I am the theater: An account of the paradoxical layers of invisible forces of Western oppression.

Viola Ago

Several days earlier than the legal permit allowed, at 4:30 a.m. on May 17, 2020, the National Theater (Albanian: Teatri Kombëtar) located in Albania’s capital, Tirana, was demolished by police bulldozers under the orders of the Albanian government. This demolition, which was proposed by prime minister Edi Rama in 2018 (and which he attempted as […]

Several days earlier than the legal permit allowed, at 4:30 a.m. on May 17, 2020, the National Theater (Albanian: Teatri Kombëtar) located in Albania’s capital, Tirana, was demolished by police bulldozers under the orders of the Albanian government. This demolition, which was proposed by prime minister Edi Rama in 2018 (and which he attempted as early as the year 2000 during his time as the city Mayor) had been met with fierce resistance from some of the theater’s artists, political activists, civilians, and members of the opposition.1 Mandates from politicians to demolish historically significant buildings is not uncommon in post-civil war Albania.2 The Pyramid of Tirana (Albanian: Piramida), a former museum designed by Albania’s tyrant ruler Enver Hoxha’s daughter and her husband, suffered a similar story and almost a similar end.3

Demolishing of the National Theater Tirana May 17, 2020. PHOTO: Nikola Đorđević, Emerging Europe.

The typical narrative—or rather propaganda—to support demolition proposals for historically significant buildings is typically based on two conditions: said building is deteriorating and its presence is reminiscent of a painful past. Though both statements contain factual truths, the narrative is woefully absurd and even paradoxical. The state-owned Pyramid and National Theater are in fact deteriorating because the government has consistently failed to prioritize the maintenance of these structures. It is also true that each building register times that dilapidated the land and tormented its people: the 50-year long tyrannical totalitarian communist regime of the second half of the 20th century in the case of the Pyramid and the Italian fascist colonization at the start of World War II for the National Theater. However, both buildings are prominent cultural institutions regardless of the conception and construction of the built structures. With that in mind, I can’t help but question the motivations behind Rama’s unwavering will—and the measures he took—in this recent case to demolish the National Theater. Putting aside the financial incentives exposed in his blatant corruption schemes 4 (rather normal behavior for a lot of government officials), let’s instead trace the invisible forces that propel the desire for such large-scale and arguably unlawful demolitions.

The flagrant5 demolition of the National Theater materializes a deteriorating and increasingly polarized relationship between the public and the state. There are two distinct (and by association paradoxical) instantiations of oppression that have been infused in the general public and the state. Before offering a thought experiment for creative discourse, it’s important to note the most peculiar aspect of the situation: for a people that has been occupied, colonized, invaded, ruled with an iron fist, isolated from the world, stripped of more than half of its collective GDP overnight, ethnically cleansed—to name but a few of its catastrophes over the last 600 years—how is it possible that during the demolition of an institution built during the fascist colonization, the same people placed themselves physically inside the building in a final attempt to protect it?6 Are they still under the lure of its original western promise (a Stockholm Syndrome of sorts)? Or do they occupy a different conceptual and lived plane than that of their government and the complacent part of the community?

Protests over national theater demolition. Associated Press

Part 1 – The Paradoxical Axis

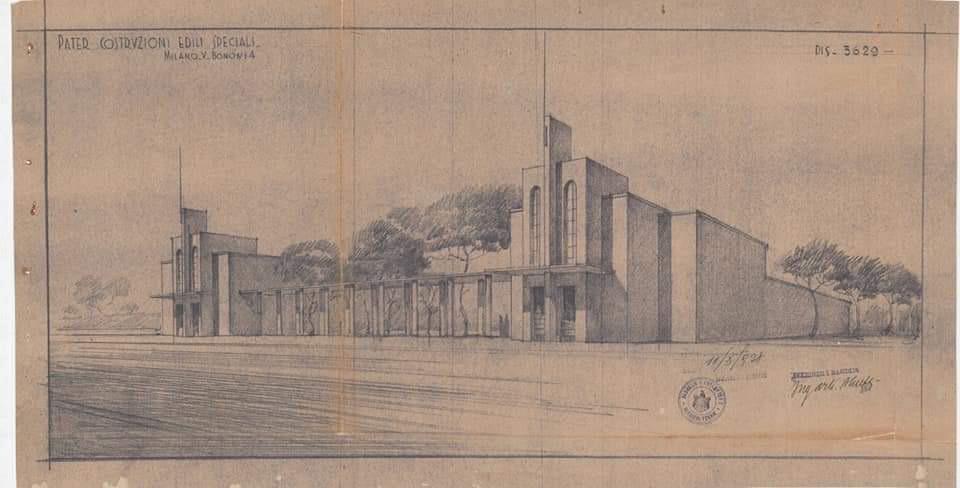

Designed in 1938 by Italian Architect Giulio Berté (during the Italian fascist era under Benito Mussolini) and built by the Pater Costruzioni Edilizia construction company in 1940, the National Theater was one among several notable buildings that were part of a new urban planning trategy designed in the style of Italian Rationalism7. Italian rationalism was exercised in Italy and imposed on most of the Italian Fascist Party’s colonies (including Somalia, Libya, and the Dodecanese Islands)8.

In Albania, it was particularly easy to enforce this new design-paradigm because it offered an ordered, modernist aesthetic to an ancient and unruly land 9. Enter oppression instantiation 1. The intricate history of Italy’s occupation of Albania and the handover of all building projects exclusively to Italian construction companies is deep and lengthy (to do it justice, you would have to start with the Roman colonization of Illyria 230 BCE–169 CE10). Again leaving power and financial gains aside, there are two primary circumstances that permitted the rise of Italian Rationalism in Albania that are important to the question of oppression, and more particularly, the more dangerous and detrimental ones, such as the invisible and unforeseeable ones—deeply rooted in the psyche and body. For one, this occupation was successful, sudden, and bloodless because the strength of the Albanian Resistance Forces was waning—they had been fighting for independence in various capacities since 1479. In addition, the public was indoctrinated to believe that architectural and urban designs by modern Italian architects and planners promised a speedy one-way ticket to the “West”. Allow me to rest and expand on the sentiment for another moment: One of the most ancient tribes of the Balkan peninsula, who speak one of the oldest languages in the world and who have millenia of historical, cultural, and traditional richness, discounted their capacity to contribute to the “West” (or to reside in the margin for that matter) at the turn of the 20th century because they had fallen so behind in industrial power from exhausting all resources towards fending off foreign invasion for almost 500 years. That’s not the worst part.

Enter oppression instantiation 2. The most painful part of this continuous history is that, analogously, present-day Prime Minister Edi Rama continues to discount the Albanian people and their seemingly inexhaustible culture by demolishing and completely erasing a performing arts institution that had supported the accumulation of intellectual and artistic capital in the country for the last 80 years. In eerily similar details, Rama justified the demolition of the National Theater by replacing it with a new theater designed by Danish corporate firm BIG Architects (including a hidden agenda for the construction of three or four private luxury residential towers on the same property11) in what he said was going to be “[A]nother cultural destination of European proportions.” 12 Make no mistake that Rama’s “European” refers to a Europe that aligns with a neo-liberal image of the West exclusively.

Under the same narrative, other westerns architects whose projects have been endorsed and commissioned by Rama’s government include: Italian based Archea Associati, Belgium based 51N4E, Netherlands based MVRDV, and Austria based Coop Himmelblau. Most of the proposals/built works from these commissions offer at best fleeting notions of contemporaneity with their corporate aesthetics and are purely capital-driven, neo-liberal nightmares. Rama’s fascination with “European proportions” displays a complex set of desires (shared by many non-western populations), including the desire to belong to the Occident regardless of the price-tag13 and to eventually be accessioned to the European Union. To reiterate, invisible forms of oppression are powerful and deeply ingrained, and they create these catastrophic conditions where one attempts to escape a previous occurrence of coercion by exactly using the same force (i.e. using the same oppression narratives of the past that the present is trying to escape).

National Theatre of Tirana. https://www.tiranatimes.com/?p=146016

Part 2 – Insights for Creative Discourse

“‘If Europe only understood,’ he says (and it should be remarked that he rarely, if ever, classes himself as European)— ”

Edith Durham, 1905, reporting from her trip to the Balkans on behalf of the Macedonian Relief Committee.14

Reducing the existence and importance of the National Theater to one characteristic—the fascist ideologies of the time period it was built in—is in and of itself oppressive, and it can even be aligned with racist and xenophobic tactics of western right-wing extremists. It is indisputable that this institution carried an inestimable amount of cultural cache for its people. Its inflammatory demolition caused demonstrations to erupt instantly at the realization that—among other things—history repeated itself in top-down fascist-like manners reminiscent of those from 80 years ago. For the people, this is not simply a fight for the theater, but also a fight for democracy itself15. Yet, Rama’s and city mayor Erion Veliaj’s concern for the people was nonexistent partly due to their unwavering conviction that they are forging the path towards a progressive future; there is a strange we-know-best tone emanating from their government.

Slogans such as “Unë jam teatri” (translated: I am the theater) and speeches from the various continuous demonstrations by artists and activists describe a unique relationship to the physical building, its space, and its associated cultural collective. Sentiments such as these—being the theater, feeling that the theater is part of a person’s body, and associating the birth of many artistic and creative institutions with the physical presence of the building16—are extremely captivating from an architecture perspective.

New Tirana National Theater, BIG.

Contemporary thinkers such as architecture critic Sylvia Lavin and political theorist Jane Bennett have theorized extensively on culture, surrounding, and being/becoming in the world through affective experiences and phenomena. In her Architecture in Extremis article, Lavin argues for a rejection of standardized contemporary architectural proposals in favour of “temporal flows” and “architectural ambiances.”17 If Lavin saw BIG’s proposal for the new National Theater—shaped like a bowtie, placed on a flat ground, oriented in alignment with its property lines, represented in typical contemporary materials, and rendered with predetermined behavior of programmed space—she surely would be dismayed by it. I would argue that her call to allow objects and participation to occupy interior space or architecture at large can generate new productive ideas. She suggests the method of “churning” for architectural alternatives. To be specific, Lavin argues that taking existing things18 from the past and putting them on display again out of turn—a non-ordered, cyclical return of things—can be a form of active resistance against the standardized architectural projects that emerge out of a lineage of embedded and inherited predispositions (modern, post-modern, neo-modern, etc.).

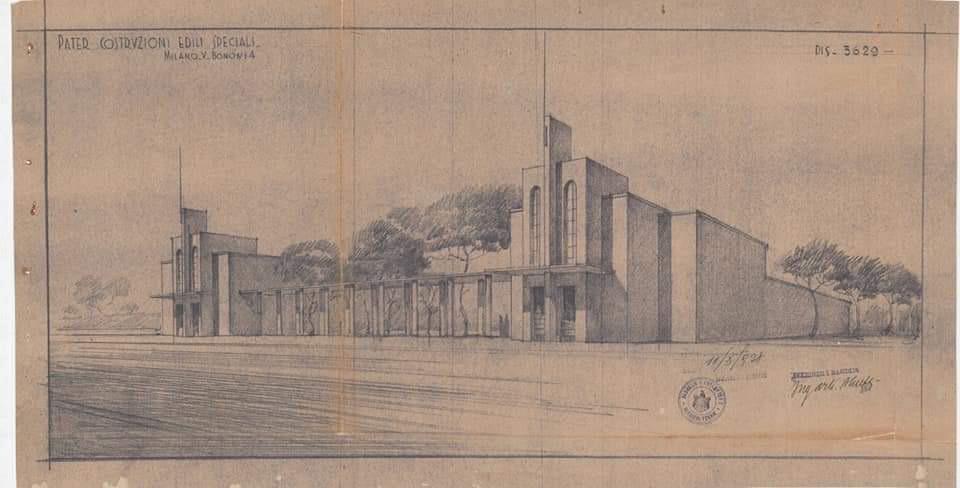

Debris from the original National theater

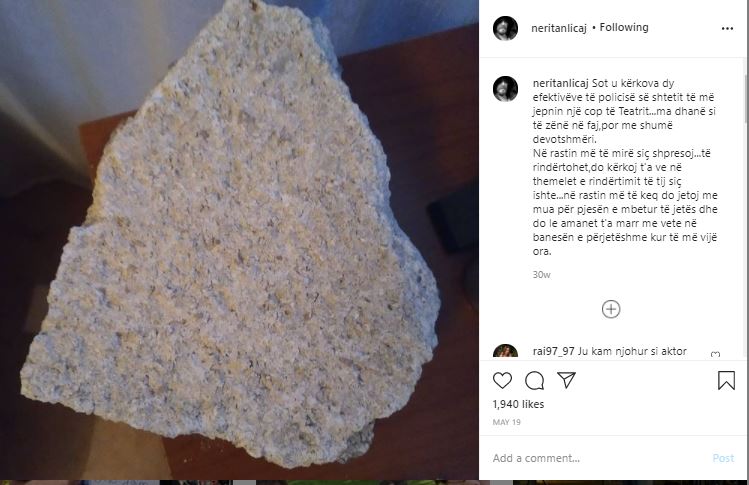

From another point of view but in alignment with Lavin’s thinking, Bennett, in her recent book Influx and Efflux: Writing Up with Walt Whitman offers an alternative understanding of the world through the phenomena of atmosphere. She argues that all material things make up an atmosphere filled with forces and actants whose primary mode of communication is not just the human language, but rather lyrical and haptic, and by extension, indeterminate and non-ordered.19 In Bennett’s proposal, by flattening the material structure of humans, animals, plants, and minerals, meaning and value are then not only human, but rather they reside in a shared material continuum. Such is also the sentiment from the artists and activists that have defended their theater with their bodies. I am the theater. Even after the demolition, when the built structure could no longer be saved, the theater was not lost; it continued to live with the people who felt its presence. A piece of debris carries its essence, such as the one requested by performance artist/actor Neritan Liçaj after the demonstration.20

With these parallels in mind, it seems that the theater, the people, and history suggest a context that was primed for a productive, invigorating, and refreshing yet-to-be-known architectural alternative: one that did not rely on mimicking the West and, in doing so, repeating atrocious cycles of human and civil injustices. This was a perfect case where with some recognition of self-worth, conversations with practitioners, critics and theorists, and the involvement of the people that occupy the building with such “lyrical force,”21 a new model could have emerged. Sadly, history found a way, yet again, to coldly betray our present.

Parting Thoughts:

The erasure of the National Theater is emblematic of the desire for Rama’s government to suppress the intellectual and artistic wealth of the people of Albania. In the pursuit of liberation from such modes of coercion, the Albanian people reacted strongly to the demolition proposal but to no avail. As previously mentioned, the maintenance neglect had admittedly left the theater in a rather deteriorated state. But in the wake of such destruction, negating the binary narrative of old vs. new, or east vs. west might offer a way out of this oppression. Following Lavin’s and Bennett’s calls for resistance and non-human centric lenses, a collapse might occur: a collapse that encompasses binaries by stripping them from their previous value systems—the East and the West, the old historical theater and new contemporary interventions, the old rough algae-binding cement and the new shiny synthetic siding, the dirty and the clean—into a flattened continuum that creates an atmosphere of events and indeterminate phenomena. I am the theater.

1 Monika Kryemadhi, a Member of Parliament, leader of the Socialist Movement for Integration Party (Albanian: Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim, or LSI), wife of the current President (head of state) was one of 30 people detained at the demonstrations on May 17th, 2020. See: Dellanna, Alessio. “Wife of Albania’s President Detained during Protest.” Euronews, 18 May 2020, www.euronews.com/2020/05/18/wife-of-albania-s-president-detained-during-clashes-over-national-theatre-demolition.

2The Albanian civil war was primarily caused by the collapse of the ponzi pyramid schemes in the late 1990s.

3 Nikoli, Fatmira. Albania Activists Lament Demolition of Hoxha Pyramid. 28 May 2018, balkaninsight.com/2012/05/30/albania-activists-lament-demolition-of-hoxha-pyramid/.

4On May 8th, 2020, the Albanian government transferred the land ownership of the theatre from the Ministry of Culture to the Municipality. This transfer signified that public land could now legally be used to develop private and commercial projects. See: Taylor, Alice. “Albanian Government Hands Ownership of National Theatre Land to Municipality of Tirana – Exit – Explaining Albania.” Exit, 10 May 2020, exit.al/en/2020/05/09/albanian-government-hands-ownership-of-national-theatre-land-to-municipality-of-tirana/.

5 Çela, Lindita, and Gjergj Erebara. “Zbulohet Projekti i ‘Fushës’ Me Afro 90 Mijë Metra Katrorë Kulla Dhe Teatër.” Reporter.al, 27 Jan. 2020, www.reporter.al/zbulohet-projekti-i-fushes-me-afro-90-mije-metra-katrore-kulla-dhe-teater/.

6 According to Romeo Kodra, Nerital Liçaj was inside the building during the demolition. Liçaj and other supporters and activists had been staying in the theater on 24hr cycles in order to protect it from demolition. See: “Cynicism and collaborationists in arts. Destroying monuments and art in Albania.” presentation in the framework of “Friday 17th: Two Months Without Teatri Kombëtar”, organized by Forum dell’Art Contemporanea Italiana, 17/07/2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-AGaM2nDfvc&t=7358s

7 Mandates for a new urban plan had been long-in-the-making and had started after World War I with mutual relations between Musolini and the Albanian king at the time, King Zog. See: Peter, Tase. “Italy and Albania: The Political and Economic Alliance and the Italian Invasion of 1939.” Academicus International Scientific Journal, vol. 6, 2012, pp. 62–70., doi:10.7336/academicus.2012.06.06.

8 Fuller, Mia. “Building Power: Italy’s Colonial Architecture and Urbanism, 1923-1940.” Cultural Anthropology, vol. 3, no. 4, 1988, pp. 455–487.

9 The new Urban Plan divided the city into old and new.

10 Durham, M. Edith, and Robert Elsie. Twenty Years of Balkan Tangle. Centre for Albanian Studies, 2015.

11 Let alone the fact that he flagrantly transferred land ownership rights to the municipality without following constitutional law. The backdoor deal with Fusha SHPK (speculated such that Fusha agrees to build the new Theater at no cost if they allowed them to build luxury towers on the theater’s) was not unlike King Zog’s with Musolini’s government and trade business (and banks). See: Kodra, Romeo. “Architectural Monumentalism in Transitional Albania.” Studia Ethnologica Croatica, vol. 29, 2017, pp. 193–224., doi:10.17234/sec.29.6.

12 Block, India. “Protests in Tirana Ahead of BIG Project as Albanian National Theatre Demolished.” Dezeen, 21 May 2020, www.dezeen.com/2020/05/19/protests-tirana-ahead-big-albanian-national-theatre-demolished-news/.

13 It would take another essay to describe the geo-political intricacies of Albania as the tug-of-war land between two giants: the Orthodox/Catholics to its northwest (the Occident) and the Islamic Turks to its southwest (the Orient, the Near East).

14 Durham, M. E. The Burden of the Balkans. Forgotten Books, 2017.

15 A lot of the demonstration chantings were “Liri, Demokraci” which translates to “Freedom, Democracy”. This chant has a long and weighted history in the country’s political transitional periods.

16 Taylor, Alice. “Albanian Government Hands Ownership of National Theatre Land to Municipality of Tirana – Exit – Explaining Albania.” Exit, 10 May 2020, exit.al/en/2020/05/09/albanian-government-hands-ownership-of-national-theatre-land-to-municipality-of-tirana/.

17 Lavin, Sylvia. “Architecture In Extremis.” Log, no. 22, 2011, pp. 60. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41765708. Accessed Aug. 2019.

18 Thing is used here in an anthropological sense such that items, objects, ideas, resist their definitive boundaries. This way, a thing can be material or immaterial, active or passive, and can be used to describe essence that can flow from one form into another.

19 Bennett, Jane. Influx and Efflux: Writing Up with Walt Whitman. Duke University Press, 2020, ch 2, 8.

20 Neritan Liçaj requested a piece of rock from the theater after the demolition. He announced publicly that he will attempt to place in the foundations of the new theater if things go according to his plans. Otherwise, he will request in his will to be buried with the rock in his (translated from alb.) “forever-after place of living when my time comes”.

21 Bennett, Jane. Influx and Efflux: Writing Up with Walt Whitman. Duke University Press, 2020, pp 74-77.

Viola Ago (b. Lushnjë, Albania) is an architectural designer, educator, and practitioner. She directs MIRACLES Architecture and is the current Wortham Fellow at the Rice University School of Architecture. Recently, Viola was awarded the Yessios Visiting Professorship at the Ohio State University Knowlton School of Architecture and the Muschenheim Fellowship at the University of Michigan Taubman College of Architecture. Viola earned her M.Arch degree from SCI-Arc, and a B.ArchSc from Ryerson University. Her written work has been published by Routledge and Park Books, as well as in Log, AD Magazine, Offramp, Acadia Conference Proceedings, JAE, TxA, Architect’s Newspaper, and Archinect.