This changes everything; Architecture of the Commons

Antoine Prokos

The narrative of architectural history is a powerful tool for theory, if not the authentic form of theory in our discipline. It is of course being continuously analysed and debated with a huge degree of complication. Nowadays, 40 years after the reformulation of the context of architectural history by Manfredo Tafuri and his gang, merely […]

The narrative of architectural history is a powerful tool for theory, if not the authentic form of theory in our discipline. It is of course being continuously analysed and debated with a huge degree of complication. Nowadays, 40 years after the reformulation of the context of architectural history by Manfredo Tafuri and his gang, merely going into the matter demands an immense amount of theoretical precision, in order to avoid repeating common knowledge or, worse, contributing to the pile of meaningless pseudo-theoretical alchemy. Nevertheless the debate is far from closed, especially if we consider new urgencies and new concerns, more real than ever. The agenda of a hundred, fifty or even ten years ago cannot be taken into account in the same way as before. We need to fish for new meaning, for new stories, so here are some thoughts about a possible one.

While the now orthodox debate on operative criticism was still radical and revolutionary, one of the founding principles of architecture as we know it was silently getting scrutiny under an angle of huge pertinence. The Doric temple, the „starting point for European architecture’’1 might have been born through a process much less self-referential than we thought until now. In 1990, Goerd Peschken, German archeologist and architectural historian published a text called „Demokratie und Tempel“2, temple and democracy. Based on the abundant visual material published by Rudofsky (3) and an earlier study by another historian, Hans Soeder (4), he attempts to explain the ancestry of the Doric order within the functional vernacular of granaries. Peschken, following Soeder’s trace, observed the similarities between the triglyph-metope sequence and the lateral walls of various types of vernacular granaries, ventilated with thin vertical openings in a rhythm of plain parts and regrouped slits. In addition, a picture of such a barn is a pretty self-explanatory statement on the columns and the capital. To protect the grain from rodents, the construction is placed on top of columns themselves finished with a horizontal plate. According to Peschken, often added to this capital were pieces of cloth drenched in repellent (Ionic order) or acanthus leaves (Corinthian order) that are naturally unpleasant to vermin.

Peschken’s work has come back to light with the third issue of the French architectural journal „Marnes’’, which brought along an initial debate on the implications of the matter. Most notably, in an article published in the same issue, Philippe Villien proposed to look at Peschken’s interpretation of the Doric order in line with Banham’s pledge for the well-tempered environment (5). The thick roof and the triglyph as ventilation apparatus support such an idea, but can we run away with reiterating a well-known and decently understood point where there is room for so much more? Where Villien sees an argument about climate in architecture, there is probably the missed opportunity for symbolism that goes much further than the hierarchy between structure and tubing.

Despite this argument that is no worthy counterpart to the opportunity at hand, the French architect grasps the most important point that we all need to acknowledge; „Demokratie und Tempel’’ is an excellent starting point for a very important evolutionary step in the current status quo of architectural theory. If not a call for the complete reversal of our knowledge, these observations offer a new, stimulating possibility for the whole moral genealogy behind architectural thought. Until now we thought that a given structure, the temple, invited reflection through its special character on the perfect construction and led to the sublimation of previous construction. Peschken’s and Soeder’s assumptions link this open question of the language of architecture with the most pure form of collective meaning: the agricultural and territorial organization that is the one and only origin, the unique true subject of common existence as we know it.

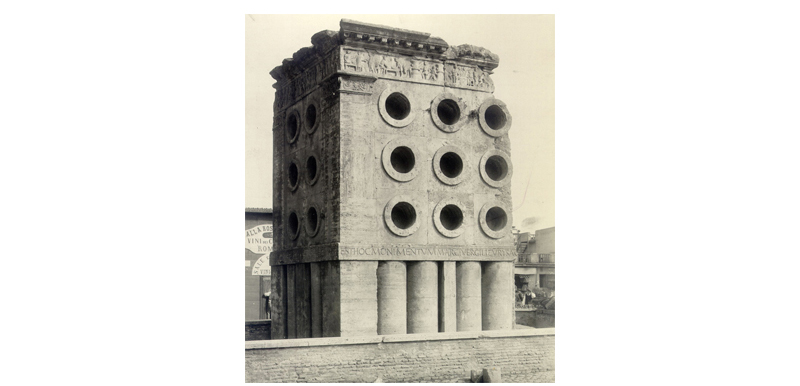

It goes without saying that the topic of the commons has always been current. While ancient Greece coped rather simply with the issue, maybe in part thanks to the symbolic power of the temple, the Roman Empire had a pronounced dependency to a much more complex scheme. With its accomplished territorial management and the powerful soldier-slave feed- back loop, it achieved a very high level of sophistication in the distribution and transformation of common goods (6). Although the Doric order had been almost forgotten by the time Rome started its expansion (7), there is evidence for civic architecture with explicit symbolism related to the commons within the intriguing artefacts that the empire left behind. Not least so would be the tomb of Eurysaces, the freedman baker.

The symbol retained for this tomb is mostly that of the freedman. (8) Its’ outmost significance is understood inclusively within social status, underlining the importance of family line within the roman empire and the struggle of the former slaves, the bourgeois of their age, to elevate themselves and their families into some form of posterity. But the most important symbol might be the other one, that of the baker. The ornament of the tomb stems in fact from Eurysace’s occupation. The round motives on the façade are alleged to correspond to the measuring units of grain (9), thereby making a posterity for those, if not for Eurysace’s family. The passage from the form of the granary to the rules of bakery is very well suiting to schematise the different hierarchies in the handling of resources between the Greek and Roman periods. The question is no longer about the collective capacity to provide society with grain, as that is taken for granted, but much more about individual capacity to succeed through transformation of a resource that is given. This dislocation in a vast scale is the same one operated since a couple of centuries. It is at the very center of our own predicament.

There is an opening here to move towards the crisis of the present, the environmental crisis, while refraining of course from theorising any form of sustainable development. This term in itself has become a label for an anti-theoretical phantasy, a form of wishful thinking already lurking within Banham’s technological dream. It isn’t a secret to anyone that the modes of common existence, embodied in their initial purity by the temple, need profound questioning in their current form, 2500 years later. This interpretation is getting more current every day, with the problem of the 21st century rapidly emerging not as a mere problem of technology but as an inclusive ethical problem, a problem of capacity, of resources and of mere honesty and morality towards the commons. This naïve speculation on language doesn’t offer any solution to the current set of problems, but I hope is a clear introduction to something worth sharing.