Editorial

CARTHA

During his many years in France, the American sculptor George Grey Barnard acquired a large number of Gothic and Romanesque architectural elements from decayed villages in the countryside. Columns, arches, doors, rooms, and whole buildings made up his growing lot. In 1930, during one of Barnard’s financial crisis, he sold his collection to John […]

During his many years in France, the American sculptor George Grey Barnard acquired a large number of Gothic and Romanesque architectural elements from decayed villages in the countryside. Columns, arches, doors, rooms, and whole buildings made up his growing lot. In 1930, during one of Barnard’s financial crisis, he sold his collection to John D. Rockefeller Jr. The notorious American tycoon, in one of his many philanthropic initiatives, decided to move the collection to the USA and integrate it into the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a sort of sub-division dedicated to Medieval art: the Met Cloisters Museum. From 1934 to 1939, the cloisters of Cuxa, Saint-Guilhem, Bonnefort, and Trie were dismantled and transported to Fort Tyron Park in upper Manhattan. The architect of the new museum, Charles Collens, was given the task of reconstructing the cloisters using only the architectural elements contained within the collection. Through the processes of appropriation and rejection of specific parts of the four cloisters, the assimilation of meanings and constructive principles, and the final conciliation of each piece, Collens created a new model for the cloister, an eclectic assemblage representing an entire European typology.

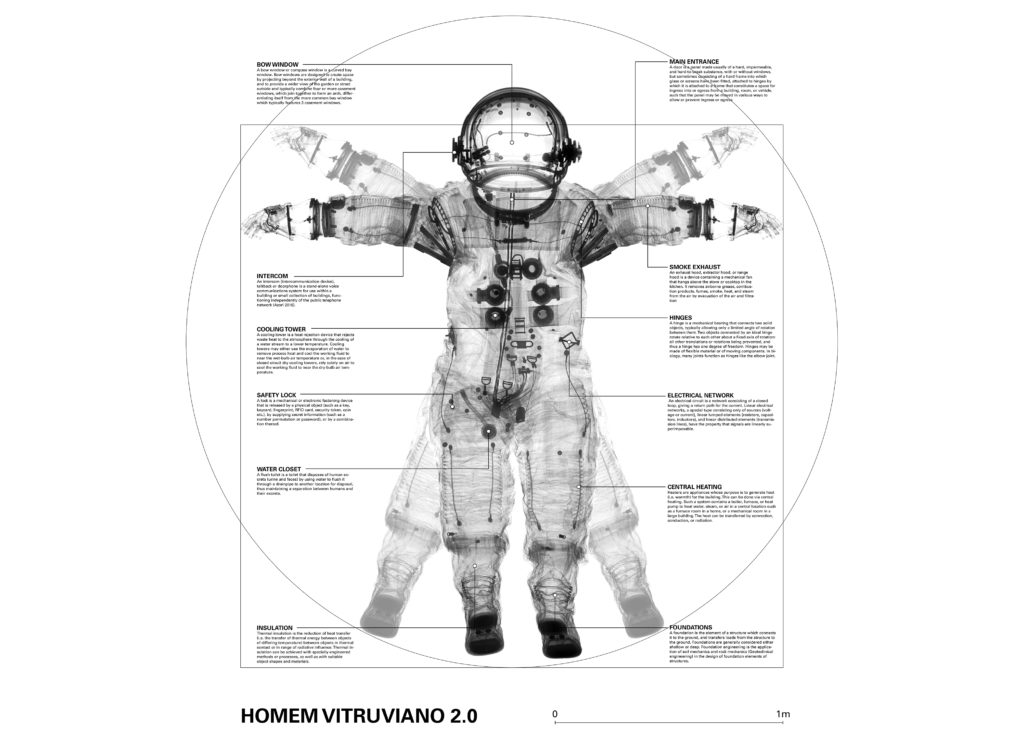

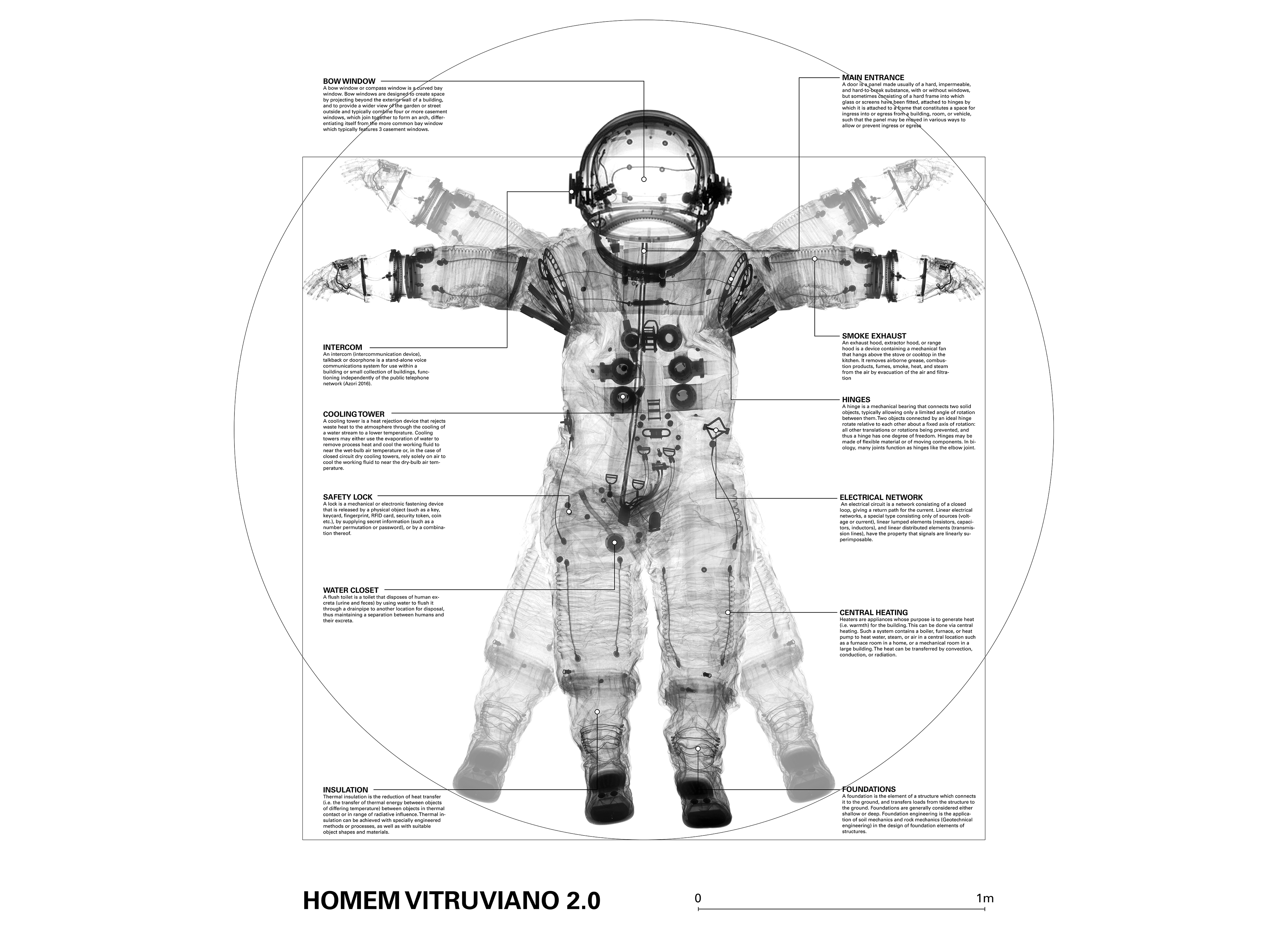

Beyond any criticism regarding the context and ethics of the Met Cloisters, what we wish to focus on is the intention it represents of building a new identity by making use of previously existing elements. The project by Charles Collens seems to corroborate the possibility of making a seemingly direct analogy between the sociological theories of Lacan—among others—regarding the building of one’s own identity solely through the interaction with pre-existing traces and conditions. It also raises questions regarding the role of the architect in the project’s process: is Collens the author of the Met Cloisters?

This fifth and final issue of the CARTHA on Building Identity cycle approaches the questions posed in the four previous issues, each addressing a specific “identity process”—Appropriation, Assimilation, Denial and Conciliation—through a different medium and focusing on projectual answers sourced from an international group of architects.

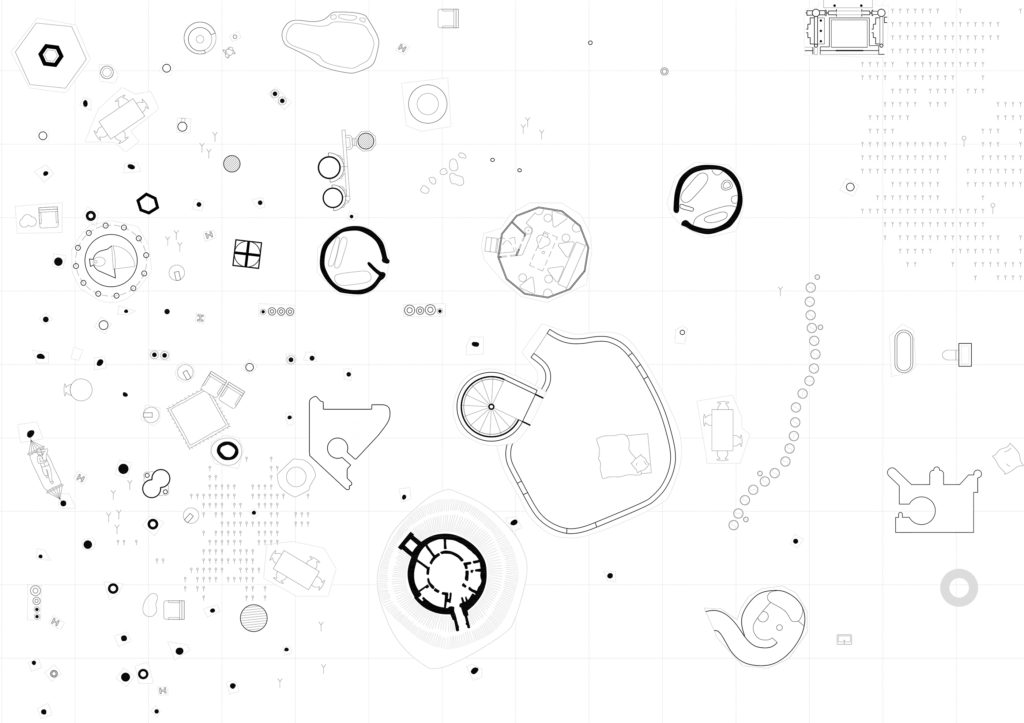

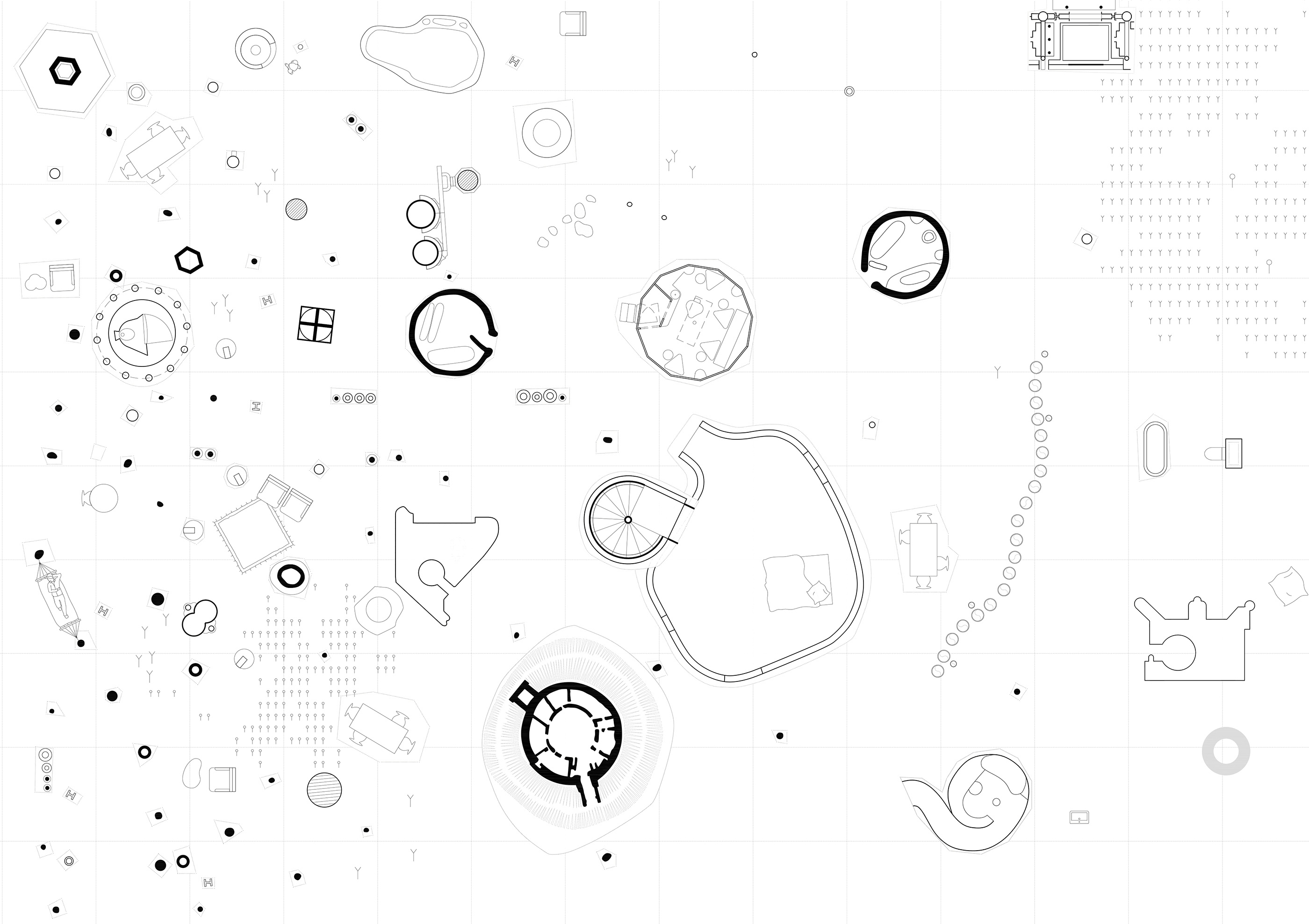

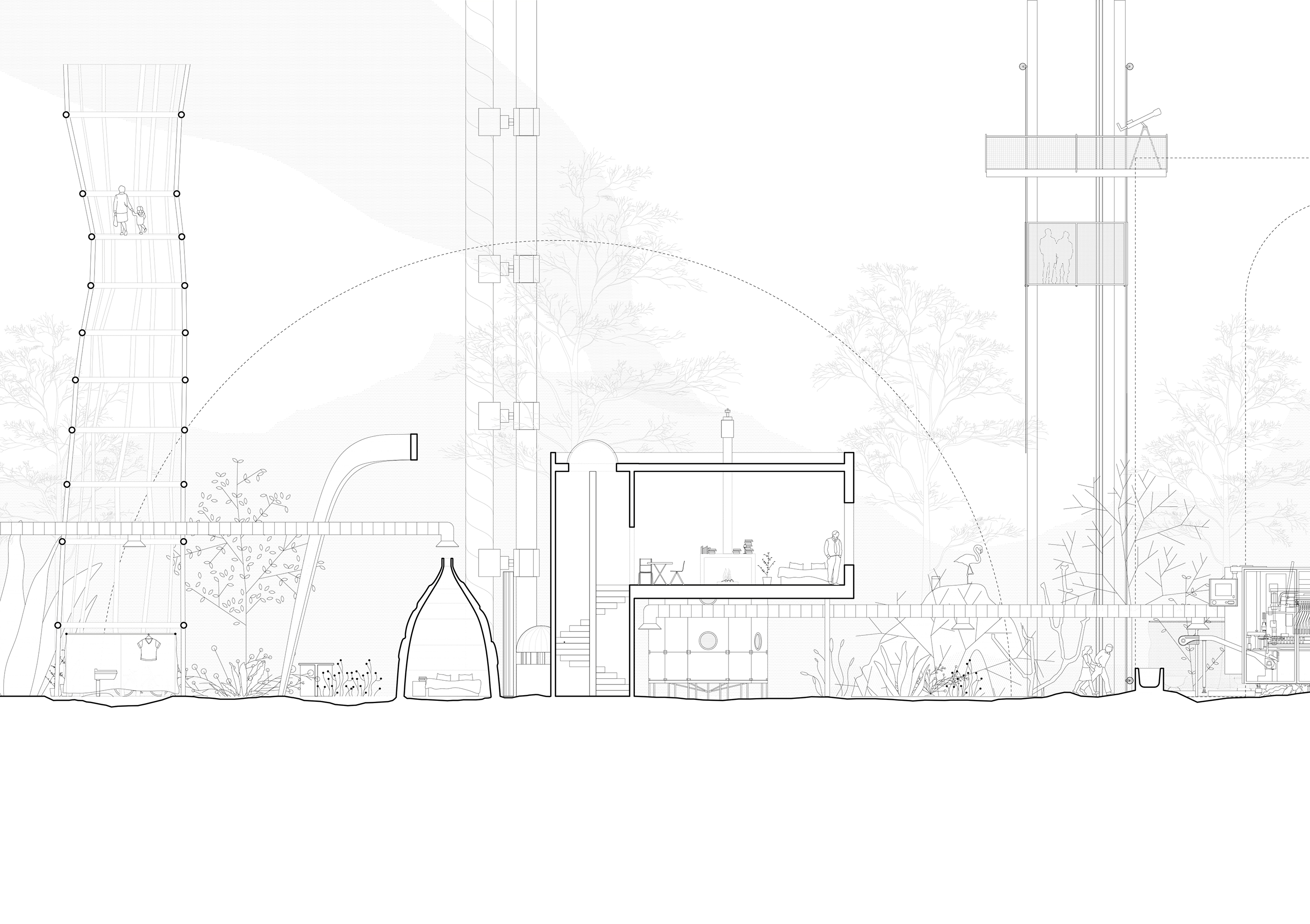

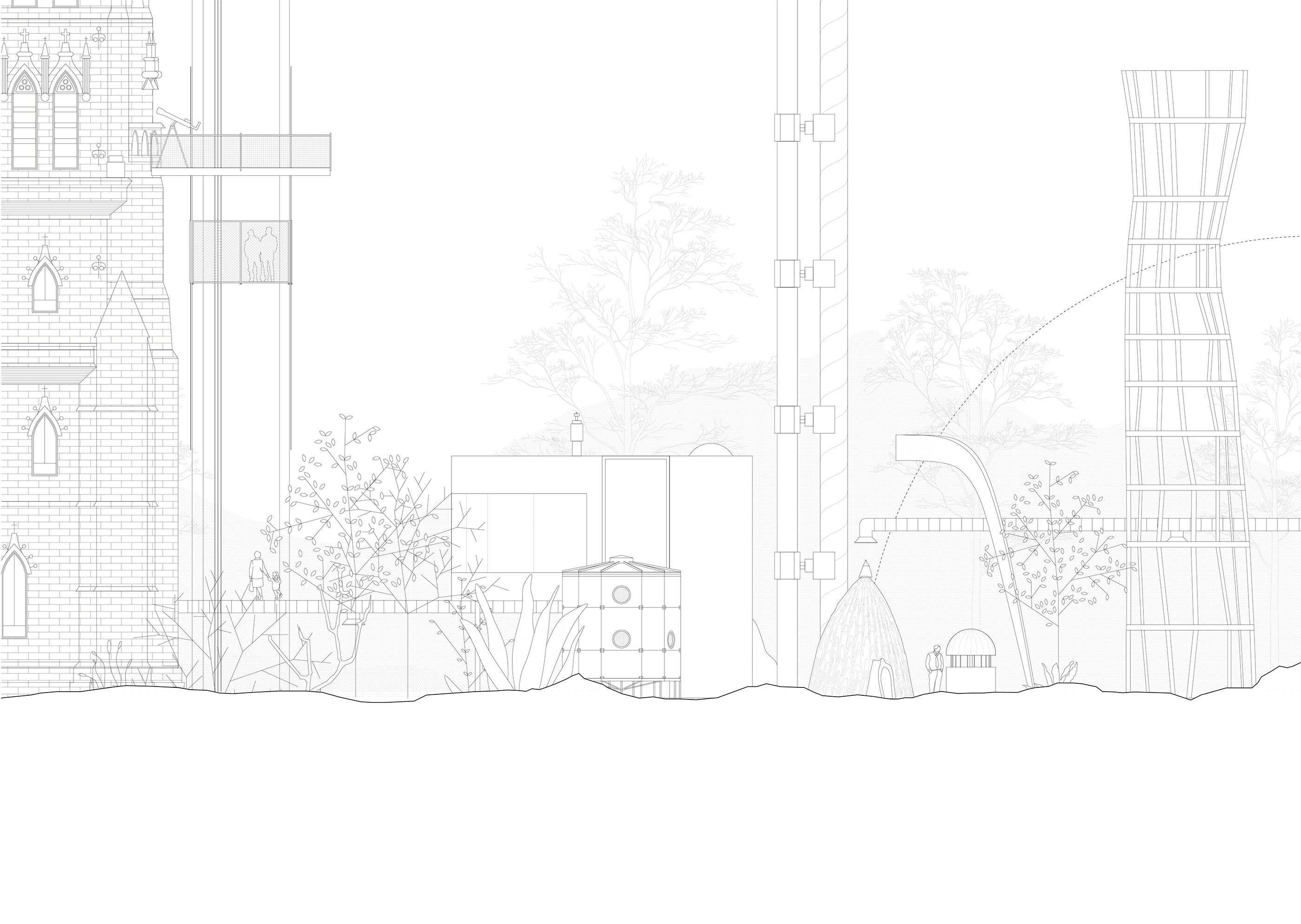

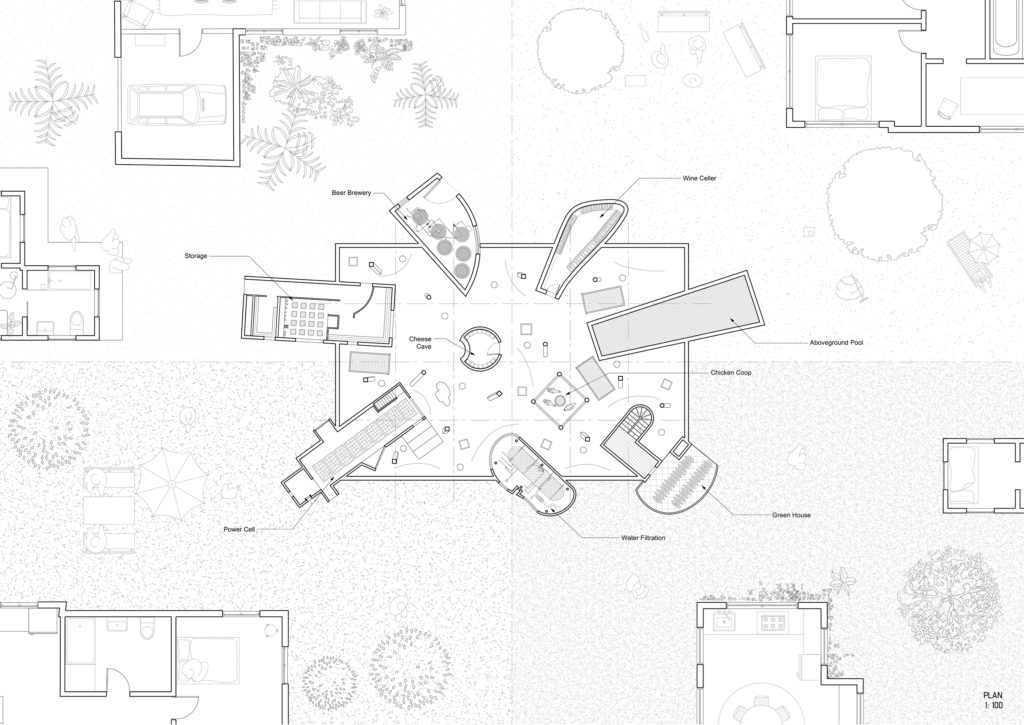

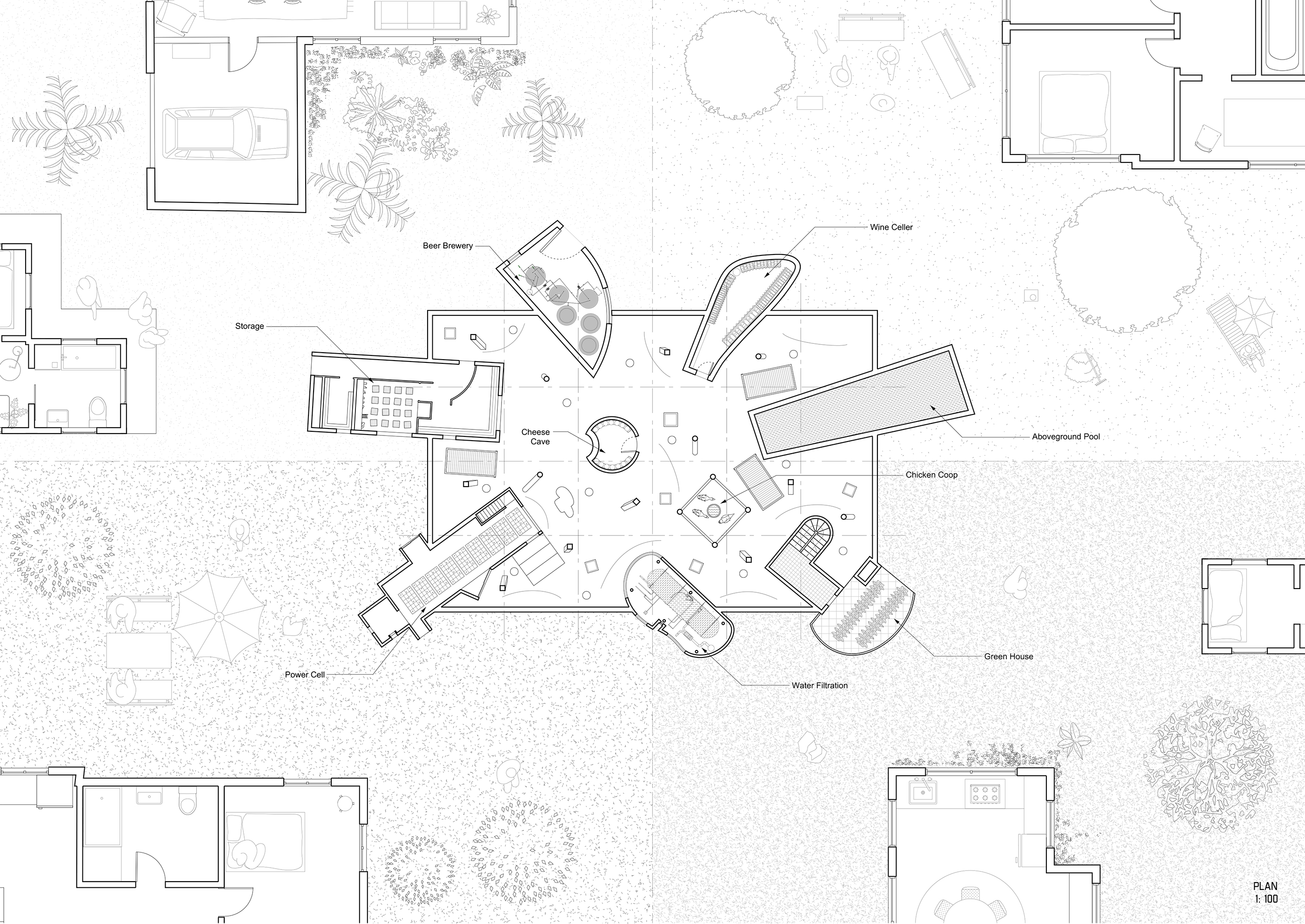

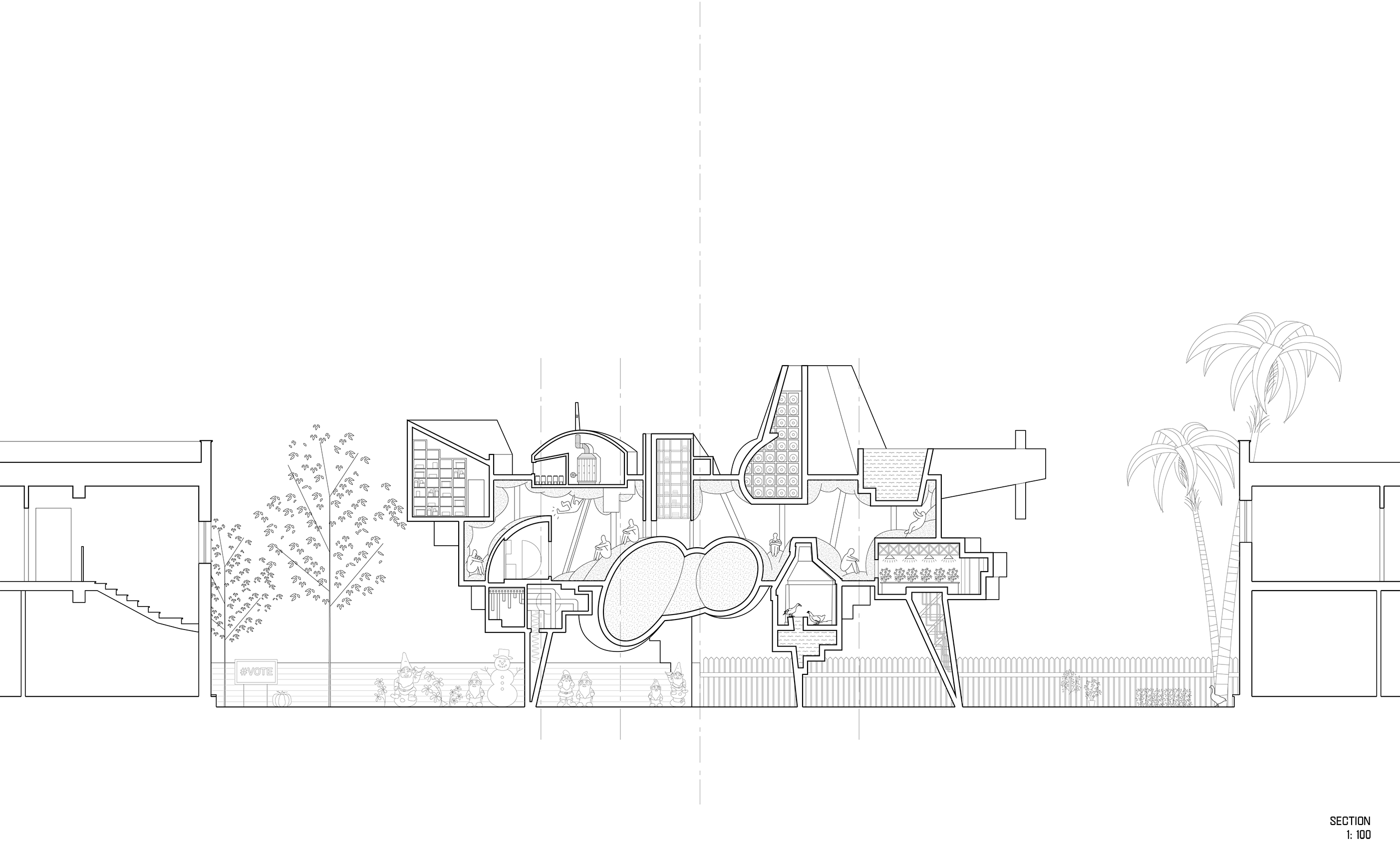

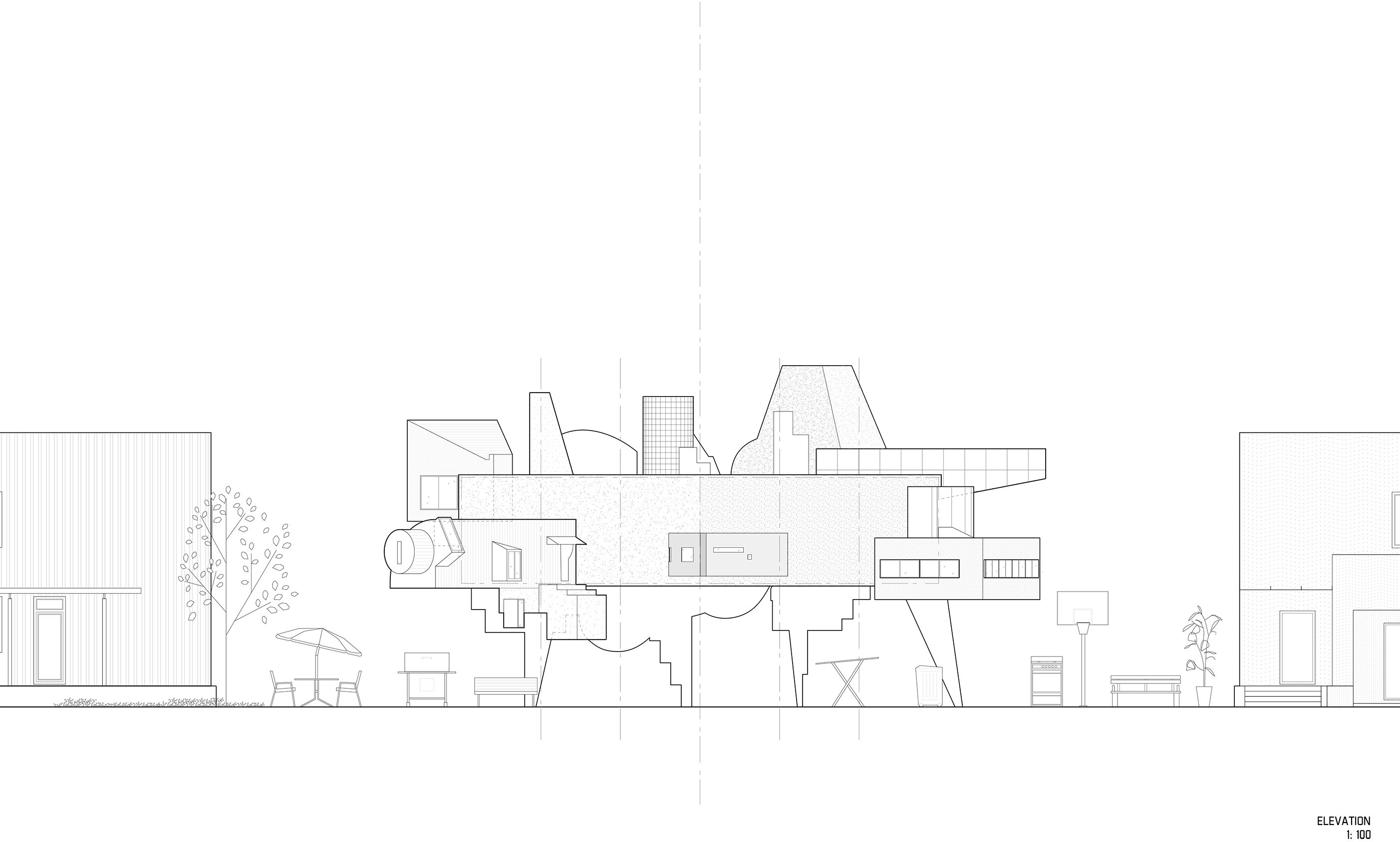

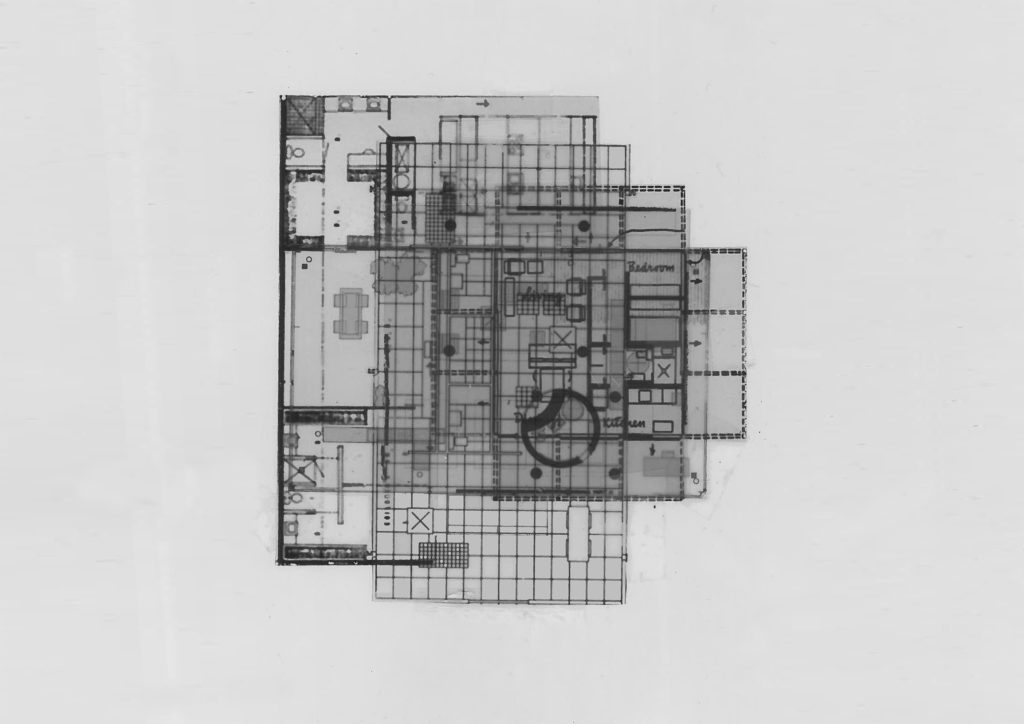

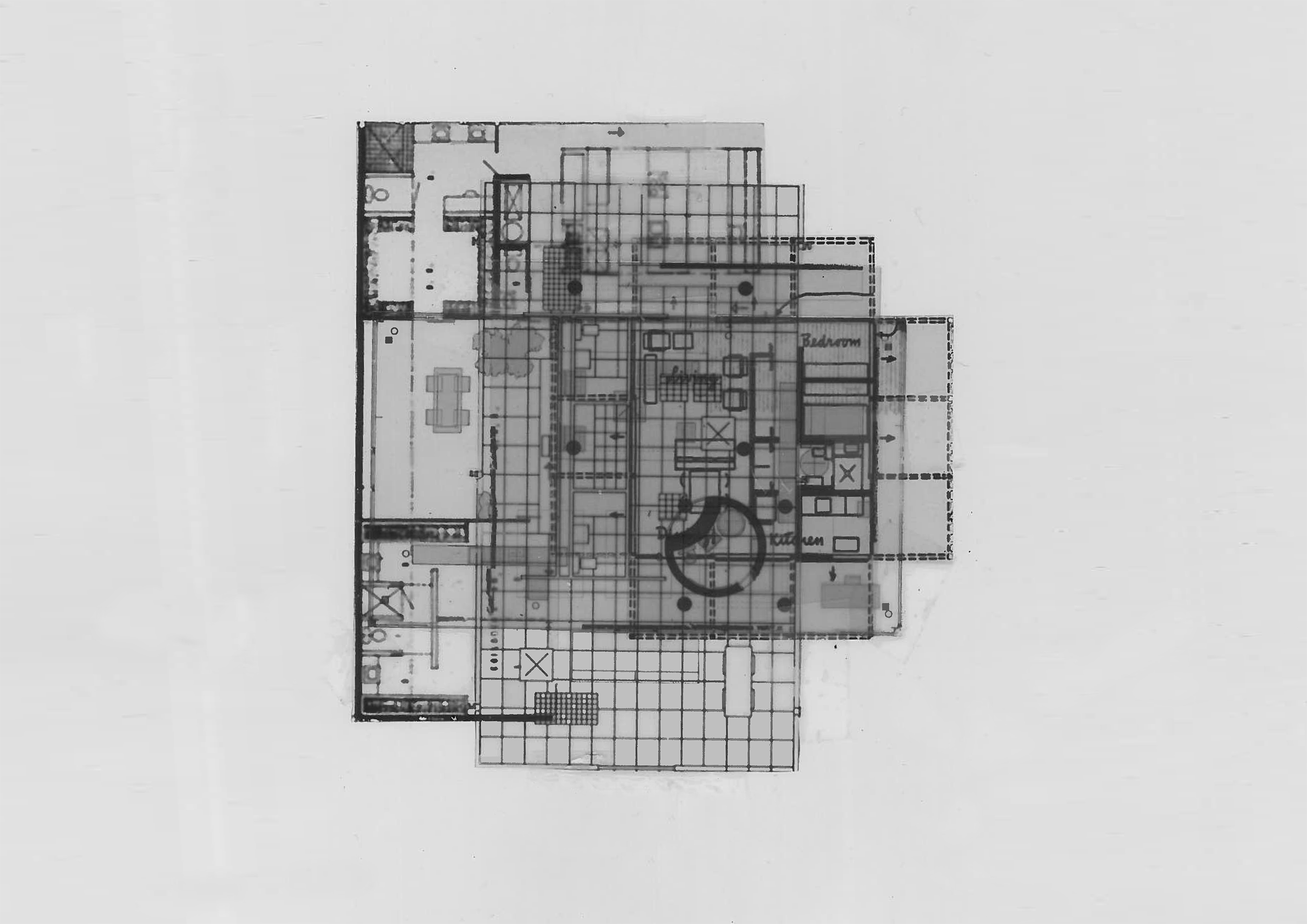

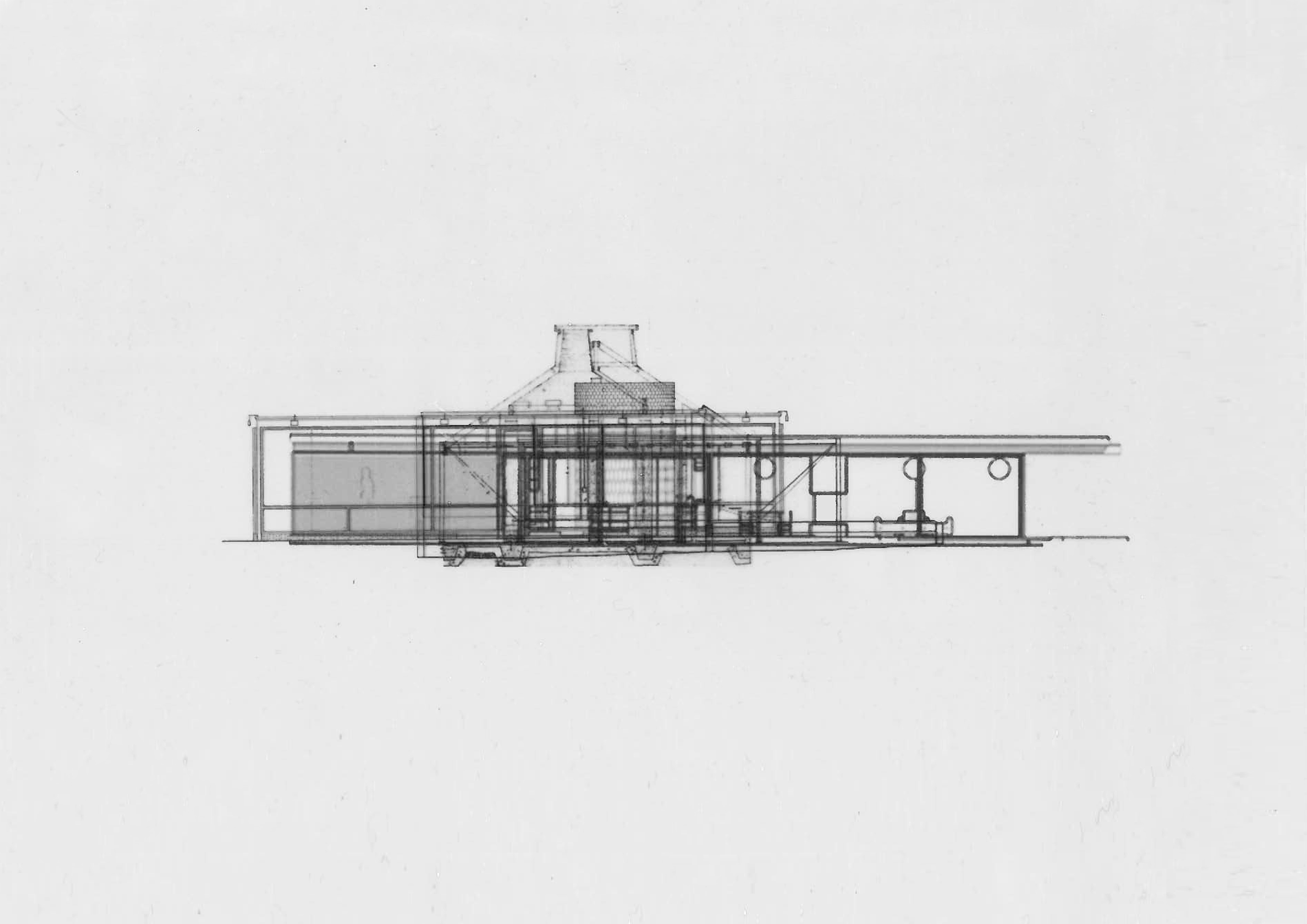

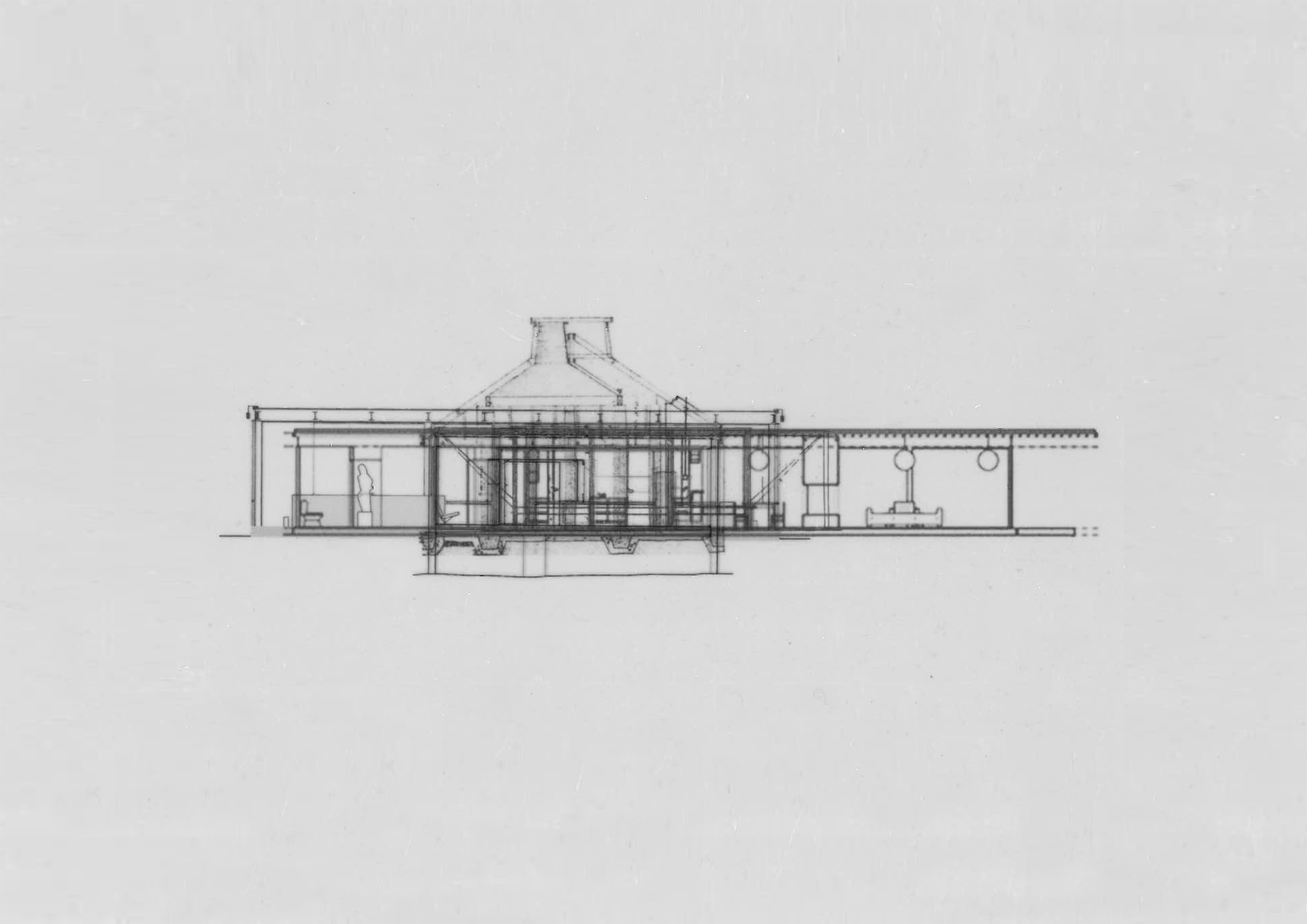

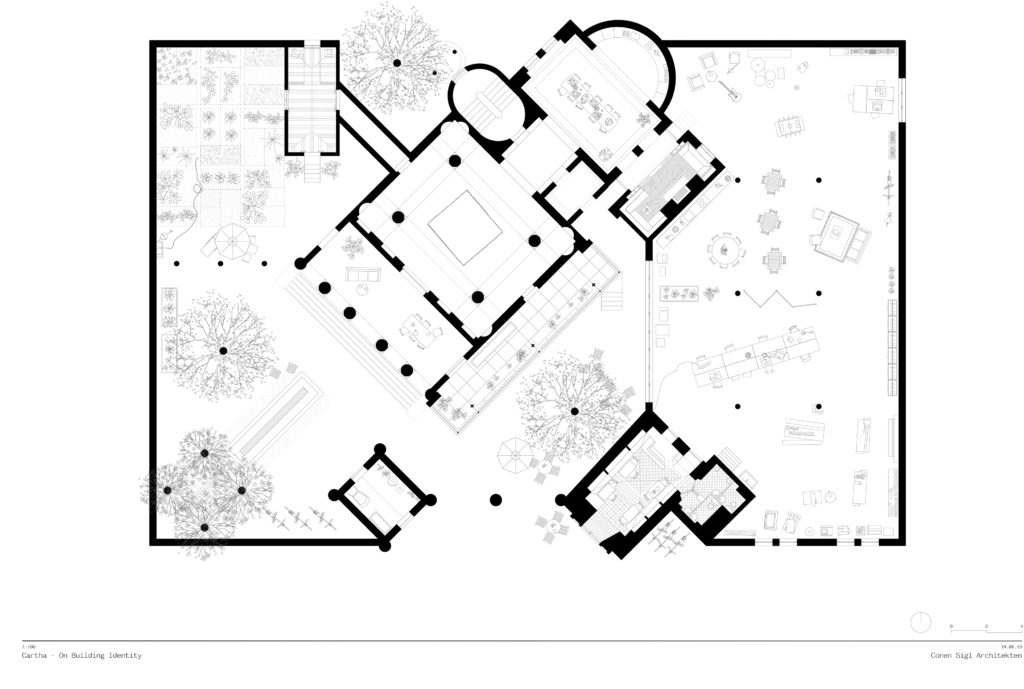

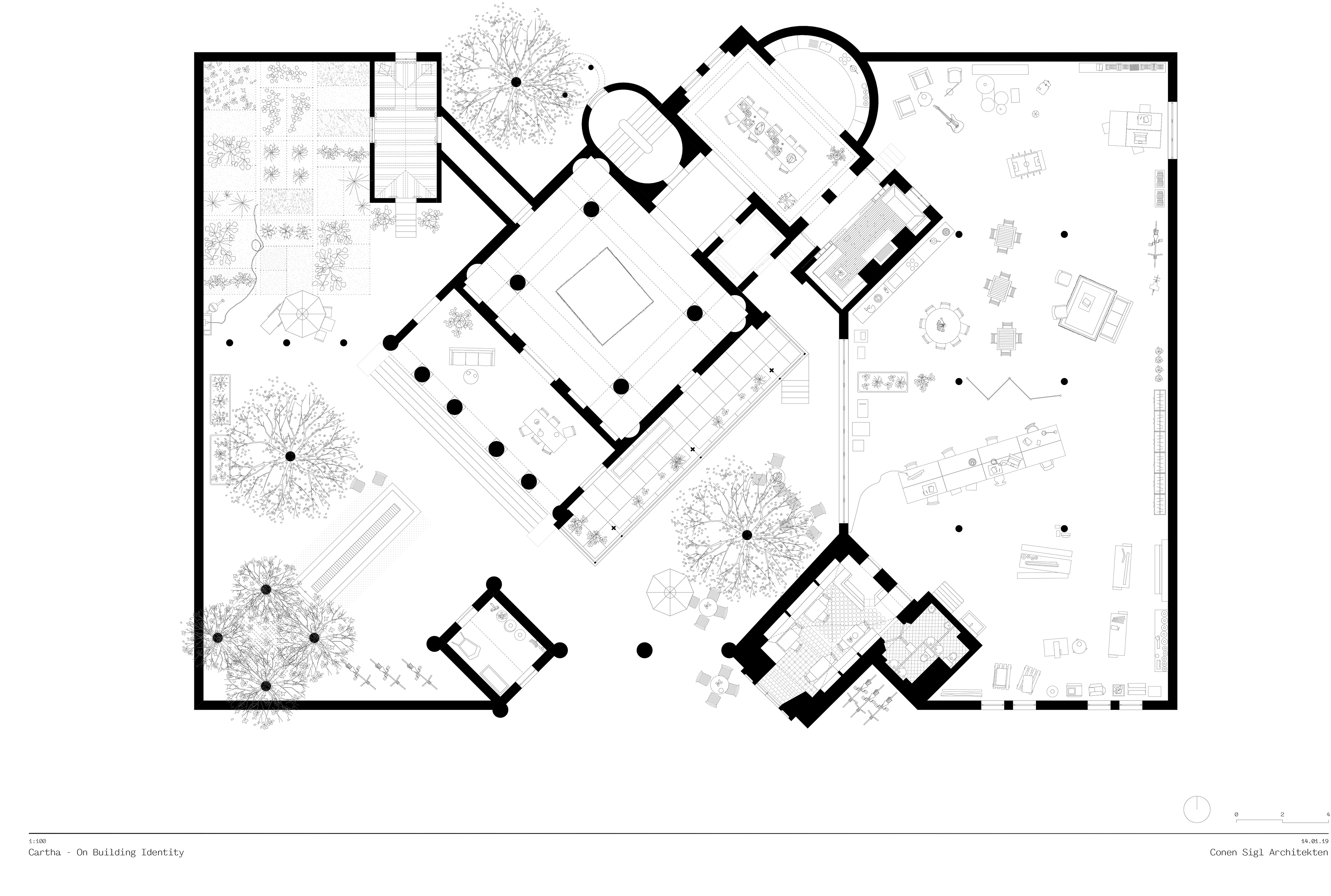

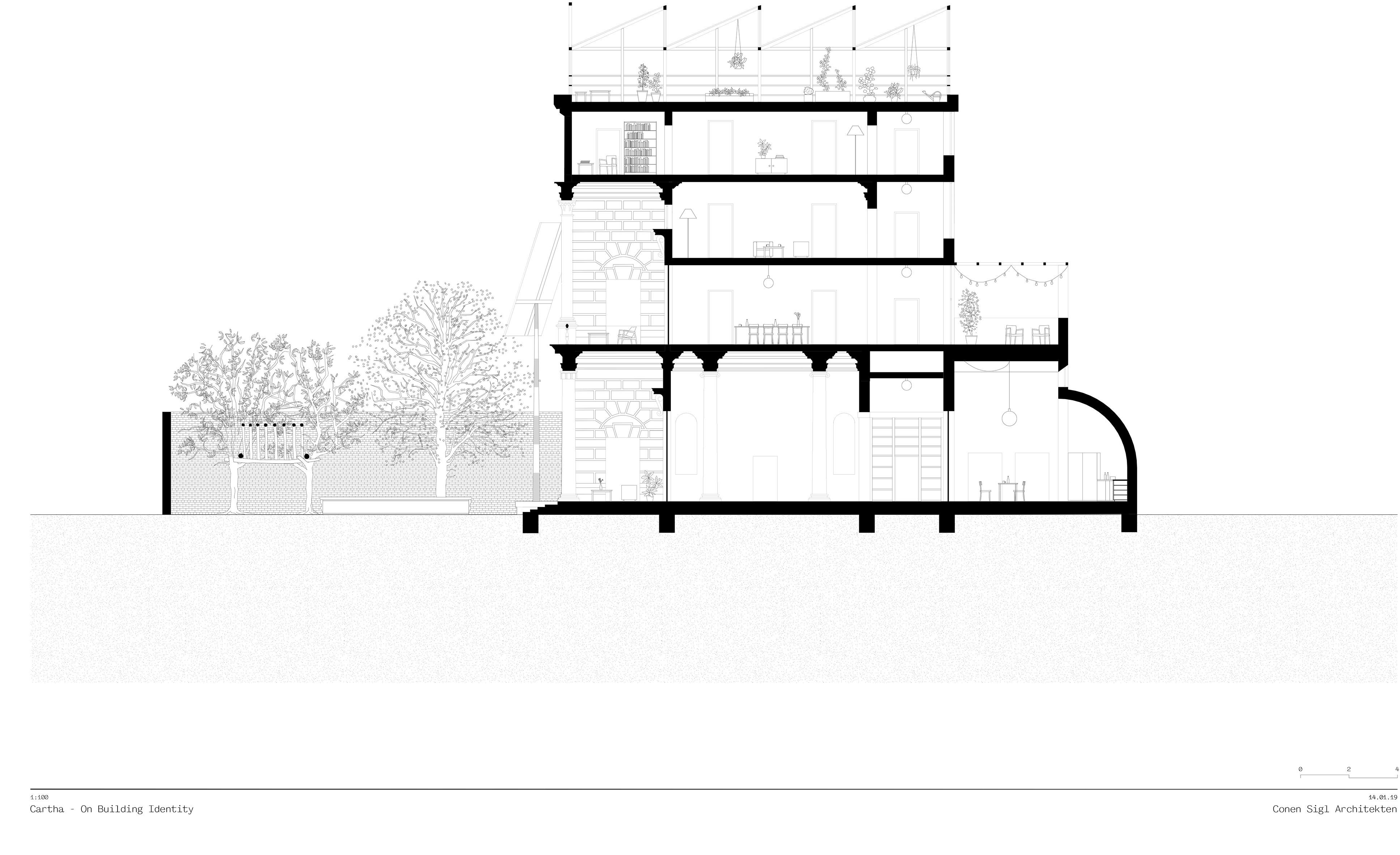

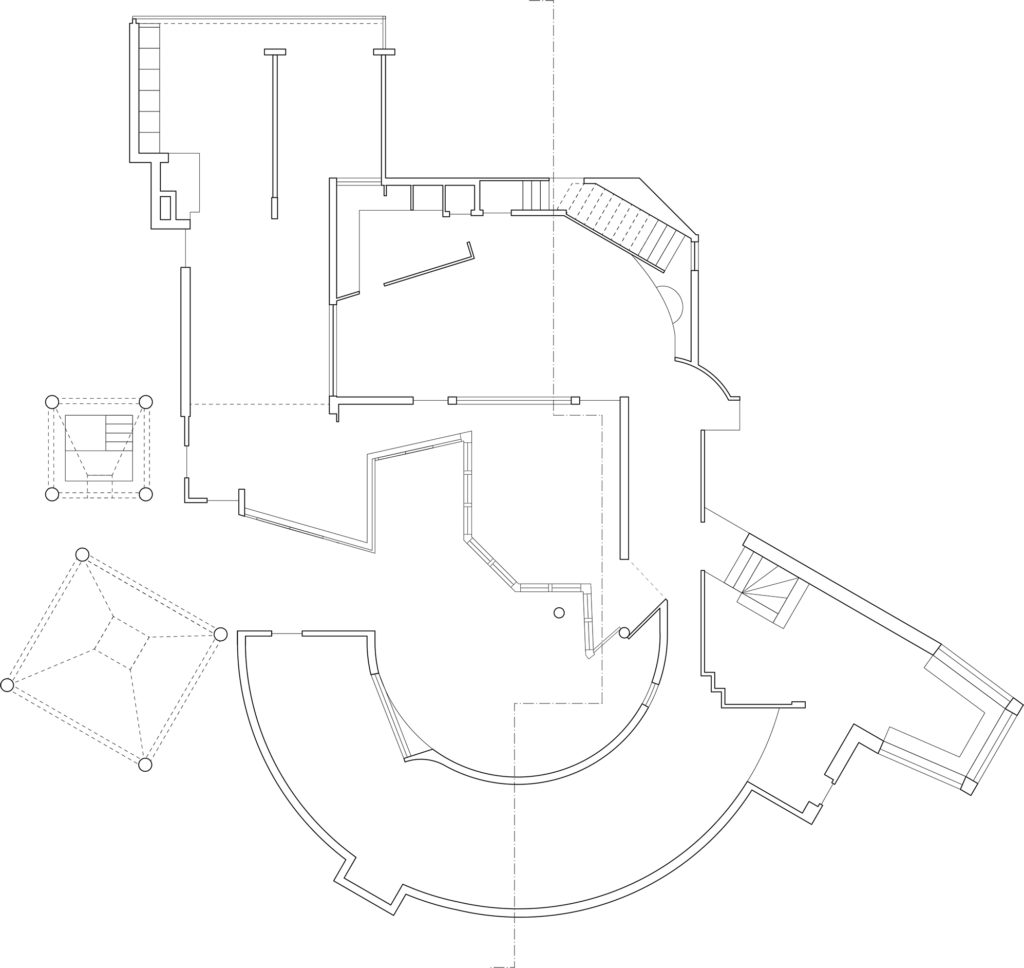

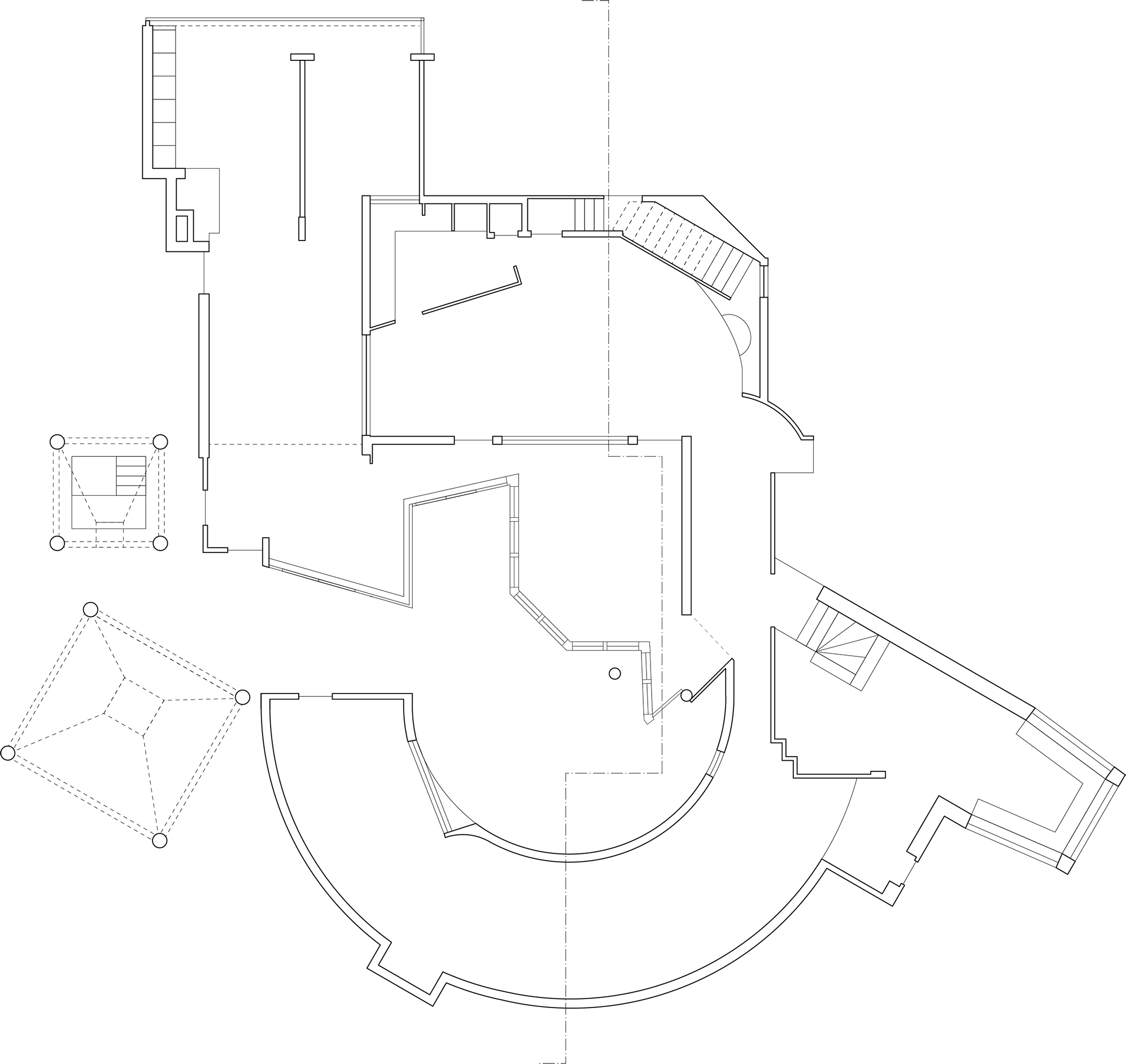

The practices Made In, Sam Jacob, Monadnock, Bruther, Bureau Spectacular, Conen Sigl and Muoto have been invited to take on a projectual task similar to the one Collens undertook. The aforementioned identity building processes acted as guidelines for the design process, challenging the architects to design a new dwelling (house, apartment, manor, hut, etc), drawing from projects inserted in their own conceptual, social, and physical contexts but not designed by them.

Alongside the projects, a commentary by Kenneth Frampton on the relation between identity and architecture widens the scope, questioning which role could architecture play in the current global political situation, and proposing a new lenses through which one can look back at the whole cycle.

The departing questions for this cycle are not only addressed but also answered in this last issue. The results of the speculative design exercise, beyond featuring a richness of references and depth of understanding of the meaning of previously built projects, promote a reflection on the contexts and situations the invited architects face. Interests in the current notions of social interaction, ideas of property, drastic shifts in environmental conditions and conceptions of history and future are brought forth in critical, seductive ways. The virtuosity displayed in the projects thus allows us to answer the question of authorship, for the creation of new meanings is indeed the emergence of a new identity, therefore of an independent person, a self. Furthermore, when facing the projects featured in this issue, alongside the visual and text essays published throughout the cycle, identity does seem to be able to promote a positive complexity in architecture, even when addressing the most common, most essential of typologies.

Nevertheless, it is not our intention to present an approach to architecture through identity as a definitive path, rather to propose it as an enriching complementary analysis and project methodology. The notion of identity, as proposed by this cycle, forces one to adopt a critical position towards a context. It promotes a deep understanding of what the now is by asking why it is so, what has been rejected if this has been appropriated, what has been lost in the constant processes of assimilation, and what the outcome of a more conciliatory approach might be.