There’s something about Clients

Enrique Peláez

Being a client in its broad sense “the inception” Saenz de Oiza, a famous iconoclastic Spanish architect, whose work became prominent in the 1950s and 1960s, used to say that projects are as good as a client can be. Nowadays, when delivering architectural projects it is hard to define what a client is, and more […]

Being a client in its broad sense “the inception”

Saenz de Oiza, a famous iconoclastic Spanish architect, whose work became prominent in the 1950s and 1960s, used to say that projects are as good as a client can be. Nowadays, when delivering architectural projects it is hard to define what a client is, and more importantly identifying it in complex project structures where a client can have multiple heads. Is the client the one who pays the fee? who will enjoy the project once accomplished? Whether a client has some commercial connotation or not, a client is the point of departure of a project, where all begins, the source of a need that looks forward to turning out into something that has not ever done before.

Its expectations in the construction industry

The uniqueness of the construction industry, as opposed to the manufacturing industry whose aim is to provide goods in a serial manner and with controlled risks, is rarely appreciated by clients who seek only for profit, and see architects as adding excessive costs and unnecessary to projects. Nevertheless there are some other clients who invest time in explaining its needs in order to be translated into a vision that facilitates the discussions that will derive into a rich dialog that all architects would look for when doing their work. Both types, despite not the only ones, are valid and legitimate options as long as the expectations are set from the very beginning.

Client types, complex structures

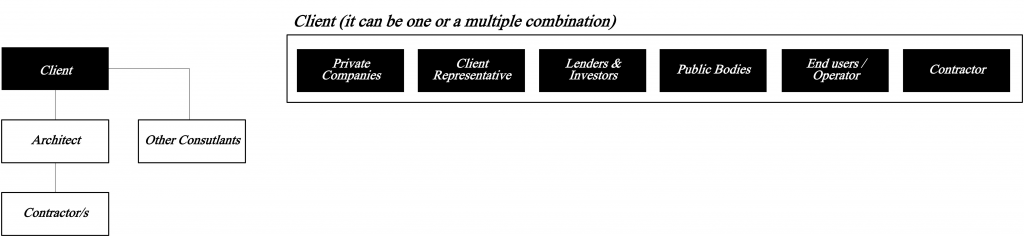

There is a range of client types which may be categorised by key characteristics. Some of the categories of client that are likely to be encountered in practice include: public bodies, including local authorities, who are experienced and have a large and wide portfolio; large commercial developers; and large and small companies who build to improve and extend their business and are thus owner occupiers. These different client types will have different needs that must be explored in order to build up a fruitful relationship from which the project can benefit. Although each client is different, very often clients are increasingly adopting a project culture in all aspects of their business, which added to the usual stakeholders surrounding a project, are resulting in high demands and constraints when appointing an architect. This is something that should not be necessarily badly received since working with limits is a challenge rather than a threat in a design process; however, these complex client structures most likely end up in a misalignment of the project goals and a lack of decision making.

During the project life, and within the spectrum mentioned above, clients are mostly linked to stakeholders. These stakeholders range from operators/end users who can actively participate expressing its needs for using the project, to Contractors: who could even become a client in design&build contracts, to Lenders & investors: who expects to obtain a return on the project investment and to Public bodies, whose interest is to bring somewhat value for the community/society. Additionally, it exists the role of client representative. As the name implies, a client representative represents the interests of a client, this set-up is frequently used by those clients who do not have the in-house knowledge to cope with the project, instead they prefer to delegate the management of the project to another professional entity. There are multiple combinations on which these different roles can be played so as to be a client or a stakeholder but irrespective of the term used in a specific project they all fall under the client’s umbrella.

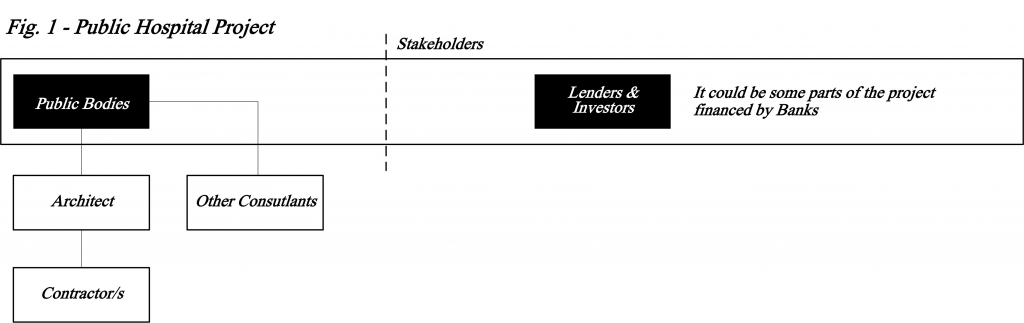

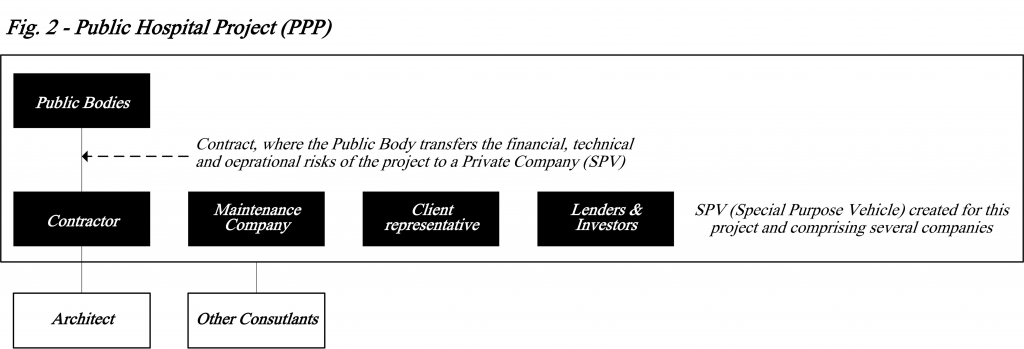

An example would be a Hospital project. In a full public hospital (fig. 1), whose capital expenditure is funded by the public administration, the client is concentrated into one or perhaps 2 entities, whereas a public hospital developed in a PPP (Public Private Partnership) mode (fig. 2), an specific entity called SPV (Special Purpose Vehicle) acquires the financial, technical and operational risks of the Project, and the client embraces several parties.

How to maximise the architect relationship with a client, “bridging the gap”?

With this in mind, it is inevitable that architectural practices are continuously empathising with clients, as opposed to the times when Saenz de Oiza realised his work, and are consequently becoming machineries that react and respond to these needs. To do so, they have to be equipped with multidisciplinary teams with a great variety of skills and backgrounds not only to provide enough confident to clients but also to manage the expectations of both, client and architect, and understand scope in that sea of interests that can frequently be found in a project. In the end a successful project can be seen as that which better captures the needs of your client, which regrettably might not be remarkable architecture.