Grafton Architects

Matilde Girão

Living in a network culture, where communication travels at a speed of a link, we position ourselves to stay one station away from a destination. Plugging in/out; switching on/off; signing in/out is our response to a working agenda. There is no address to where the interview took place. There is a common virtual space of […]

Living in a network culture, where communication travels at a speed of a link, we position ourselves to stay one station away from a destination. Plugging in/out; switching on/off; signing in/out is our response to a working agenda. There is no address to where the interview took place. There is a common virtual space of communication.

„(…) supermodernity produces non-places, meaning spaces which are not themselves anthropological places and which, unlike Baudelairean modernity, do not integrate the ear- lier places: instead these are listed, classified, promoted to the status of “places of memory”, and assigned to a circumscribed and specific position” (Marc Augé, Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, 1995, p. 77-78)

It was both 4pm local time, in Dublin and in Lisbon. Our distance was as far as logging in; entering our username and accepting the invitation to establish a virtual connection space via Skype – a telecommunication video chat. And that’s that. Proving right our condition in today’s society, from that moment on, we were both conditionally framed in each other’s screen. There was no place of reference, but an ephemeral transitional entity.

Sharing common grounds since 1970, Shelley Mc Namara and Yvonne Farrell, both graduates of UCD – University College Dublin – established Grafton Architects in 1978. They are Fellows of the RIAI (Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland); International Honorary Fellows of the RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) and are elected members of Aosdána, the eminent Irish Art organization. They have recently won the fourth annual Jane Drew Prize.

What is the meaning of confrère to you?

By confrère you mean collaboration?

Exactly. As a form of engagement between architects.

Right. I think Architecture is a collaborative endeavor. Whether it’s within the studio or beyond the studio. In one of your questions, from the review you sent previously, you ask about Group 91 and how the collaboration worked. Maybe I’ll speak about that first and then come back to the meaning of the word. Why and how did people alert you?

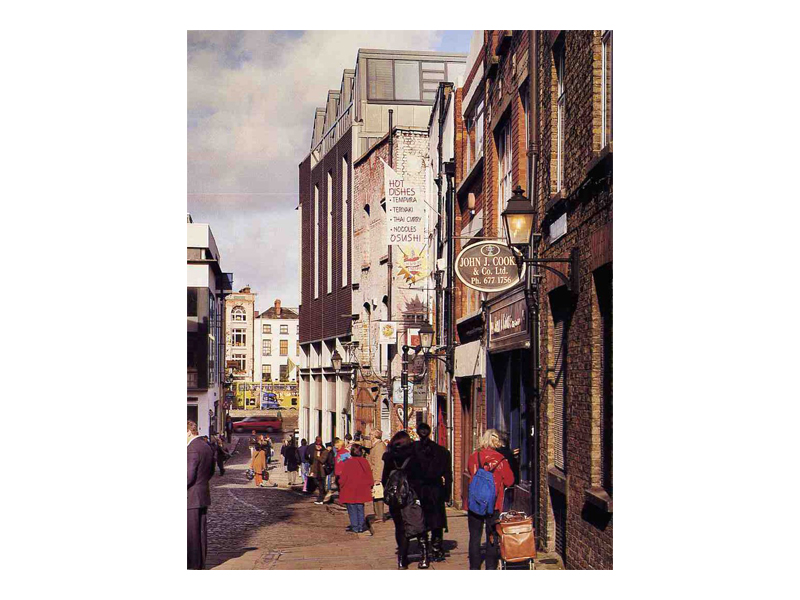

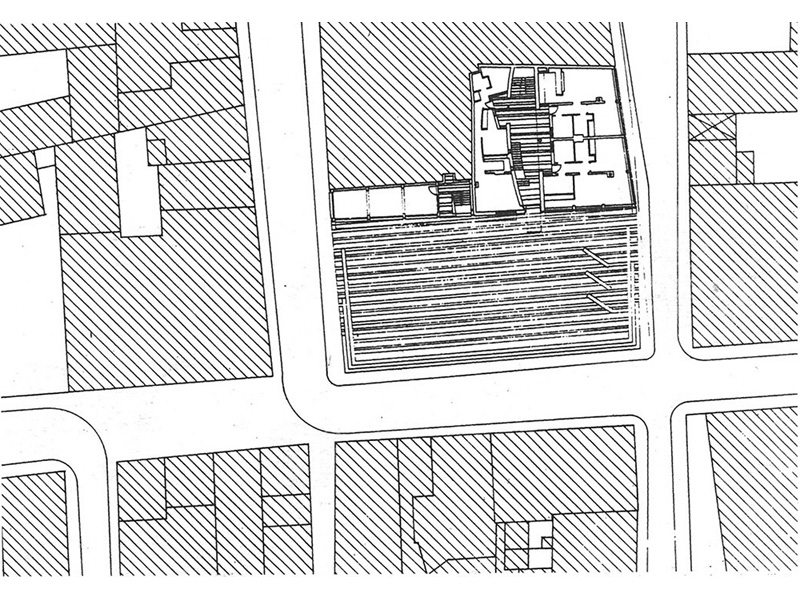

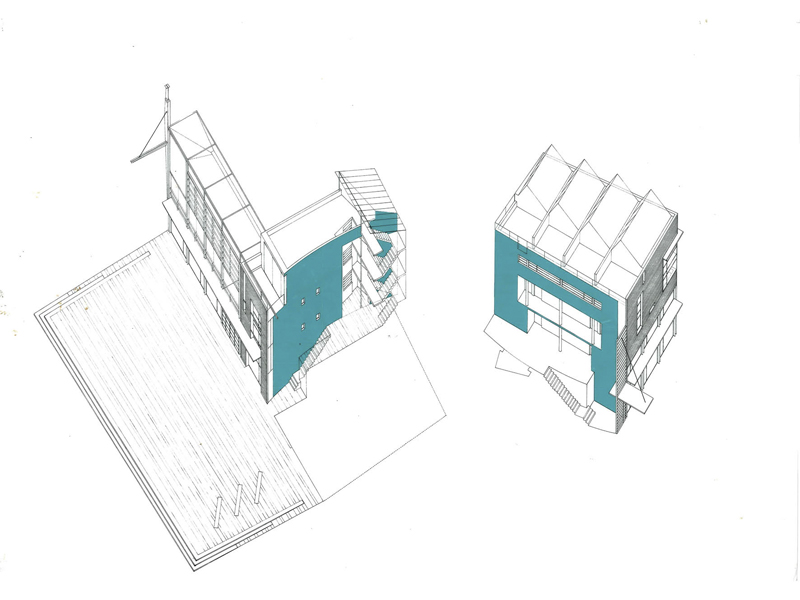

So, in Ireland, I think without us realizing, three generation of architects were teaching together ever since being students together. And, what happens when you are teaching together is that you develop very long conversations and, again, maybe without us realizing, we were developing a common ground. Our common ground for Group 91. We felt, especially in Ire- land, that there was an architectural culture to be built. We were conscious that in other countries there was a much stronger culture of contemporary 20th-century architecture and this is to do with the fact that we were a young country in terms of our independence. And there were a lot of issues, I suppose, of identity and many of these things. So, Group 91 happened because this was in the air. And when in 1991 Dublin was City of Culture, we knew it was time to react and do something. We came together to make a project, which was about developing new typologies based on the eighteenth-century houses in Dublin – eighteenth-century Dublin is a city of houses – and because at that time it was quite derelict in the city center, we felt that it needed its streets rebuilt with new house types. So that was our first reason for setting up Group 91, to make this exhibition. Then because this group was already formed, when a competition was announced for the regeneration of a very large quarter in Dublin, called The Temple Bar, we were shortlisted to be one of the practices to enter this competition. We were against all the big commercial offices including some international commercial offices – SOM. So a group of seven small practices came together to make this competition and we won.

And did you have a sort of group manifesto?

We had an unspoken manifesto that we had developed over time. We believed in the repair of the city. We believed in the idea of city as a series of layers not needing the tabula rasa approach and so we took, not knowing the word at the time – which Manuel de Sola Morales coined – which is the Urban acupuncture philosophy. That was what we were doing – repairing and stitching back this piece of city together. So it was a very exciting and important time for us. For seven offices to come together was not an easy task and what was good was that each practice came to make one project.

Ok, so this was the starting point?

Yes, this was the starting point. And going back to your question about confrères, in general, I think there is a strong connection between teaching and practice in architecture. We find this a very fruitful relationship. We try to make our office1 feel like a studio. We absolutely believe in collaboration as the very core and basic idea in the practice of architecture.

I imagine this also links to the number of collaborators you have in your studio.

Yes, we keep our studio quite small. The largest we have ever been is 21, maybe 22. This is probably, at the limit of being able to have a very direct and personal relationship with each project and with each group, allowing to cross-fertilize between groups, so that sometimes a group of people working on one project jump to reinforce another, which we believe to be one of the most important resources as a practice. For instance, recently we are doing two competitions and, the instinct is to break down the practice into two teams but we decided not to do that. Instead, we decided to group ourselves together in a melting pot, so to speak, for a short stage and only divide for the final production. We believe in the chemistry and the accident that happens when you ask a diverse group, with diverse talents, to think about one thing. And sometimes it’s the outsider that makes a comment or a proposal that acts as the catalyst.

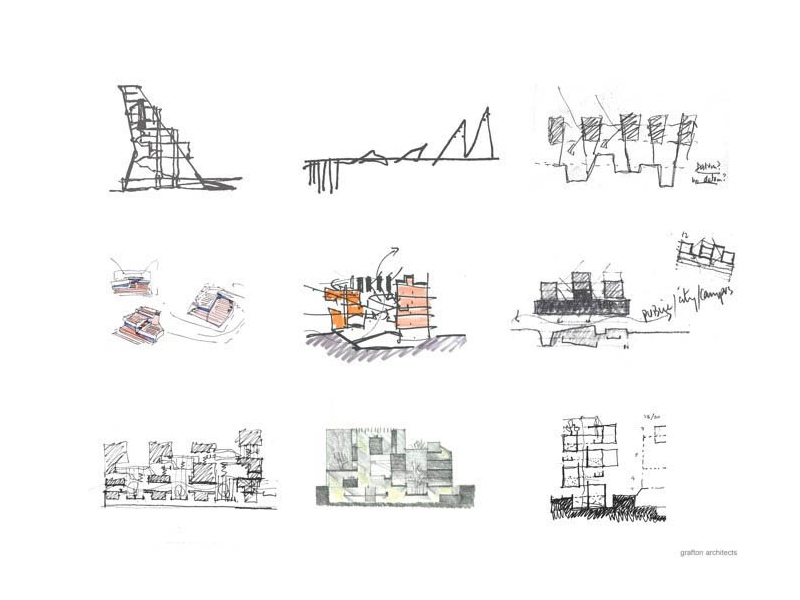

In one of your lectures you explain your Dia- grams of Intent as “a secret enigmatic symbols that form a part of DNA of each project”. Do they appear at the beginning or are they the result of something achieved during the process, after all do procedures?

It is always different. Sometimes it happens early on, where a sketch captures something and because we know there is something in there, we try to translate it into architecture. And other times, it comes from after a lot of struggle, where everything seems foggy and confusing and we question ourselves a lot until reaching to this sketch, this kind of hieroglyph, that captures the core of each project. It is amazing how essential these sketches can be, as a form of communication between us, and between the outsiders.

Are these sketches produced by both you, and Yvonne?

Yvonne and myself produce them, but other people in the office also produce them. The ones that are published and credited to us are our sketches. So, many of them come from us but very often a sketch that someone in the office draws becomes also part of the process.

Going back to Group 91, how did it close-up?

It is very interesting. I remember young architects say- ing to me – you really failed because Group 91 finished – but we had never thought about it as being something that would go on. We felt that it was something of magical that came together and was completed, because everybody made a project. I suppose, things happen naturally.

A built project?

Well, not everybody actually. One of the architects, McGarry Ni Eanaigh, unfortunately didn’t because they were doing a bridge across the river Liffey and that project stopped. It was a tragedy. But effectively, people made their projects and when the project was done everybody went their own way. Although we have spoken about collaboration, and some people within the group have collaborated since, I think if there were certain opportunities it could work.

Again, I suppose you have to believe when things happen naturally. It’s hard to force collaboration. And in fact, we tried once or twice to collaborate with people with whom we thought we had common ground, and we do, but then the chemistry of working together was quite difficult. So it doesn’t always work so easily. It depends on how big the project is and how independent you can be and respect egos.

And boundaries, I suppose. Understanding where those boundaries touch and distance themselves. How was the working space of Group 91 organized? Was there a physical space or did each practice work independently?

We worked closely together, meeting once a week. We divided the area into different parts and each practice had to make proposals for those areas and then we worked on how to stitch them together. We reviewed each other’s work. Which was very painful, at times, because you know your peers; you respect your peers and so, criticism from your peers is painful and some people are more fluent than others and make beautiful drawings and some people are slower and make not so beautiful drawings. There was always this balance to be held. In the end, a number of collaborators undertook the mission of bringing together our proposal, in terms of format and graphical representation. It was important that it looked like one project.

Exactly. So here we reach the issue of authorship. How was this preserved?

I don’t think, at the time of the competition, author- ship was an issue because everybody had made a huge contribution and, we really did feel everybody owned that project. No one individual or no ones office owned that project. There was a very strong sense of it being a team project. Everybody invested their energy at a same level and everybody made a very important contribution. So, there was no issue of authorship, really. Well, I certainly didn’t feel it. It was Group 91 project and that was it. And then, of course, when the projects were completed, the authorship became very clear. Here, we were dealing with individual projects after the competition phase.