To Step Light on e/Earth

Thiago Benucci

The critical consciousness about the causes and effects of the Anthropocene can unsettle not only the extensively urbanized mode of dwelling on this planet, but also the onto-epistemic assumptions that structure the discipline of architecture. In short, the root-idea of Nature as a free resource available to the exceptionality of human Culture. However, facing the […]

The critical consciousness about the causes and effects of the Anthropocene can unsettle not only the extensively urbanized mode of dwelling on this planet, but also the onto-epistemic assumptions that structure the discipline of architecture. In short, the root-idea of Nature as a free resource available to the exceptionality of human Culture. However, facing the urgent need of some kind of reaction to climate emergency, architecture, perhaps more than ever, requires redefinition.1 As proposed by Donna Haraway, “we – all of us on Terra – live in disturbing times,” and as a “necessary resurgence,” our “task is to make trouble, to stir up potent response to devastating events, as well as to settle troubled waters and rebuild quiet places.”2

Nonetheless, a response to the Anthropocene from within the practice of architecture involves a kind of a paradox, the “paradox of action.”3 On one hand, the challenges of turning away from the hegemonic practices and assumptions in architecture can hold in check the possibilities of action by the project (the main tool in the architect’s tool box), construction, or even the contract. On the other hand, action is necessary because it is necessary to do something. After all, as Greta Thunberg would say, “I want you to act as if the house was on fire, because it is.”

Against the state of paralysis, possibly caused by this kind of paradox, it is necessary to stimulate new forms of “response-ability,” as proposed by Haraway.4 In this short essay, I present a mere glimpse of what seems to me as a fertile form of cultivating response-ability based on the idea of lightness. This idea emerges from my collaboration with the Yanomami people from the Marauiá River (Amazonas, Brazil); and also with my understanding of lightness as a fundamental aspect of the traditional and contemporary spatial practices of the indigenous people of Lowland South America. Through this perspective, then, I raise the question of how we – architects – can learn with these practices in order to radically rethink the hegemonic architectural learning and doing.

Walking in the forest with Claudio Yanomami, from the Pukima Cachoeira village, at the upper Marauiá River region. The Yanomami consider themselves as the “people of the forest” (“urihiteri pë”) and a considerable part of the knowledge that I acquired with the Yanomami people comes from walks in these forest trails. All pictures presented in this essay as 35mm analogue B&W diptychs are mine, from my last trip to the Marauiá River in 2021, with the companion of Daniel Jabra.

It is widely known that traditional and many contemporary indigenous architectures of Lowland South America are essentially ephemeral, sometimes highly mobile, and built with natural and perishable materials, such as wood, straw, and vines.5 For the same reason, they exceed the monumental-stone-centered comprehension of the colonial and auto-colonial agents – particularly architects and historians – which did not even consider (or considered, historically) these architectures as a valid form of Architecture (with capital “A”). One of the assumptions behind this kind of indifference can be elicited by recalling the Vitruvian principles of firmitas, utilitas, and venustas that structure the classical ideology of architecture. Firmitas, in the sense of “solidity” and “durability,” is precisely what lacks in the kind of architecture presented by the indigenous spatial practices of Lowland South America. However, just like Italo Calvino once wrote, through the “opposition between lightness and weight,” I will “uphold the values of lightness”; not in the sense of “vagueness,” but of “precision.” Or, better said, like Paul Valery (quoted by Calvino), lightness “like a bird, and not like a feather.”6

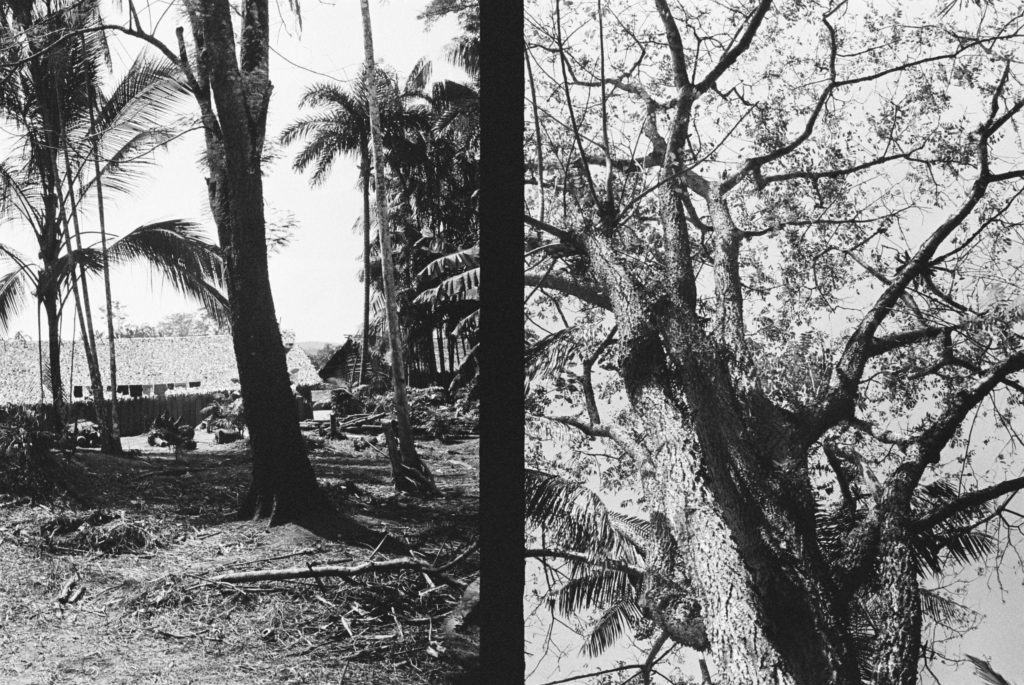

On the left, a village recently built on the banks of the lower river.

As noticed by Sergio Yanomami, from Pukima Beira Village at the upper Marauiá River, during the first of his travels to the megalopolis of São Paulo, it is exactly the weight of this solid and (supposedly) durable concrete constructions that suffocates the e/Earth.7 Asphyxiated by countless apartment buildings, immense viaducts, lengthy highways, and endless kinds of pavements swallowing the soil, it is definitely hard to breathe. Trees have fallen, the e/Earth revenges, and the sky threatens to fall.8 Against this planetary catastrophe to come, Sergio Yanomami questions, why not build like the Yanomami, really close to “the ground”, “low”, “light, wooden, for the earth to try to breathe”?9

On the left, detail of a ceremonially painted wood beam, tied in the main wood structure with vine, and the soot darkened roof of a traditional house, owned by the leader of the Pukima Beira village at the upper river.

From a complementary perspective, it was during a boat trip down the Marauiá River, reflecting on the architectures of the Yanomami people that I understood how it is exactly this transitory way of building and dwelling that make the perishable, imperishable. In other terms, it is through the continuity of the infirmitas (or lightness) that the firmitas (or durability) is composed. Not in terms of a durable or solid materiality, but, on the contrary, it is by stepping lightly on e/Earth that the continuity of this transitory way of dwelling extends itself since ancestral times, transforming itself endlessly with all its vitality, creativity and resistance.10 Against the “religion of civilization” and those who “change their repertoire, but repeat the dance” of “stepping hardly on Earth,” these architectures, on the contrary, “step lightly, very lightly, over the Earth,”11 as “a flight of a bird in the sky” in which, in “an instant after it has passed, there is no trace.”12

On the left, the forest camp that we had recently left on the bank of the river, made of light wood poles tied with vines, and also using the trees as natural poles, something usual in these temporary camps quickly built. On the right, the great Sumauma tree (Ceiba pentandra) seen from the boat while sailing up the river.

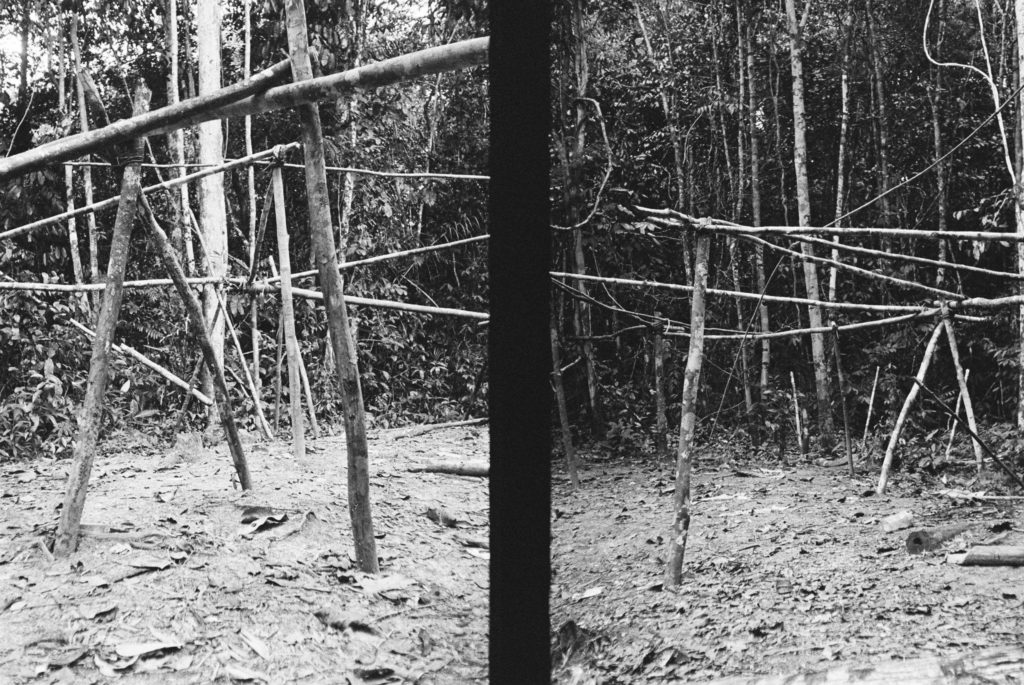

Beyond its light and organic materiality, this transitory way of dwelling is deeply engaged with a dynamic and vital character of architecture. It is fully open to the many movements of life that, varying between moments of more social stability or instability, urges to build, or unbuild, its constructions. Moments of more stability raise the opportunity to build a new house or village. On the contrary, moments of more instability can require to abandon its more durable (yet still organic) constructions, to let them become substrate and then forest again; then it is time to move, to camp in the forest, and to build lighter than before. This variability works as a spatial technology to control the construction’s impact in the forest, the extensiveness and the duration of its architectures. As I argued before, it is through this vital sensibility and dynamic reproducibility that the transitory materiality of architecture can become something lasting, constant, and somehow endless. Or, as I would say, a technology of stepping light on e/Earth.

Abandoned camps in the forest on the banks of the river.

To affect yourself and to really learn with the Amerindian worldviews and its spatial practices is itself a kind of response-ability. In this sense, cultivating response-ability in architecture opens a kind of political-ontological clearing wide enough, as Haraway suggests, “to being for some worlds rather than others and helping to compose those worlds with others.”13 In this sense, an alternative path that cultivates response-ability does not exclude the paradox of action from the scenery, but learns how and with whom to act, react and respond in its presence. Not as a response to the paradox itself, but a response as much to what provoked its intrusion as to its consequences.14

On the left, the Pukima Cachoeira village seen from behind the circle of the houses with cultivated species such as Peach palm (Bactris gasipaes) and Yopo tree (Anadenanthera peregrina). On the right, detail of the top of the Yopo tree, also known as a kind of “house of spirits”.

But how can we expand this ability of learning with the technology of stepping lightly also to our own world – the world of “the people of merchandise,” as postulated by Kopenawa15 –, which is already severely impacted by the extensive human traces on Earth? My response could not be more than a series of propositions to begin to pave a broader architectural technology of stepping lightly. These propositions, however, should be understood more as guidelines to alternative paths, deepening the practice and the reflection based – always – in plural and situated forms of action, rather than to any kind of ready-made emergency escapes.

First, it is time to seriously rethink the root-idea of nature as a resource. To compose with nature and its multispecies entanglements rather than extracting and exploring it in an unidirectional and anthropocenic way. To cultivate more forests, make more kin, and build less cities.16 And even to tense the paradigm of the city, by which – following the critique of the indigenous thinker Ailton Krenak – cannot be seen “other than as a harsh incidence of a human way of inhabiting that could be thought of in other ways, but which has been a sameness for the last, perhaps, 4,000 years.”17 Against this monoculture of the urban, that steps deeply hard on e/Earth, it is necessary to reinvent the city, both conceptually and pragmatically, rethinking the dual opposition between forest and cities, or the separation of Nature and Culture.

In the naturecultural18 forestcities to come, climate-adaptive planning tools will be necessary for the creation of socially and environmentally just multispecies entanglements. Besides that, learning with the indigenous architectures of Lowland South America can also bring to evidence how urgent it is to seriously propose alternatives to the solidified, destructive, and seemingly endless cycles of planetary extraction-construction-demolition. These are the cycles that make our cities, buildings and infrastructures, supports our profession as architects and, at the same time, suffocates the e/Earth. However, it is always time “to being for some worlds rather than others and helping to compose those worlds with others.”19 In this sense, architects can still reinvent themselves by engaging with other worlds. This, however, should not reduce itself by merely reproducing exotic forms of knowledge or construction in foreign contexts, which could, ultimately, reproduce the colonial plunder or even outsource the response-ability to the problems that our own “civilized” world created to others. On the contrary, this change of paradigm in architectural practices can generate and create other forms of acting, collaborating, and seriously engaging within a decolonial and a regenerative perspective.20

After all, as Krenak questions: “Is the only possible continuity of social experience confined to the walls of concrete, iron, cement and glass that our cities have become?”21 Could we imagine other architectures, such as the ones “that prospered in periods of the history of some peoples that gently touch the earth’s body (…) landing like birds?”22 At least, we can start by seriously listening to the lessons from “the forest that breathes, that does not produce garbage, that transpires, that inspires, that gives food, where the roof of the house (…) forms a soft fabric that dialogues with the forest, that dialogues with everything, with the birds, with the rain, with the sun, which has a smell, which has humor and which is a dwelling, a shelter, a house – shouldn’t the city be a shelter?”23 The path of possible responses is definitely lengthy, but there is no lack of pavement to remove and recycle so the e/Earth can finally breathe again. We can start as quickly as a flight of a bird in the sky.