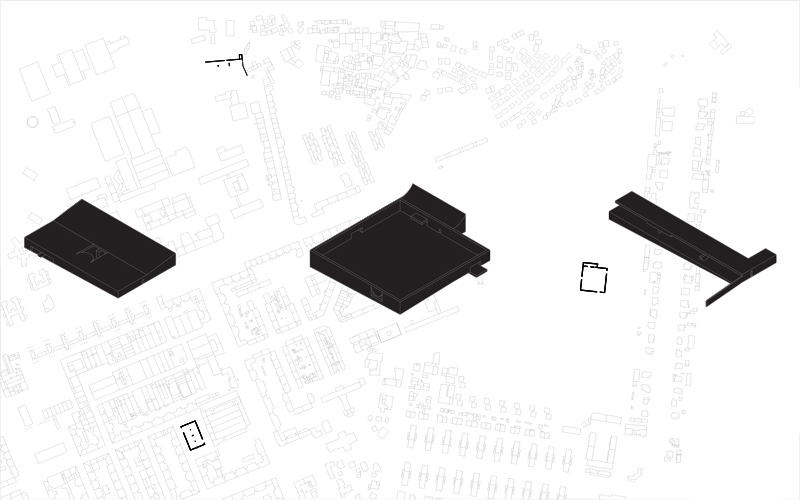

Alongside the investigation from below, the city has been analyzed from above, to understand possible relations between its Form – the physical condition – and the instability of its perception.

Considering Rome, like any other city, as an evolutionary organism, the research has mainly focused on the structural elements which have guided the transformation of its territory during a long formative process [4]. Convinced that not only the present form, but also any potential configuration the city can assume – what Sanford Kwinter calls the “embedded forms” [5] – is inscribed in those evolutionary mechanisms.

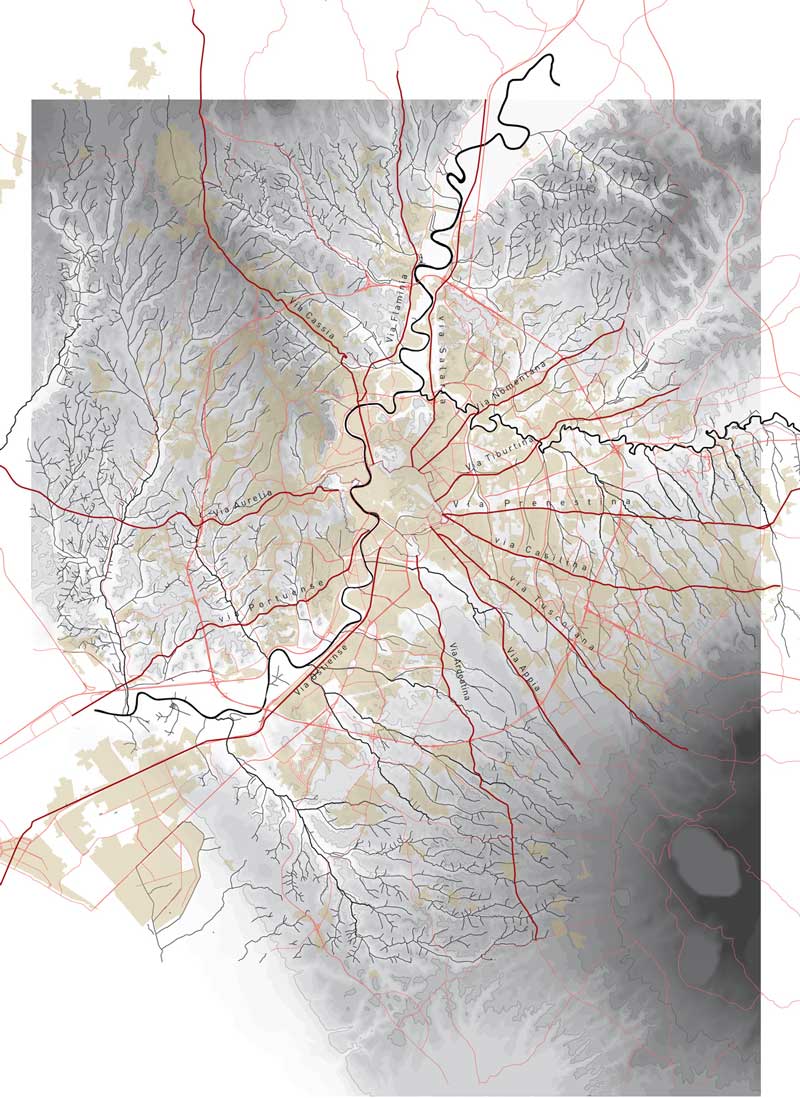

Redrawing the city through several maps we discovered that a few but consistent elements drove the transformation of its territory over centuries: the landscape, with its symbolic power and physical constraints – topography, water, morphology – and the radial structure of the Roman consular road, the real political form. No major planning process, nor strong external rules, Rome followed a kind of natural growing process (the speculative forces followed the same natural pattern).

The result is that of a territory substantially characterized by two closely connected phenomena:

an urban structure organized in islands, each in turn different in fabric, density and typologies;

the presence of a complex, articulated constellation of voids – which as a whole represent over 70% of the urban territory of 129,000 hectares – ranging from small natural spaces to the large green islands of the Ager Romanus [6].

This is why the actual Rome over time has always been interpreted along two Form-Manifestos: on one side that of the Archipelago [7], which is about built islands in a continuous un-built natural space, on the other side that of a great Piranesian Campo Marzio [8] of 2.700.000 inhabitants [9], which is about incoherent built islands one next to the other. Both images are in a way similar, based on an additive logic of incoherent pieces – which is part of the DNA of the city.

But is this the only possible image? Can we find a new image for the city, which is coherent with its genealogy and its actual form? Able to incorporate the immateriality and the openness of the unstable condition but at the same time able to activate, connect, and reinforce most of the recent urban islands disconnected from the rest of the city?

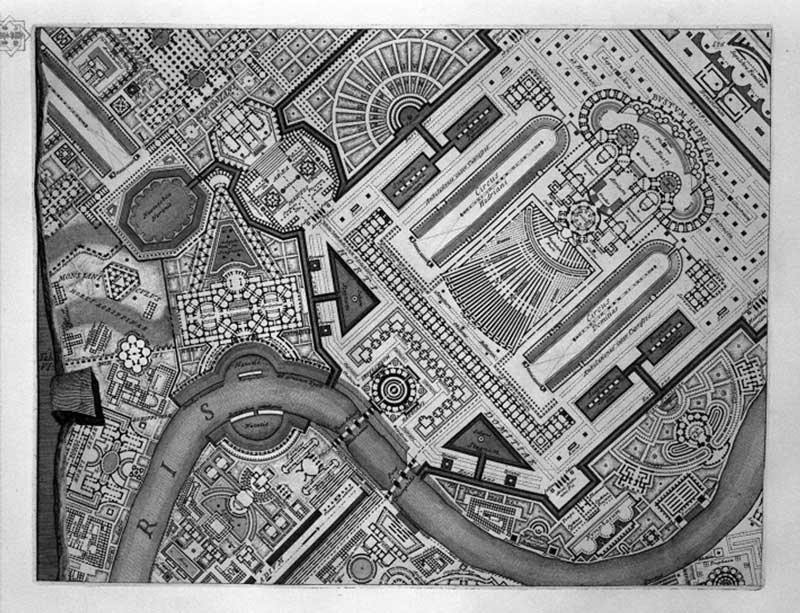

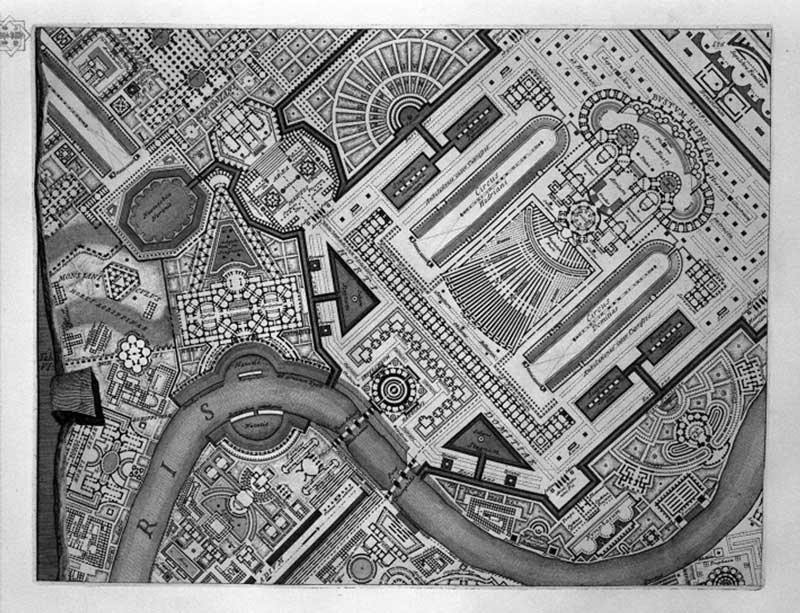

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Ichonographia of the Campo Marzio, 1762

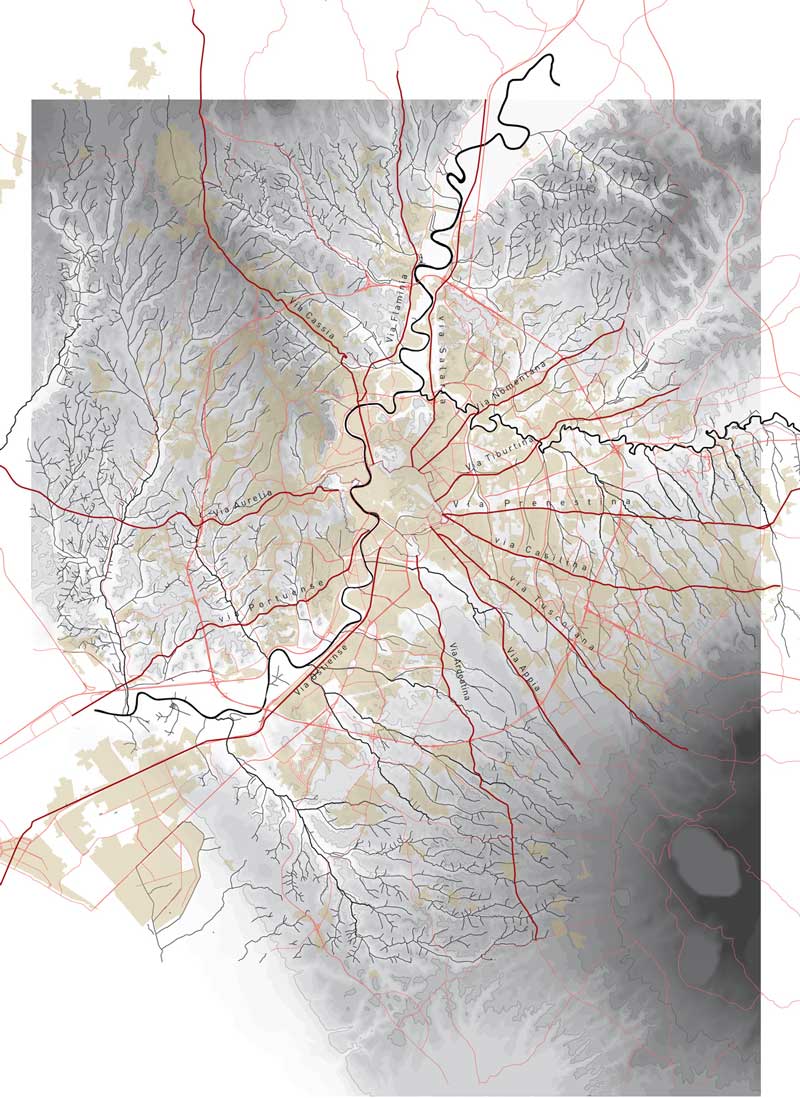

Labics, Topography / Hydrography / Roman consular system / Contemporary structures and city

An emerging structure for Rome – The network of the borders

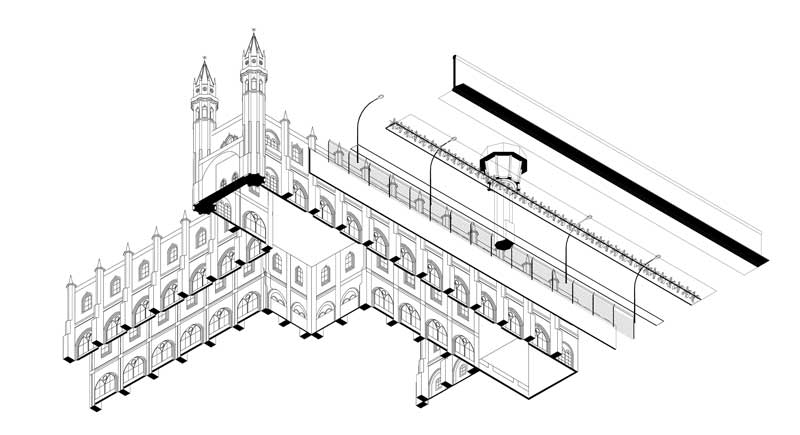

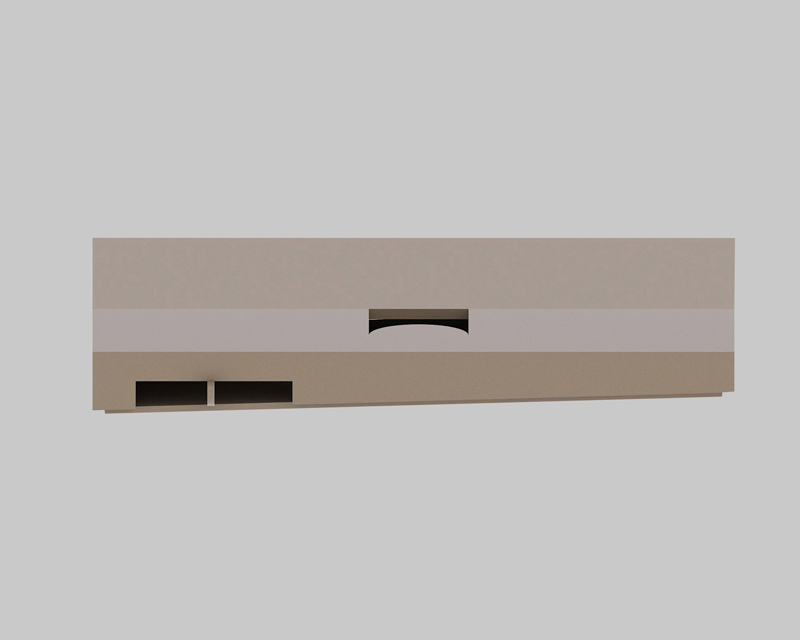

The present Form of the city of Rome probably allows a different and more fertile interpretation than the one of Archipelago or Campo Marzio: the formal structure in islands, by nature, multiplies the edge condition with its true variegated set of material and immaterial features. This borderline condition can be seen as a phenomenon of “retroactive” consciousness of a strong structural presence that has not yet taken on either a clear organization or the necessary awareness within the metropolitan territory. The system of edges could become, if made explicit, a new structural pattern for the growth and development of the city, capable of connecting centers and outskirts, full and empty zones, different city portions, while being a tool to gain renewed aesthetic awareness of the cityscape.

Borderline Metropolis develops an hypothesis according to which the existing system of edges can be interpreted as an active tool for the transformation of the city. A network that is able to react, and consequently change the quality of the border, in the areas where the city is weaker. In the case of Rome, for example, where is revealed a lack of density or connectivity, or where is prevailing a mono functional character of neighborhood or the spatial qualities of the cityscape are extremely poor. The activation of the borderlines could thus become the driving force for the renewal of entire urban areas [10] and reinforce the public character of the city: Borderline Metropolis in fact combines in-depth analysis of the metropolitan territory with the definition of methods and tools to reactivate the borders, transforming the disconnected voids, reconnecting the inactive parts of the city, treating the territory as a whole and thus permitting a differentiated form of organization of the metropolitan territory.

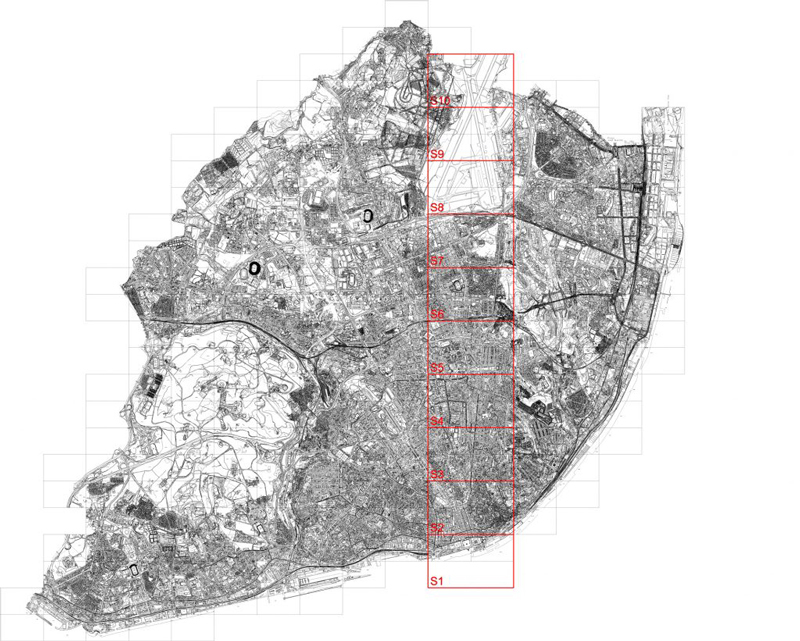

Labics, The islands and the emerging structure, Roma

Labics, The structure of borders, Roma

Learning from Rome

Can the Borderline Metropolis be interpreted as a model for the transformation of other cities? Can Rome be seen as an antidote against the generic aspects of global cities?

The form of the city in itself can be considered as a model in its own right: a discontinuous city composed of an infinite series of different ecologies, whose perfect imbalance determines a unique urban territory rich in variety and differences.

But Borderline Metropolis goes beyond that: it advances an idea of the city and a model for its transformation at the same time. It proposes an organization that goes beyond the closed form of traditional planning and the idea of the city made of stable centers and defined city fabric. Borderline Metropolis moves towards an open, reticular, flexible conception of the city, able to respond to the needs of the territory and its inhabitants in a local and at the same time general way. The system of edges is thus a new infrastructure that can be activated and manipulated according to the needs. As a model, the network is a tool that differs from those normally used in urban planning, because it is constantly capable of updating and modifying itself based on changes in the urban fabric and knowledge regarding the complexity of processes of transformation. [11]

Finally, Borderline Metropolis does not give up on the necessity of a symbolic form behind the project of the city and, at the same time, it does not surrender to the free market approach of laissez-faire, or to the ideological approach of the bottom-up planning as a recipe to the progressive city gentrification. Borderline Metropolis does not impose an a priori form but defines the structure of the form: the idea of the network is the one of an open evolutionary form that transforms itself like an organism, and that is capable to melt values of diversity and creativity together with a structured urban system.

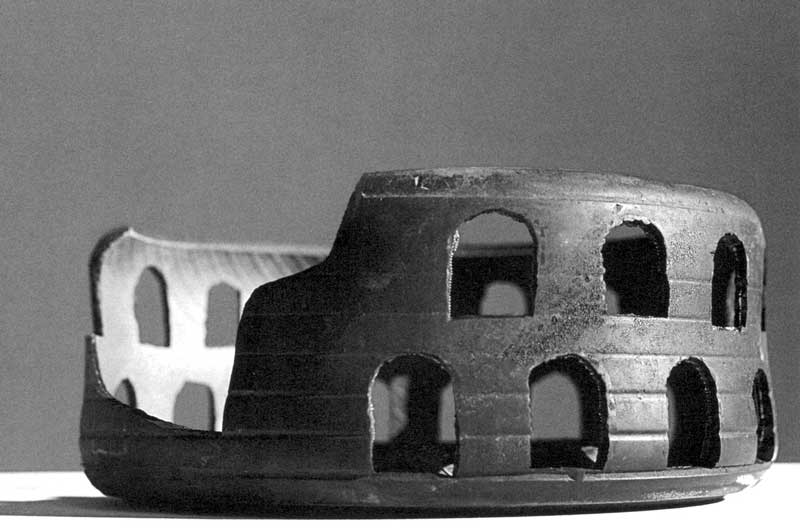

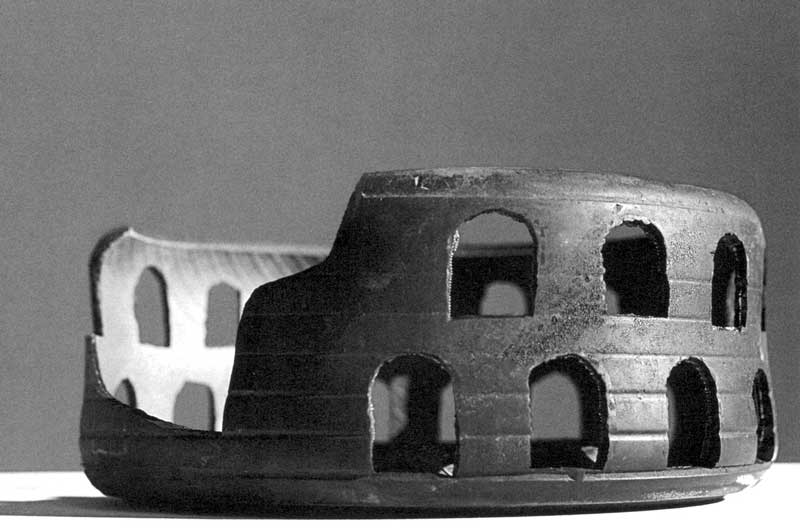

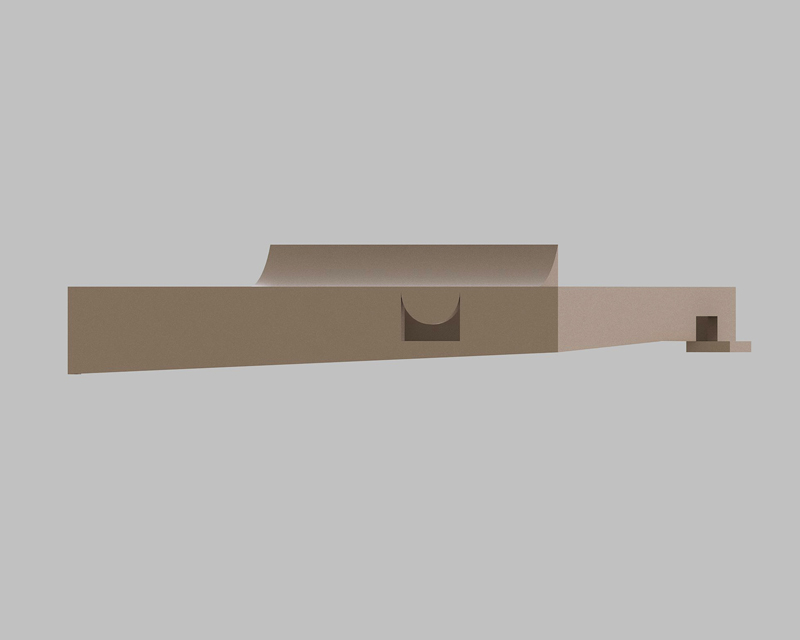

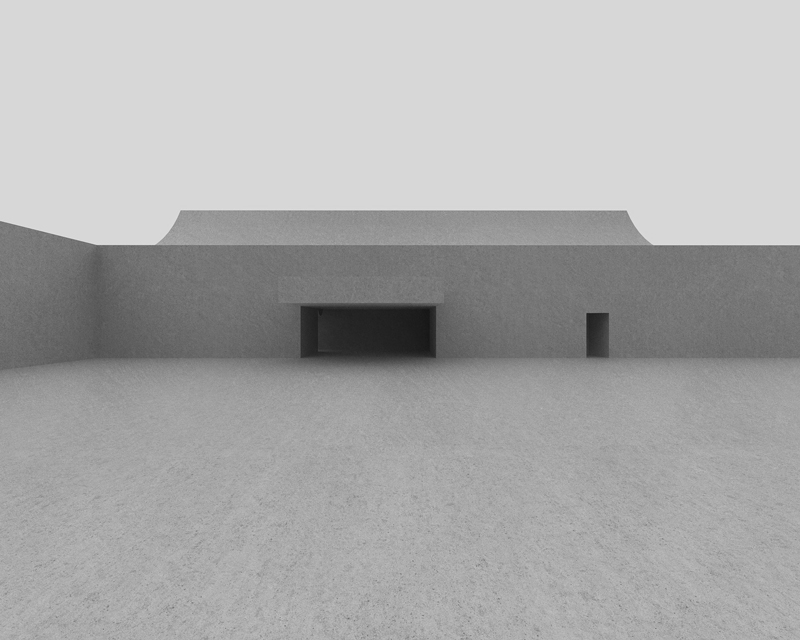

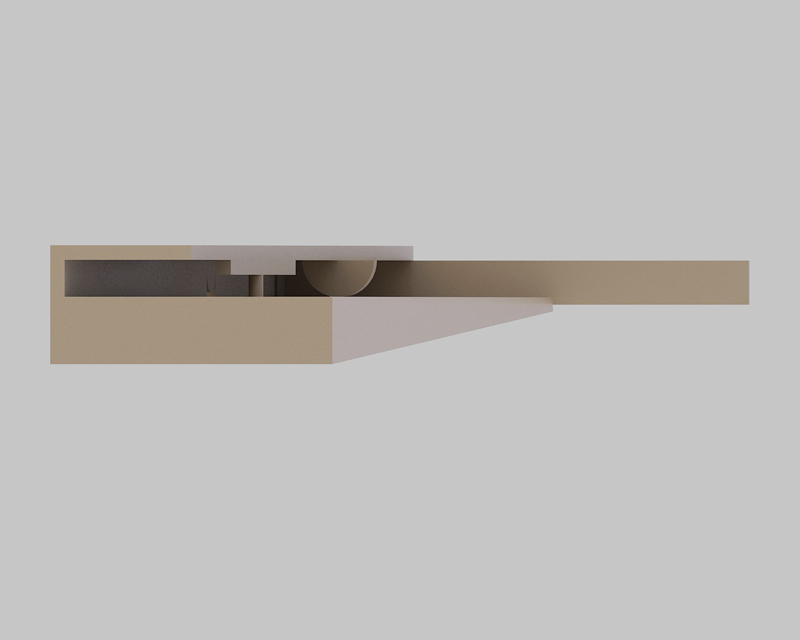

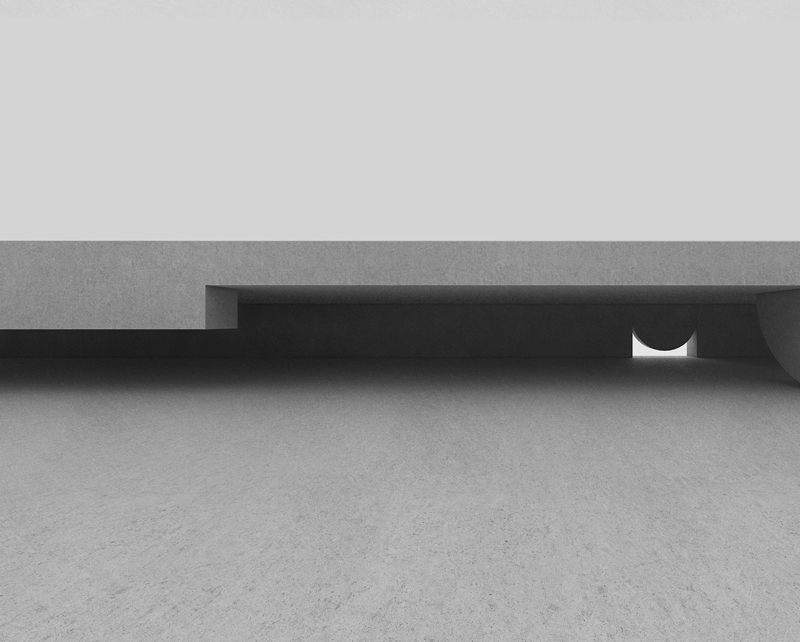

Labics, Model of Rome

Labics, Model of Rome

[1] The idea of Borderline Metropolis began in 2008 when we were invited to participate in the Venice Biennale, in the exhibition Uneternal City. Urbanism Beyond Rome, Section of the 11th International Architecture Exhibition, directed by Aaron Betsky, 14-33;

[2] We are especially referring to the cinema, with artist like Federico Fellini, Pierpaolo Pasolini, and photography; for an interesting overview on the contemporary photography on Rome: Marco Delogu, Chiara Capodici, “Rome: the travelling gaze”, in Uneternal City. Urbanism Beyond Rome, Section of the 11th International Architecture Exhibition, Marsilio, 2008;

[3] In the scientific literature on complex organisms the concept of instability is fundamental, because it permits the dynamic of self-organization and changes of state. Klaus Mainzer, “Strategies for shaping complexity in nature, society and architecture” in Complexity. Design Strategy and World View, ed. Andrea Gleininger and George Vrachliotis, Basel: Birkhauser, 2008

[4] As Cassirer reminds us, the truly ideal method, for Goethe, “consists in discovering the durable in the transient, the permanent in the changeable.” For Goethe, even in the most irregular phenomena it is necessary to manage to glimpse a rule that remains “fixed and inviolable.” Ernst Cassirer, Structuralism in Modern Linguistics, 1945; http://www.scribd.com/doc/95926777/Cassirer-Ernst-Structuralism-in-Modern-Linguistics-Word-No-1-August-1945-p-97

[5] Sanford Kwinter, “Who’s afraid of formalism?,” Any Magazine 7/8 (1994);

[6] Of this territory, 48% is agricultural; 15% is for green areas; 37%, equal to 47,730 hectares, hosts construction.

[7] This term substantially coined in the 1970s has recently come back into vogue as a possible solution to the mega-dimension of contemporary cities; the advantages of the “archipelago model” are, in fact, undoubtedly discontinuity, variation of scale and the possible construction of multiple identities; the risks are mainly the organization of the city into independent, separate enclaves, deprived of social and functional connections; the disappearing city is the scenario of the project of Oswald Mathias Ungers for Berlin, certainly the most important and significant model of an Archipelago City: The City in the City. Berlin: A Green Archipelago, ed. Florian Hertweck and Sébastien Marot, Zurich: Lars Muller, 2013 (Critical Edition, Original 1977);

[8] Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter, Collage City (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1983) 106-107;

[9] Pier Vittorio Aureli, “Instauratio Urbis. Piranesi’s Campo Marzio versus Nolli’s Nuova Pianta di Roma” in Pier Vittorio Aureli, The possibility of an absolute architecture. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2011, 85-140;

[10] During the course of the work, instability has been analyzed through four parameters:

Connectivity: which expresses and measures the capacity of a city portion to connect with adjacent areas and with the system in general

Density: which expresses and measures the concentration and compactness of a city portion

Functionality: which expresses and measures the level of functioning of a city portion, where functioning is defined as the capacity to satisfy the different needs of the inhabitants

Visual quality: which expresses and measures the capacity of a city portion to possess a physical and visual identity

[11] “If there is to be a ‘new urbanism’ (…) it will no longer be concerned with the arrangement of more or less permanent objects but with the irrigation of territories with potential; it will no longer be obsessed with the city but with the manipulation of infrastructure for endless intensification and diversification”: Rem Koolhaas, “What ever happened to Urbanism?” in S,M,L,XL, ed. Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, New York: Moncelli Press, 1995.

Bibliography

– Piero Sartogo et al, Roma Interrotta. Roma: officina edizioni, 1979.

– Italo Insolera, Roma, Roma-Bari: Editori Laterza, 1980.

– Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter, Collage City. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1983.

– Sanford Kwinter, “Who’s afraid of formalism?,” Any Magazine 7/8 (1994).

– Andrea Carandini, La nascita di Roma. Dèi, Lari, eroi e uomini all’alba di una civiltà. Torino: Giulio Einaudi, 1997.

– Ernst Cassirer, Lo strutturalismo nella linguistica moderna, Napoli: Guida Editore, 2004.

– Visionary Power, edited by Christine de Baan, Joachim Declerck, Véronique Patteeuw, Rotterdam: Nai Publisher, 2007.

– Uneternal City. Urbanism Beyond Rome, Section of the 11th International Architecture Exhibition, Venezia: Marsilio, 2008.

– Complexity. Design Strategy and World View, edited by Andrea Gleininger and George Vrachliotis, Basel: Birkhauser, 2008.

– Sanford Kwinter, Requiem: For the City at the End of the Millennium. Barcelona: Actar, 2010.

– Pier Vittorio Aureli, The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2011.

– The City in the City. Berlin: A Green Archipelago, ed. Florian Hertweck and Sébastien Marot, Zurich: Lars Muller, 2013 (Critical Edition, Original 1977).

Labics is an architectural and urban planning practice led by Maria Claudia Clemente and Francesco Isidori. The name of the practice expresses the concept of a laboratory, a testing ground for advanced ideas. Theoretical research and its practical applications form an integral and important part of the practice’s work. The research at Labics is geared towards an open, relational and structured architecture, capable of guiding the transformation of a context and of a territory defining new social and urban geographies. Public space, intended as a place of construction and representation of an open and democratic society, always holds a central role in Labics’ research, from the more theoretical projects like Borderline Metropolis to urban master plans such as La Città del Sole or the Torrespaccata masterplan in Rome, but also in architectural scale projects, like MAST Bologna, Piazza Fontana in Rozzano (MI) and the Italpromo & Libardi Associates headquarters in Rome. In the past few years the office gained several awards, among which the Iconic Award, the Chicago Athenaeum, Inarch-Ance and Dedalo Minosse. In 2015 MAST has been shorlisted for the Mies van der Rohe Award. Labics has been invited to participate to several exhibitions, among which the 11°, 12° and 14° Venice Architectural Biennale and the recent monographic exhibition “La Città Aperta” during the Berlin architectural festival “Make City” (2015).

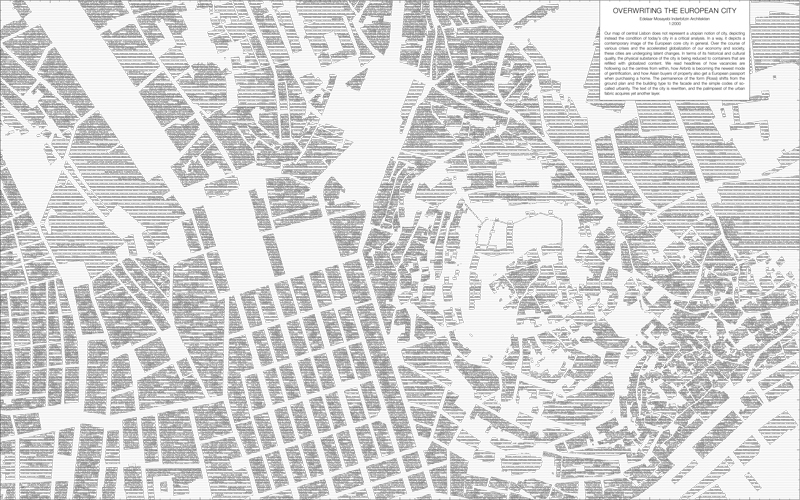

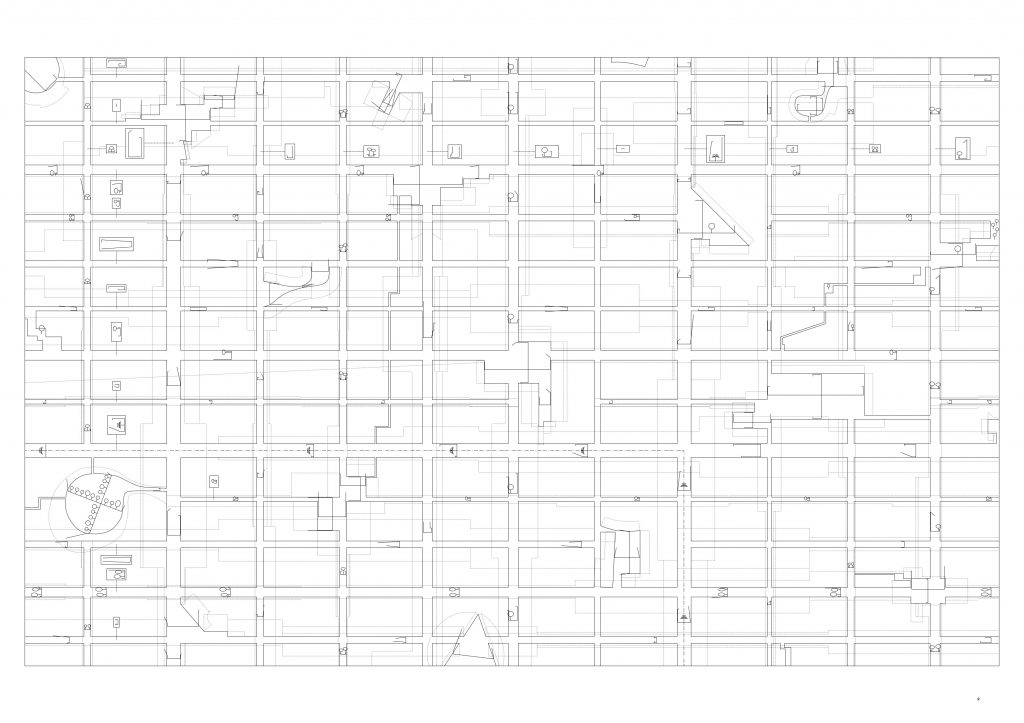

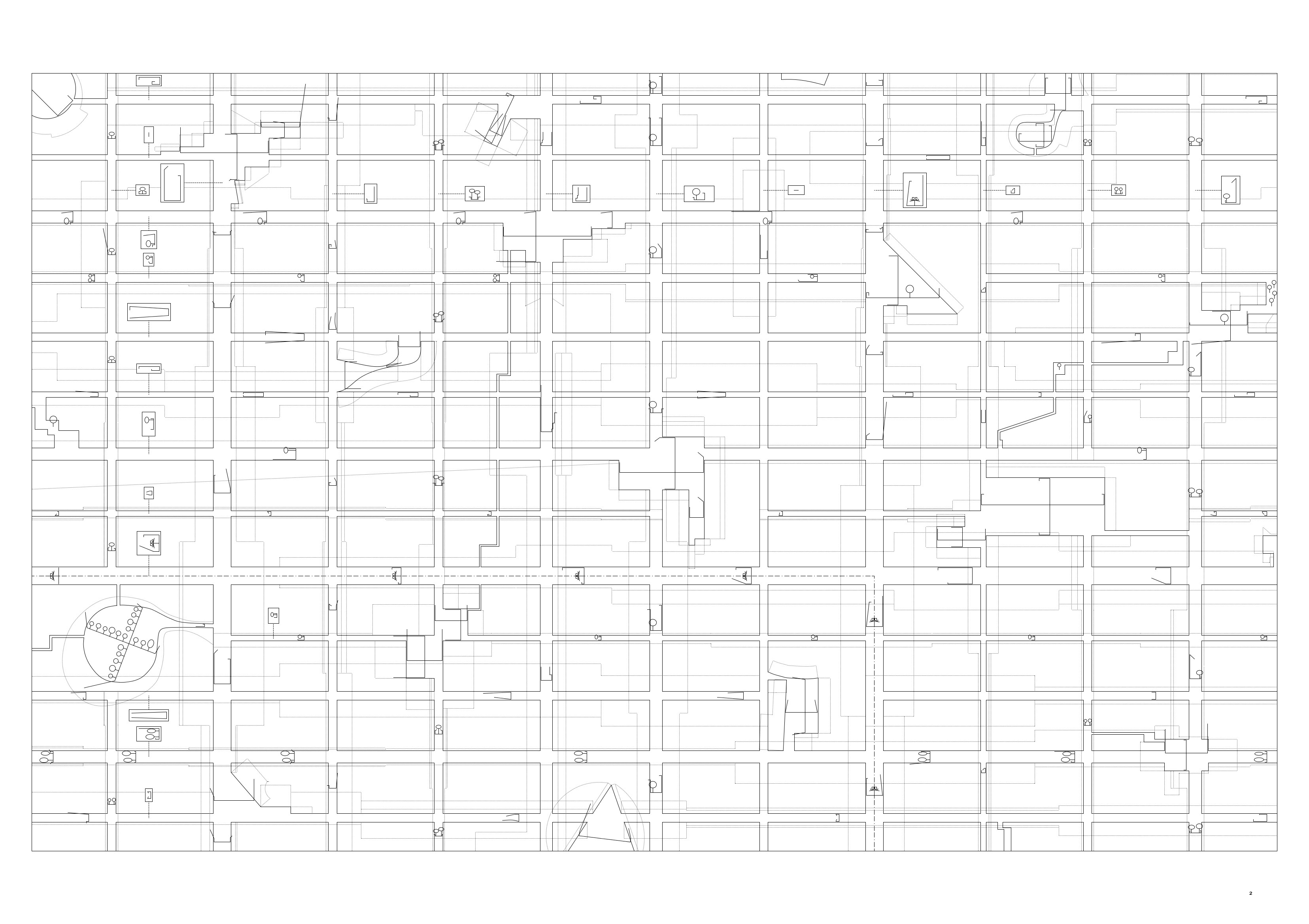

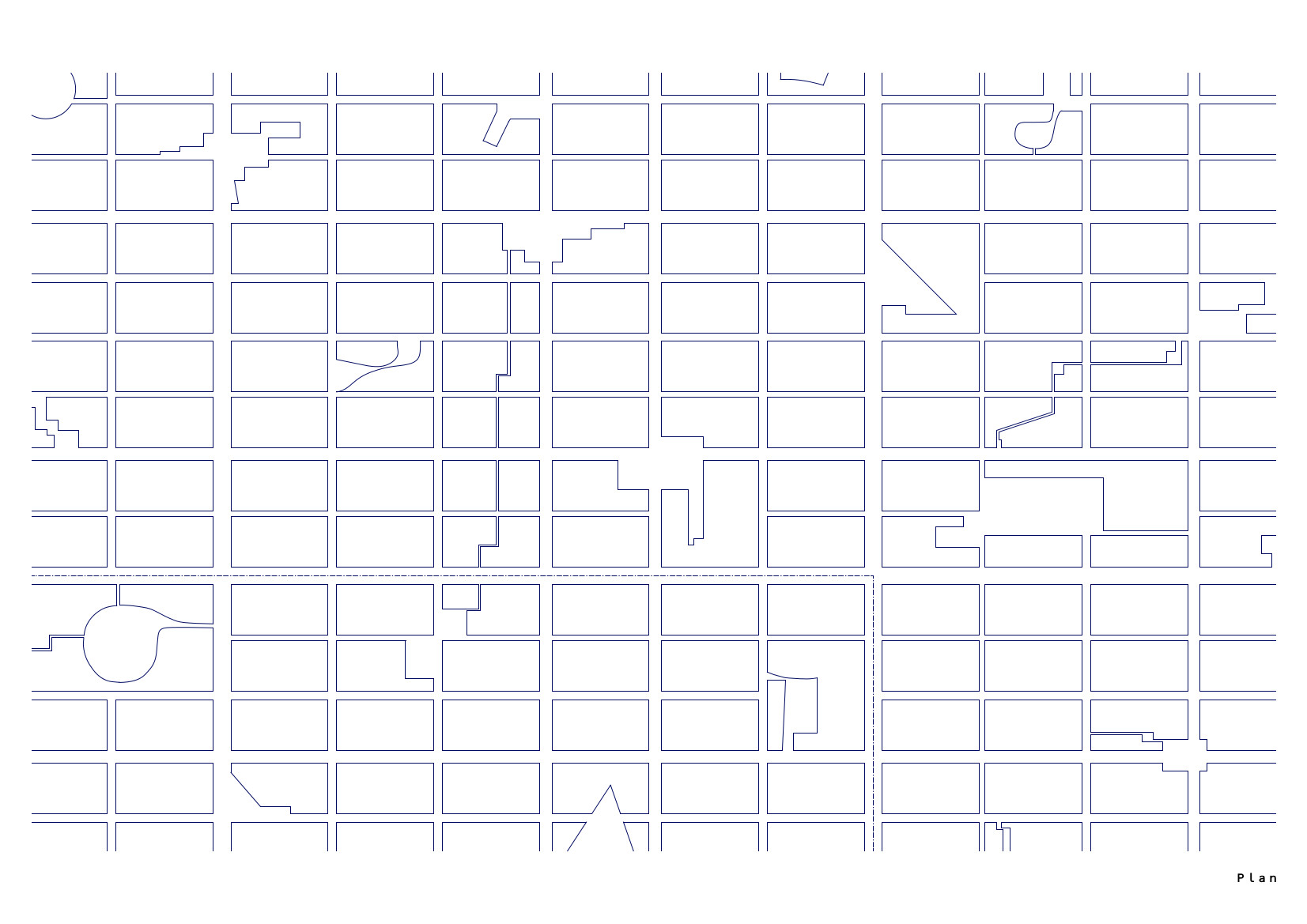

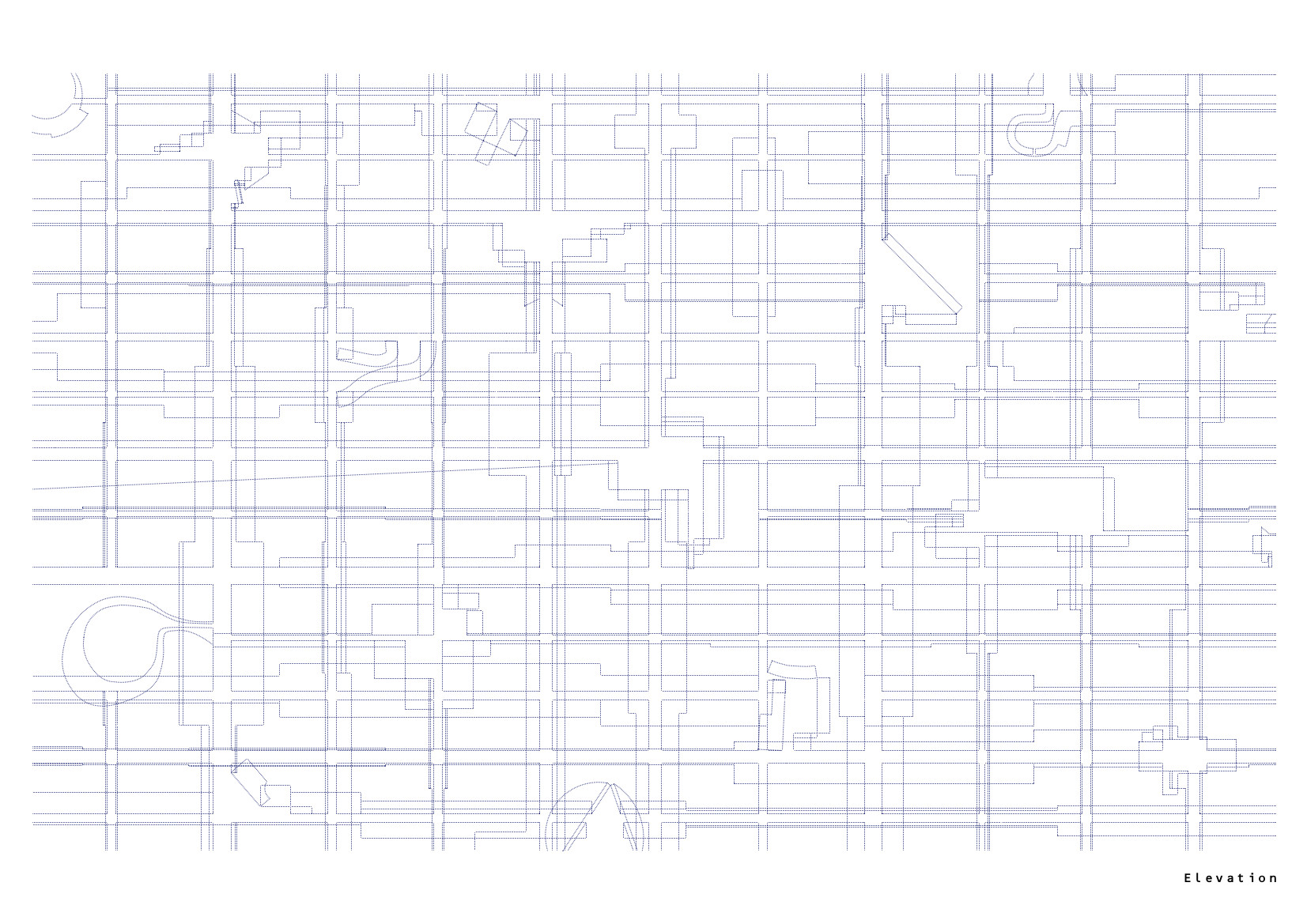

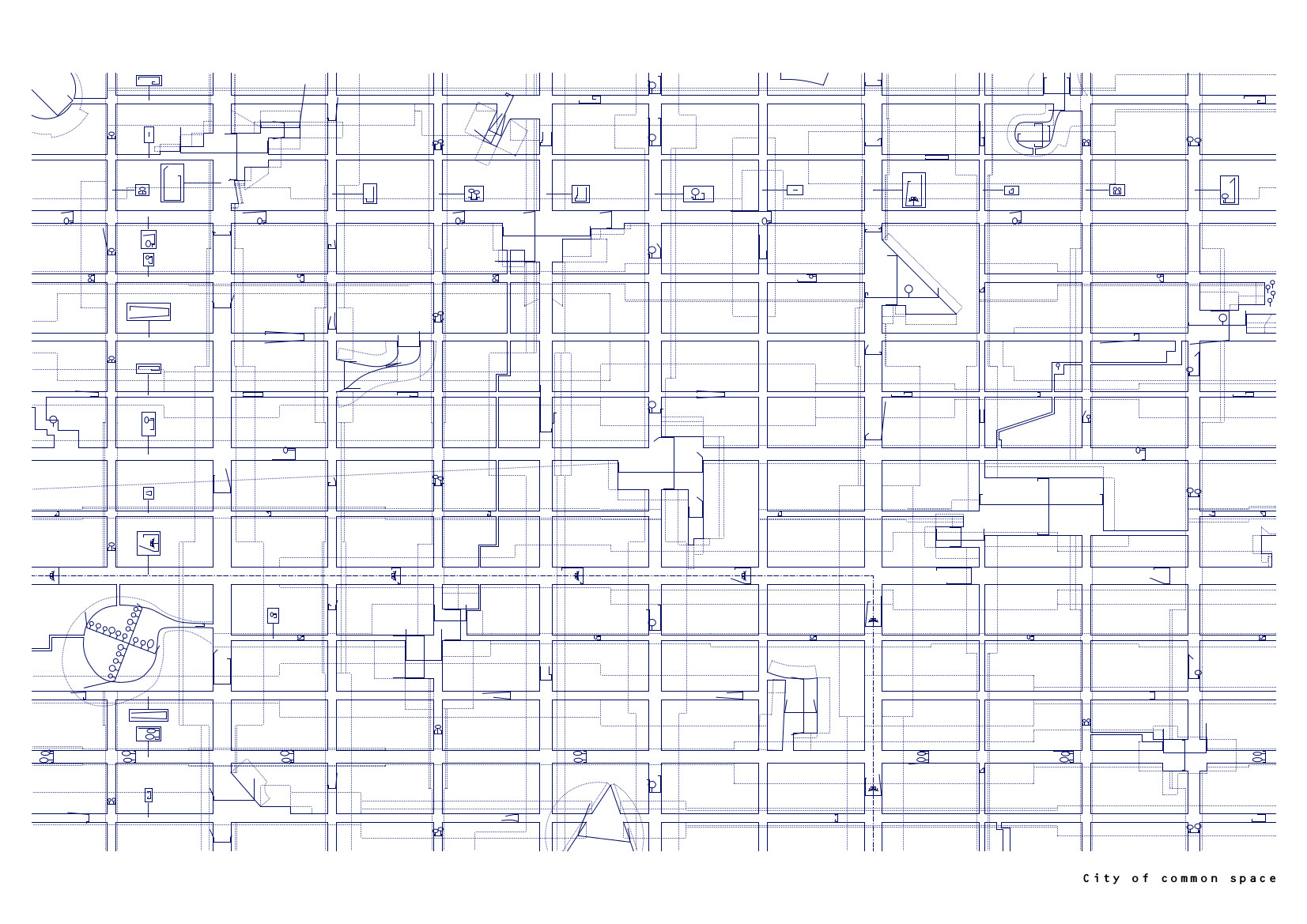

Like most cities, it began with a Grid, which made sense when we had to navigate, remember, negotiate, and find our own way. Its single-mindedness physically structured all parts into a whole, providing orientation, location, address, memory, and identity. It made things much more manageable and rational. We had a sense of where things stood in relation to each other.

Like most cities, it began with a Grid, which made sense when we had to navigate, remember, negotiate, and find our own way. Its single-mindedness physically structured all parts into a whole, providing orientation, location, address, memory, and identity. It made things much more manageable and rational. We had a sense of where things stood in relation to each other.

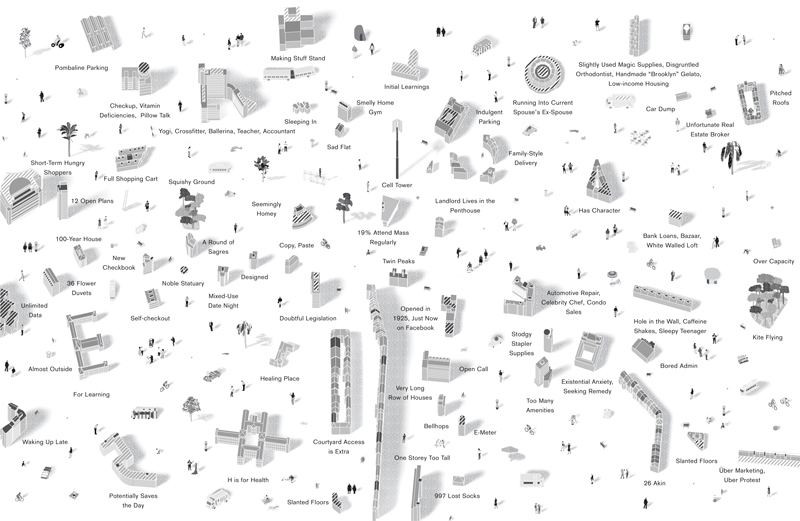

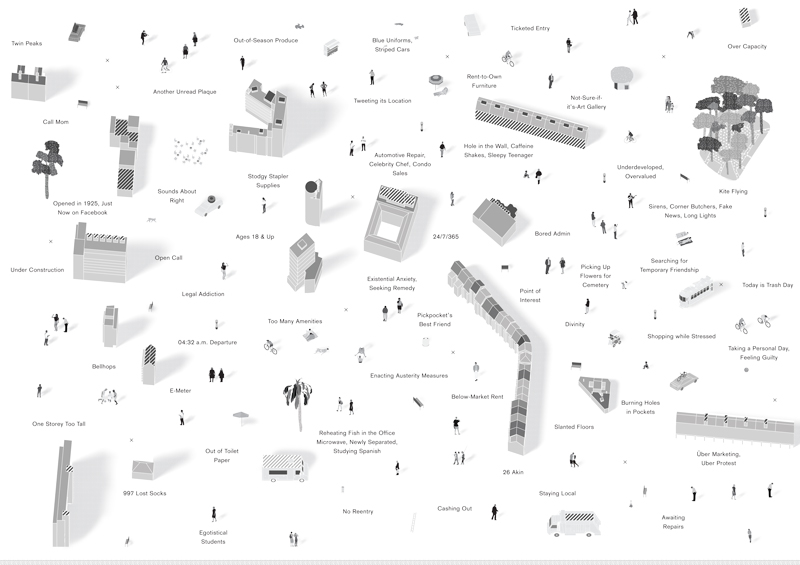

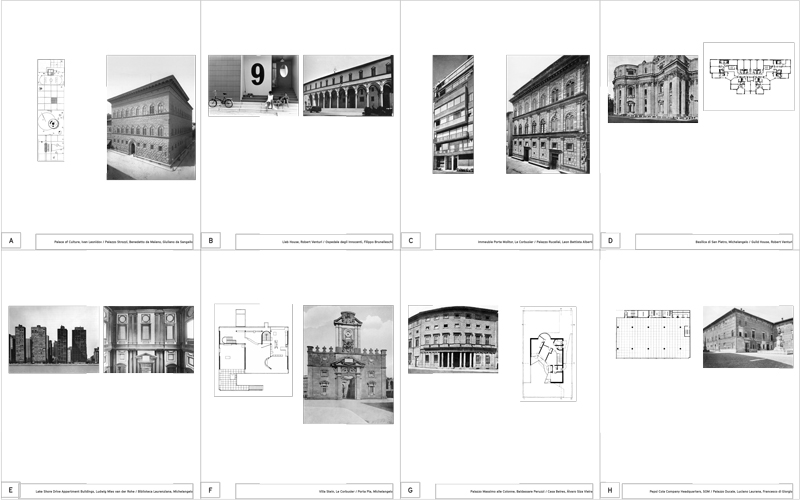

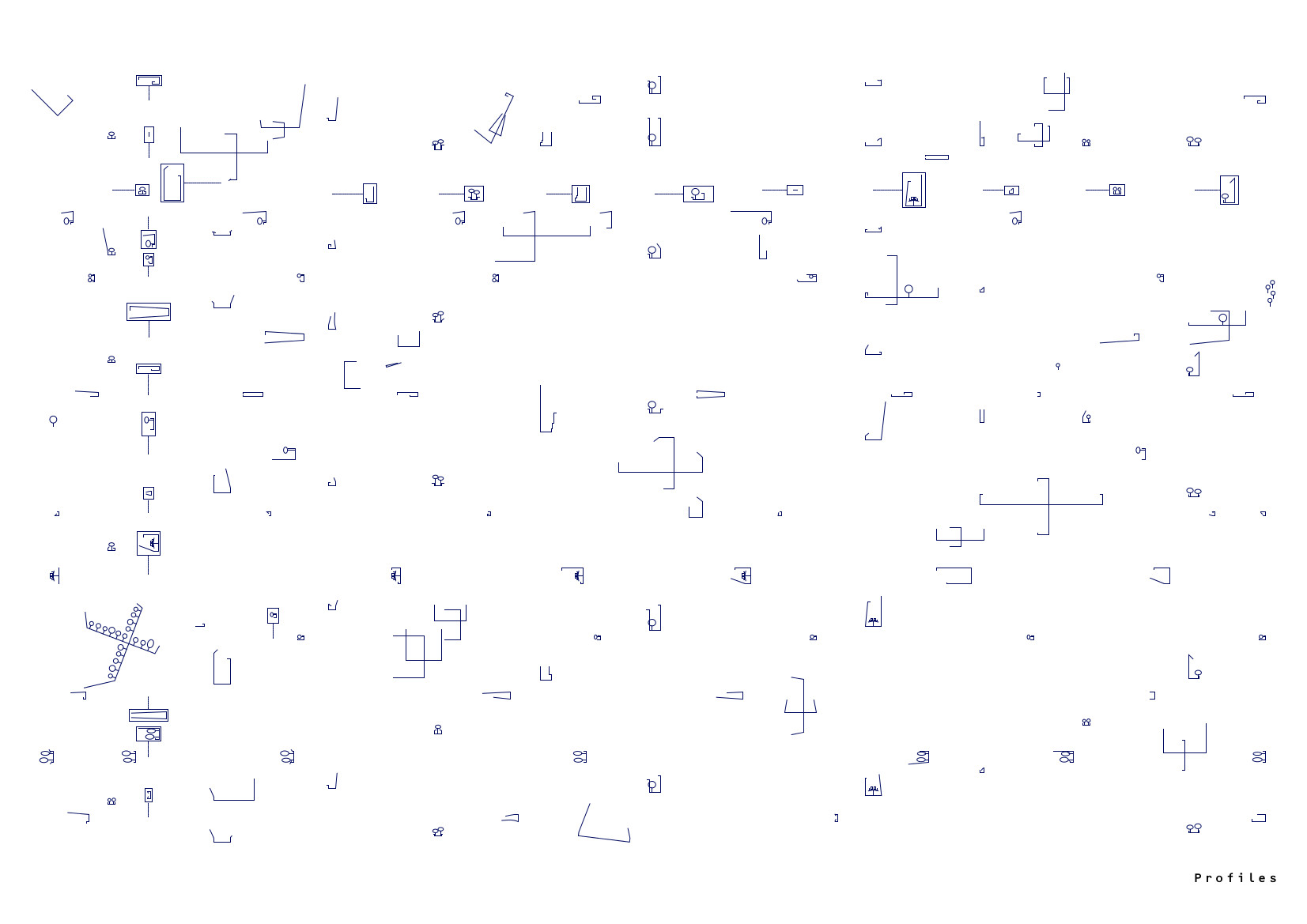

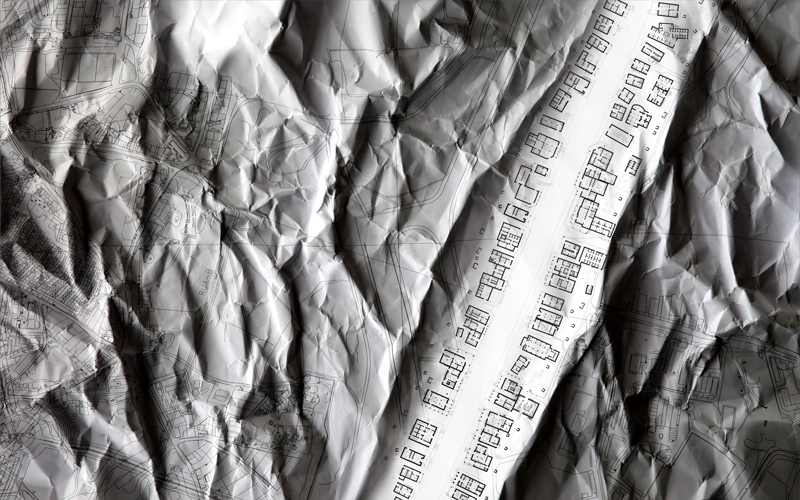

In our work we operate in an imagined architectural universe, a kind of ahistorical deep space in which works from all epochs meet on the same plain. Here, unexpected friendships are forged, coupling into surprising partnerships.

In our work we operate in an imagined architectural universe, a kind of ahistorical deep space in which works from all epochs meet on the same plain. Here, unexpected friendships are forged, coupling into surprising partnerships.

Outer Kinds of Structures

Outer Kinds of Structures