Sharing without dialogue

Andrew Mackintosh

In Architecture we are in a position in which we can share our work and thoughts without the need for written or spoken word. Through drawingS we have the ability to communicate with one another on a common basis and exchange on an agreed method of representation. With plan, elevation and cross section, we share […]

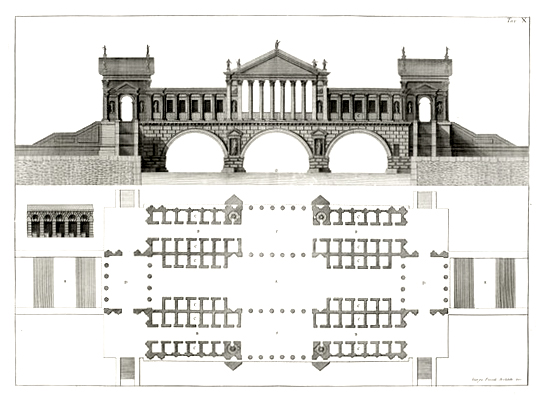

In Architecture we are in a position in which we can share our work and thoughts without the need for written or spoken word. Through drawingS we have the ability to communicate with one another on a common basis and exchange on an agreed method of representation. With plan, elevation and cross section, we share all the facts required to construct a building and explain its use. This is an extremely clear and concise method of sharing information, one could say it is similarly found in mathematics, through working almost exclusively with numbers and symbols, ideas are able to be exchanged and understood universally.

During this process of translating thoughts into an accessible format, we gain the skills necessary to later analyse them. It is fruitful that in the experience and knowledge we gain through producing drawings, we expand our own vocabulary in reading drawings.

Analysts learning by doing

Let’s take an escape stair as an example, this is an area usually completely reduced to its minimum legal and functional requirements and is one of the most easily identifiable objects in our catalogue. Once you have had to design and move around a fire stair in a couple of different projects, you begin to understand the requirements and rationale which lead to that element being placed in that exact position within a building. In this way we can think of them as a kind of pictogram, a symbol on a plan which you can almost immediately visualise and comprehend.

With more time we continue to consciously record our experiences and define categorisations for Architecture. You can’t put Architecture in boxes, but you can recognise through analysis that what you’re looking at is a hotel for example. Through our everyday working with the basic architectural elements such as door, window, stairs, we can not only directly get an idea of size, scale and proportion from a drawing but then formulate educated assumptions as to its function.

Fantasies in the undefined

Of course in this act of sharing through drawing, we lack key parts of an Architecture which we require to allow us build a real picture in our minds. In most cases materials are lost and the reader must begin to speculate on what sort of finish would be in this space, how would it be treated, what colour would it be? These are critical points in helping construct a complete understanding of what someone is trying to share. However, one can look at these lapses of information as an opportunity to romanticise about what we would like to envisage.

What one can conceive as a strong solid space of white concrete with a light green marble floor and dark oak doors, might in reality just be plasterboard walls with a carpet floor and plastic doors. This possibility to fantasise through the missing pieces creates an internal dialogue in which we begin to expand our own wishes and thoughts in the context of what somebody else is providing us.

Stranger than fiction

The way we can communicate with one another fictional architectural ideas without the need to produce a physical building is a very cathartic experience. From the freedom of the drawing board, one can propose and express the radical and take it no further than a pulse of expression with no commitments.

Nevertheless, we must then ask the question whether a drawing ever become a piece of Architecture if it does not go through the final obstacle of being built.

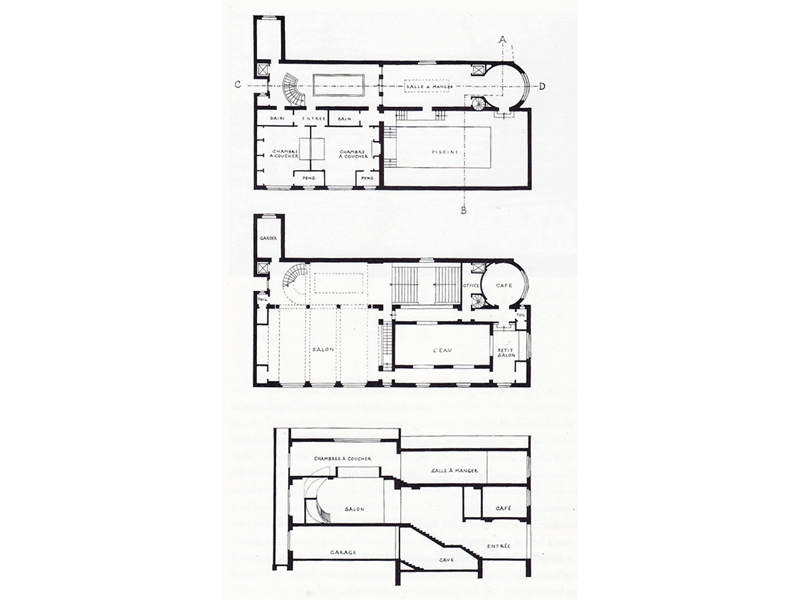

Think of the Baker house by Loos, in this unbuilt masterpiece, through its drawings alone, we are provided with all we require to distinguish it as piece of Architecture. We can picture what lifestyle would exist in this palace for the glitterati, the champagne fuelled parties of the voyeurs and how one would inhabit the spaces, walk around and swim in the pool. Similarly to Palladio’s design for a Rialto bridge in Venice which appeared in his 3rd book of architecture, the project was never realised but had been so widely published that it represents the Palladian Bridges as a building type.

The ability for a piece of work to continue even after physical destruction through the medium of drawing is reassuring for its capability to carry on a participation in Architecture.

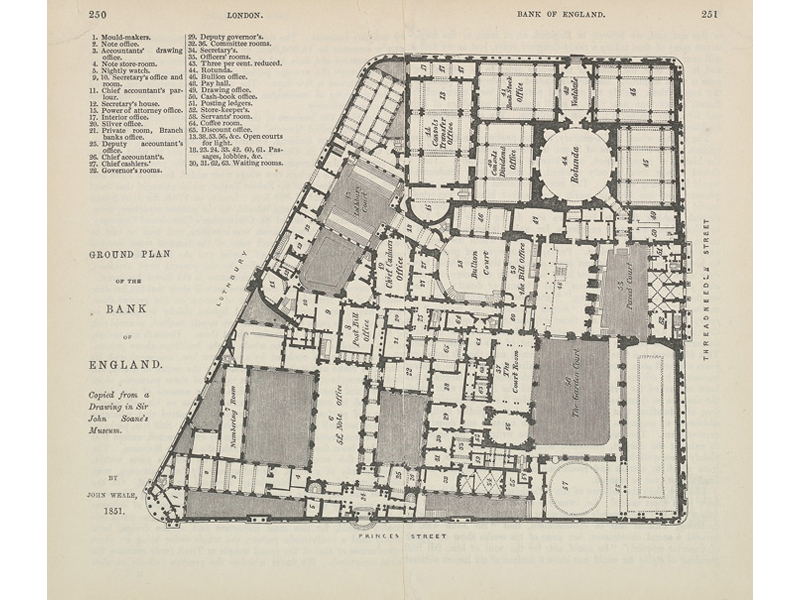

Perhaps one of the most recognisable and overused references for this, is the floor plan for the Bank of England by Soane. It is intriguing by its complex arrangements and legendary by its destruction. Nearly 100 years after its demolition, all what we are left with today is a mere outer wall and the drawings in which to analyse this Architecture which use to live.

Perhaps, however, this interest and trust only works for projects of a not so distant past, if we had no accurate record of the floor plan from Soane, would we still be so enticed by it? The lack of hard evidence could, in this case, destroy any truth we hold on such a project and reduce it to an indeterminable study and piece of mythology.

A Monochrome Manifesto

Through the accessibility of communicating by drawing, ideas are able to continuously resonate in our discourse of Architecture and enable borderless debates without the need to be physically present. While this is certainly in our consensual approach of sharing at the moment, drawing will always remain completely undemocratic.

In this way we have a particularly eccentric medium; we define enough of a common language by consensus to understand each other while allowing ourselves enough space to define our own attitude and position within the established frame. The “It’s not what you say that’s important; it’s how you say it” approach of representing one’s self. This inevitably produces mixed results, some in which representing is more important than content and vice versa.

By creating these wordless manifestos we put ourselves in the best position for being read in the future, we define everything and nothing, all at the same time. Without writing we give no solid explanation for our reasoning, no guidebook or precise statement to be attached to. Instead, we use a mixture of common values and individual attitudes to share our positions with one another.