Introduction

Initially emerging in Northern Italy, the Renaissance displayed an elegance and an impetus for progressiveness that European powers were eager to seize for themselves. An example for this desire can be found in Juan Bautista Villalpando, who referenced the ancient motifs as an expression of imperial power for the Habsburg Empire. This usage, however, uncoupled the new architecture from its regional context: without this relation to a regional imprint, the use of the ancient motifs entered into a self-referential context. As a result, Renaissance architecture could be appropriated to convey imperial power as well as to perpetuate the Dutch Republican identity. For example, in the Dutch Republic, growing in power after the rebellion against the Catholic King Philip II, it seemed to be more appropriate to display personal success in a civil society than to subjugate oneself by paying for construction projects as representations for the splendour of the King or pompous sacral buildings. This aspiration raised the demand for a method that would generate buildings that are equal in kind and yet differentiated in form and ornament to signify the social status of any single member of society.

To exemplify this, Nicolaus Goldmann and the method he devised will be chosen as a role-model for architectural appropriation. Goldmann, originally a legal scholar and mathematician, was born in today’s Wrocław. But he was given the opportunity to move from Silesia, severely affected by the turmoil of the Thirty Years War, to the University of Leiden, which had recently been founded under the motto “Praesidium Libertatis” and accepted scholars regardless of nationality or denomination. In Leiden, Goldmann devoted himself to studying architecture, and although he is almost forgotten nowadays, his work Vollständige Anweisung zu der Civil-Baukunst (Complete Manual for the Civil Art of Building) is particularly interesting as a methodology for appropriation for several reasons.

The Self-Referential Model

One of these reasons may be that Goldmann, although he undertook several journeys, stayed at the University of Leiden from his beginnings as a student in 1632 until his death in 1665. This fact supports the assumption that he continued updating his Complete Manual as the basis of his teaching and as a mirror of the prevailing zeitgeist until it was published posthumously.

Another reason may be that the Complete Manual presents itself with an extremely rigid and disciplined structure, which makes it most likely that Goldmann had been influenced by a man who was enrolled in Leiden from 1630 on to study mathematics. This man, who anonymously published a book seven years later while he was still in Leiden, was René Descartes, and the book was entitled “Discours de la Methode”. One indication that Goldmann indeed was influenced by Descartes appears in Goldmann’s explicit claim to teach architecture “in a scientific way,” developing what he called a “synthetic approach.”

But of course he did not start synthesizing on a blank sheet. He instead neutralized the contextual elements of Renaissance architecture, such as regio (the region), area (the plot), partitio (the partition), paries (the walls), tectum (the slab), and apertio (the openings), which often reference local conventions, by abstracting them for a self-referential methodology. The architectural elements are split up in a dualistic manner; their intrinsic properties enter into a fourfold method, abstracted from their particular contexts. Goldmann conceived from the outset that buildings were hypothetical and context-free.

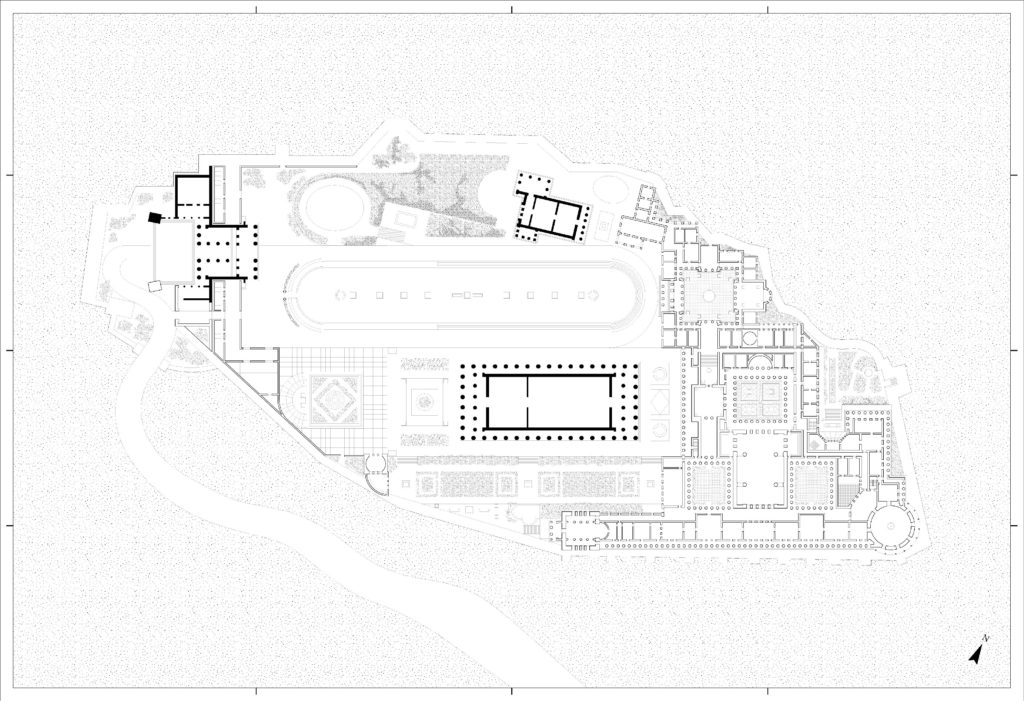

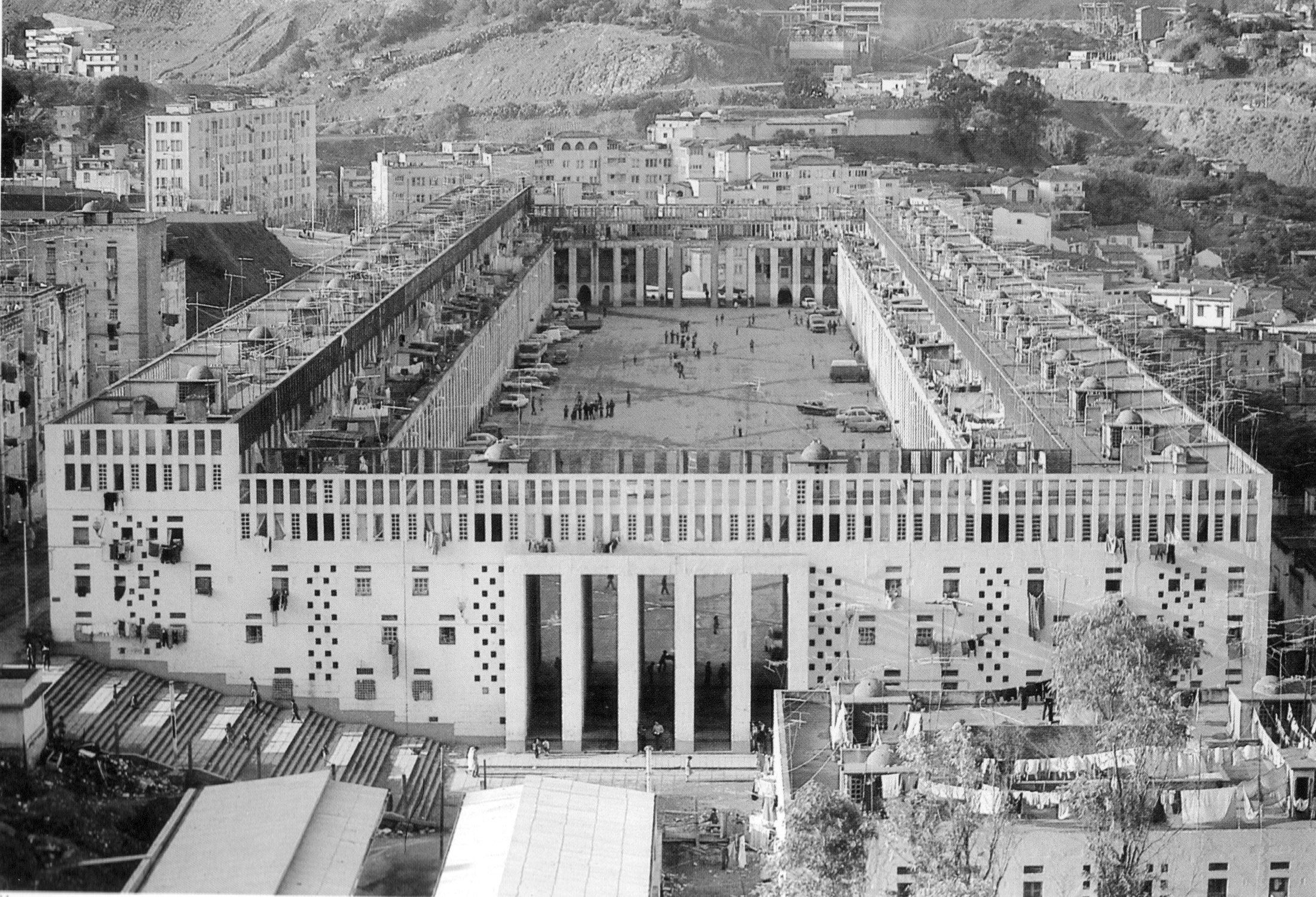

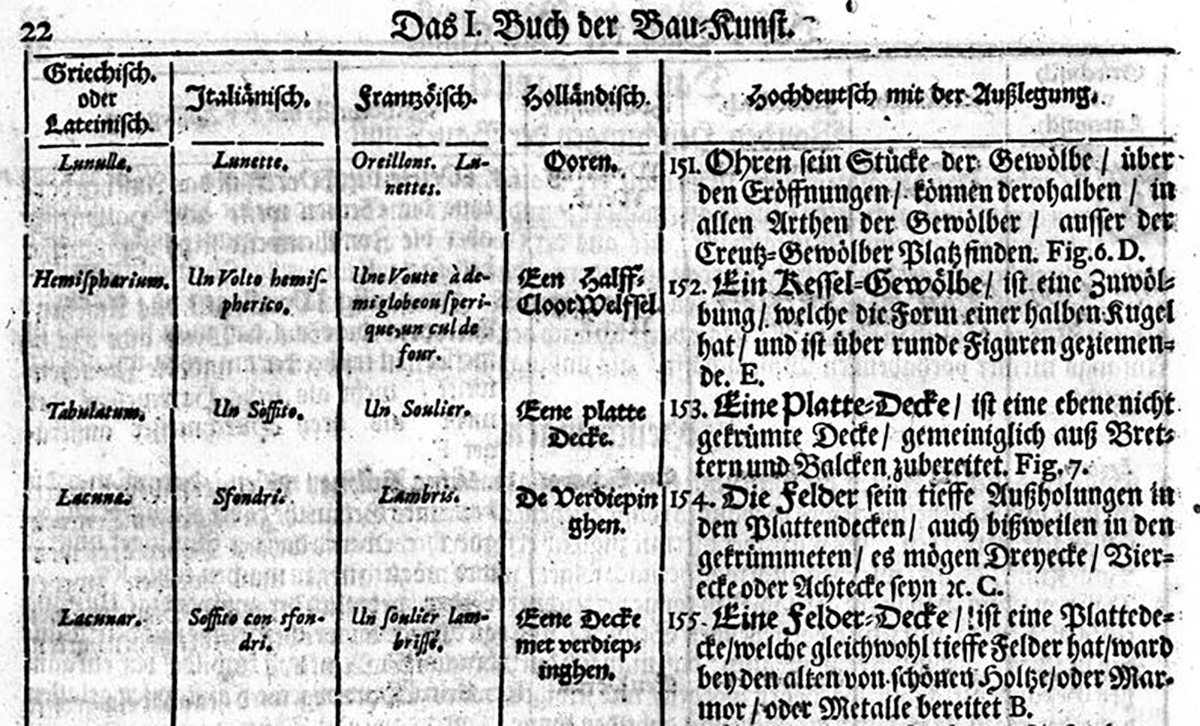

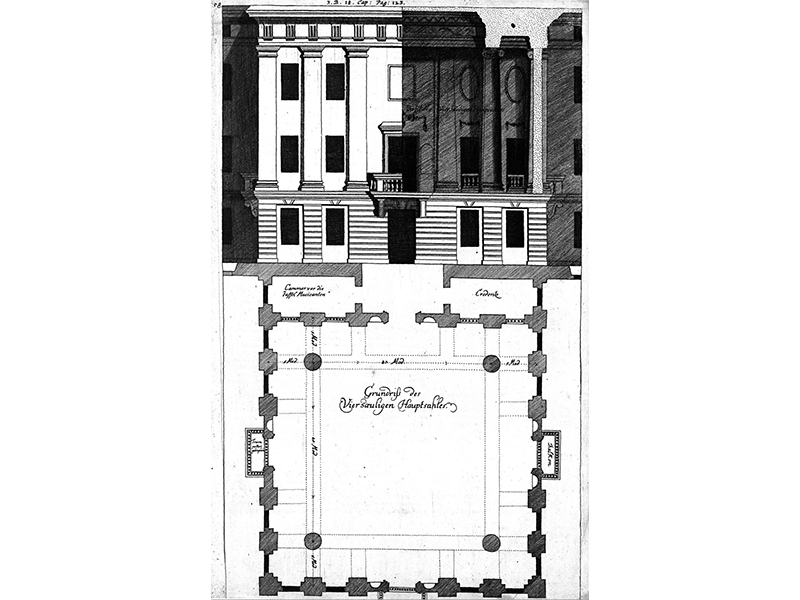

He begins his first book with the “Definitiones,” which he considers to be an exhaustive list of components. These components bear the extrinsic attributes of elements: the motifs that can be described through geometry. To achieve stability in the definitions, Goldmann was identifying for each one the equivalent terms in Latin, Italian, French, and Dutch together with a short description [Figure 1]. Second, he begins to formulate postulates, stating that the mathematical sciences reach out to each other in such a way that the tenets on which they are based can be considered as true and established. His first and most important postulate is that it is possible to utilize the “art of measurement” to draw plans with sufficient precision to build from. In the third place are his “Axiomata,” in which he summarizes the rules of building technology. Finally, in the fourth part, Goldmann lists and describes thirty-three different “whole works:” churches, schools, hospitals, etc., categorized by utilization: sacral-secular; private-public; “for coming together, for contingency, for splendor.”1

Figure 1 Excerpt from Goldmann’s “Definitiones“

Only after these idealized types have been defined, does he describe how to adapt them to a particular situation in as many steps as necessary for the specific building. He also pointed out that this method has to be understood as a self-contained order, relying on the reader`s willingness to accept its contingencies and consistency and not to tamper his definitions with different interpretation.

Appropriation: Specification, Signification

However, the residential building was the only type for which Goldmann goes through the motions of design. In the first step, neither the location of this building nor its appearance are considered. In this respect one, can speak of an ideal that exists detached from any context. Before a plan is drawn, before the actual design is taken into account, Goldmann determines exactly where each room is to be located in the layout of the building as a whole according to functional requirements. In order to further substantiate this general type, he suggests that regional aspects might influence the specification of the building and thus allow for the formation of variants.

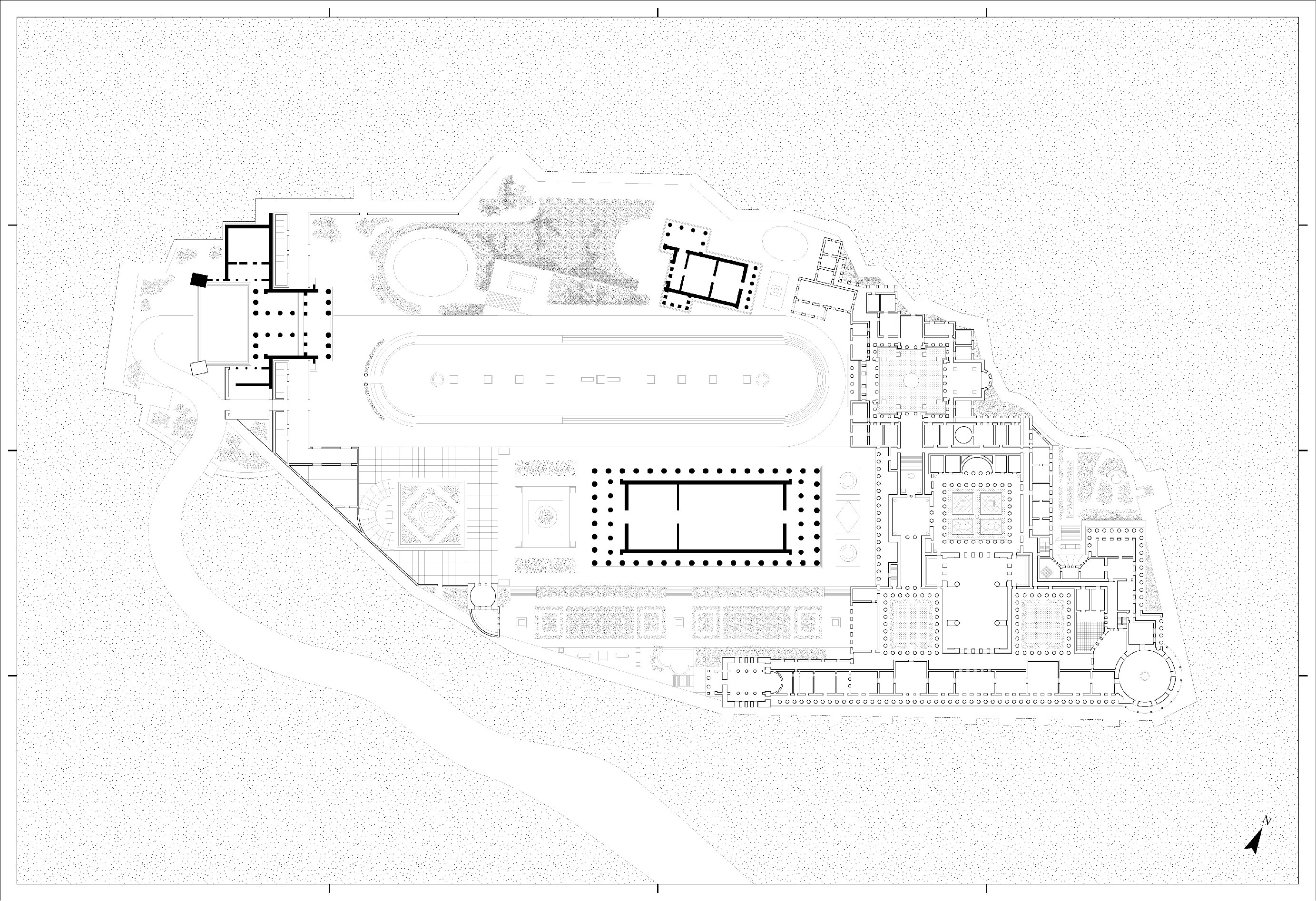

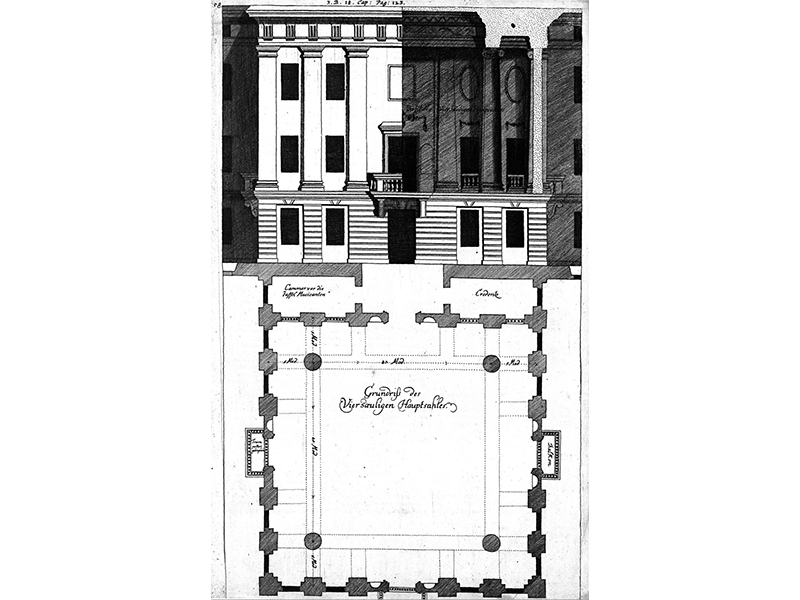

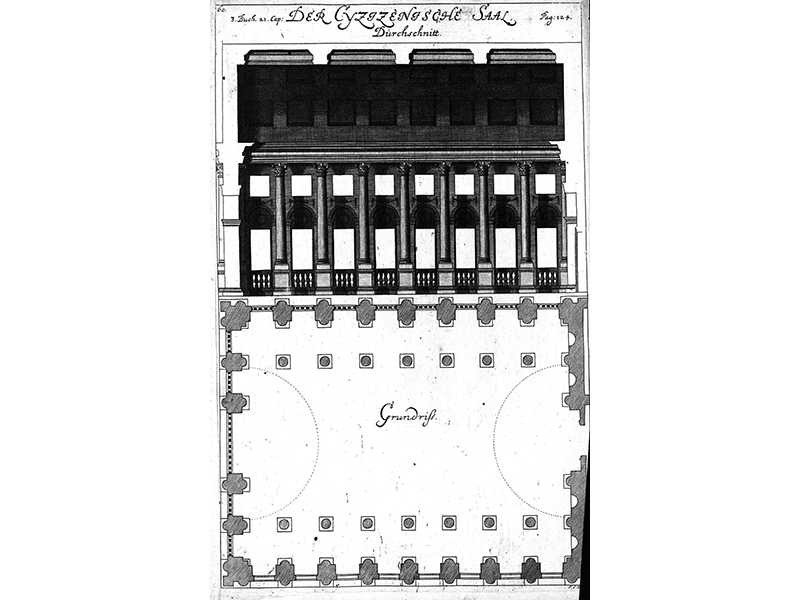

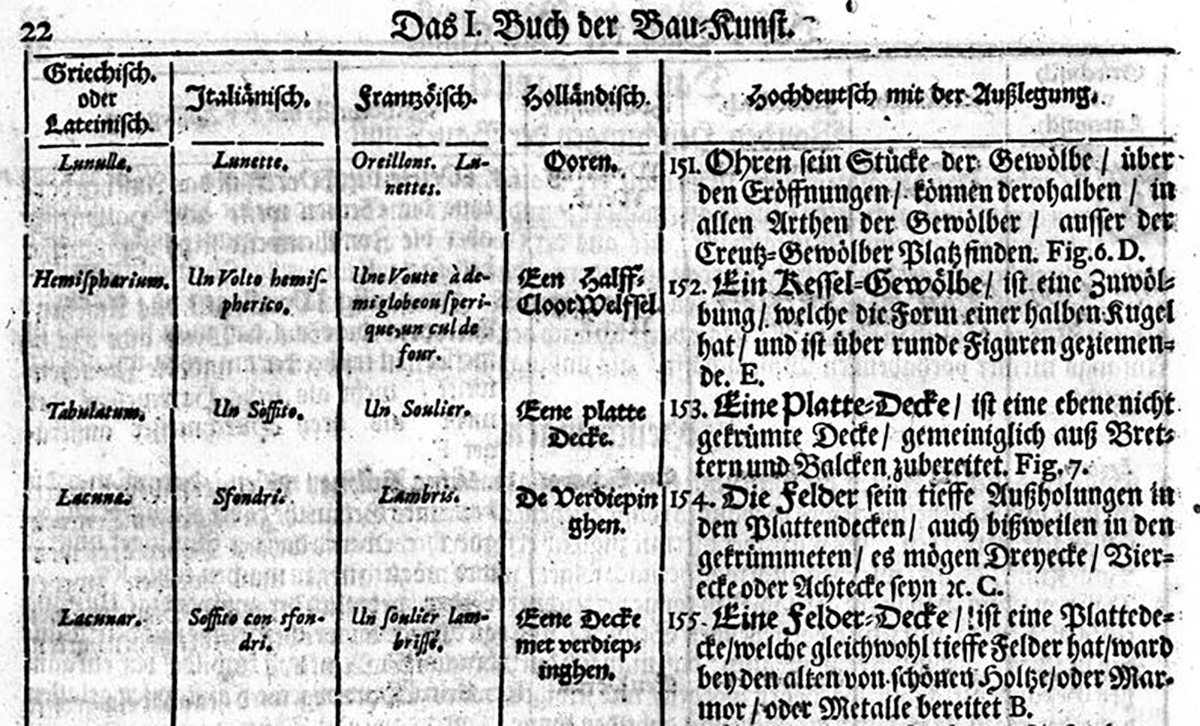

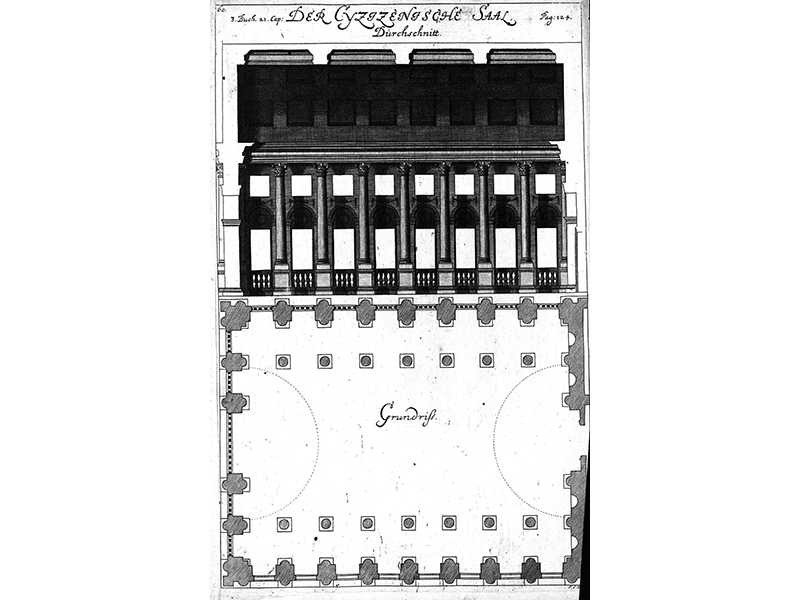

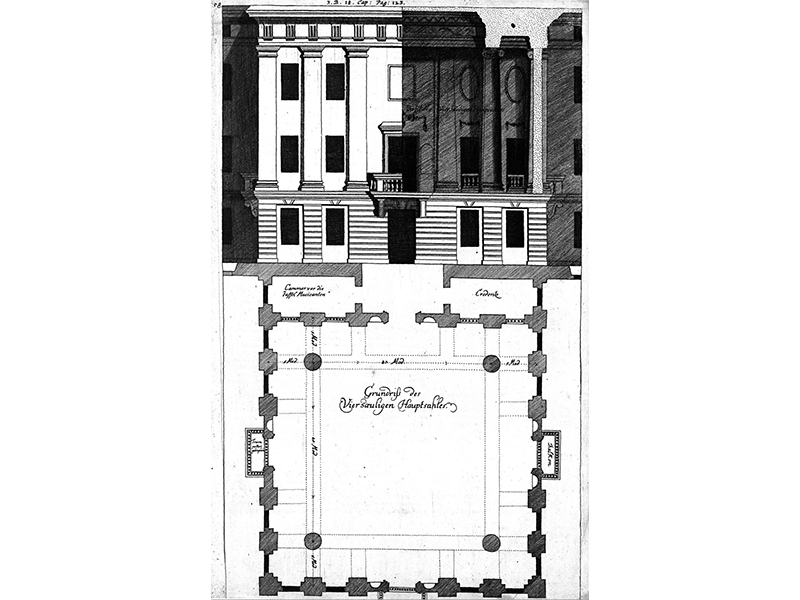

The first step in the appropriation for a specific identity happens at this moment in the design process by indicating that arcades in Italy, foyers in France, or heated parlors in Germany would correspond to regional habits. Goldmann treats individual rooms similarly, but here it is less a question of regional or local imprint. He lists several types for the “main hall,” that are mutually equivalent to each other and remain interchangeable by taste or fashion [Figures 2a & 2b].

Figure 2a The “Asian Main Hall” as described be Goldmann and il- lustrated by L.C. Sturm (ed.).

Figure 2b The “Main Hall with four Columns” as described be Goldmann and illustrated by L.C. Sturm (ed.).

He also suggests that the interior paintings should reflect the identity of the client. He proposes to indicate the social status of high lords with depictions of epic adventures, while landscape paintings would be more suitable for common people. For the ornamentation of a building, he argues that skulls of oxen could be placed over the frieze of a meat market as an emblematic signification for the purpose of the building. Thereby, the building becomes increasingly qualified, while the option of creating variants is kept open for as long as possible. With the Dutch Republican identity in mind, Goldmann refuses ornamentation for the sake of decorating. Unlike his predecessors, he keeps a critical distance towards ancient architecture, critiquing the ostentation of his own epoch. Goldmann demands ornament to function as a kind of appropriation by signification that not only serves to individualize the building but also to identify the purpose or person it was built for.

The Interface

There is one last point to bring up, which may be the most indirect and yet most relevant for the methodology. It is introduced by Goldmann as the “main sketch”:

“Lastly, it is not to be denied that the builders do not speak a word about the main sketch / because they have considered it to be a part of the floorplan: but this separation of the names and inventions will be thankfully accepted / by all those who prefer good instruction and easy inventions.”2

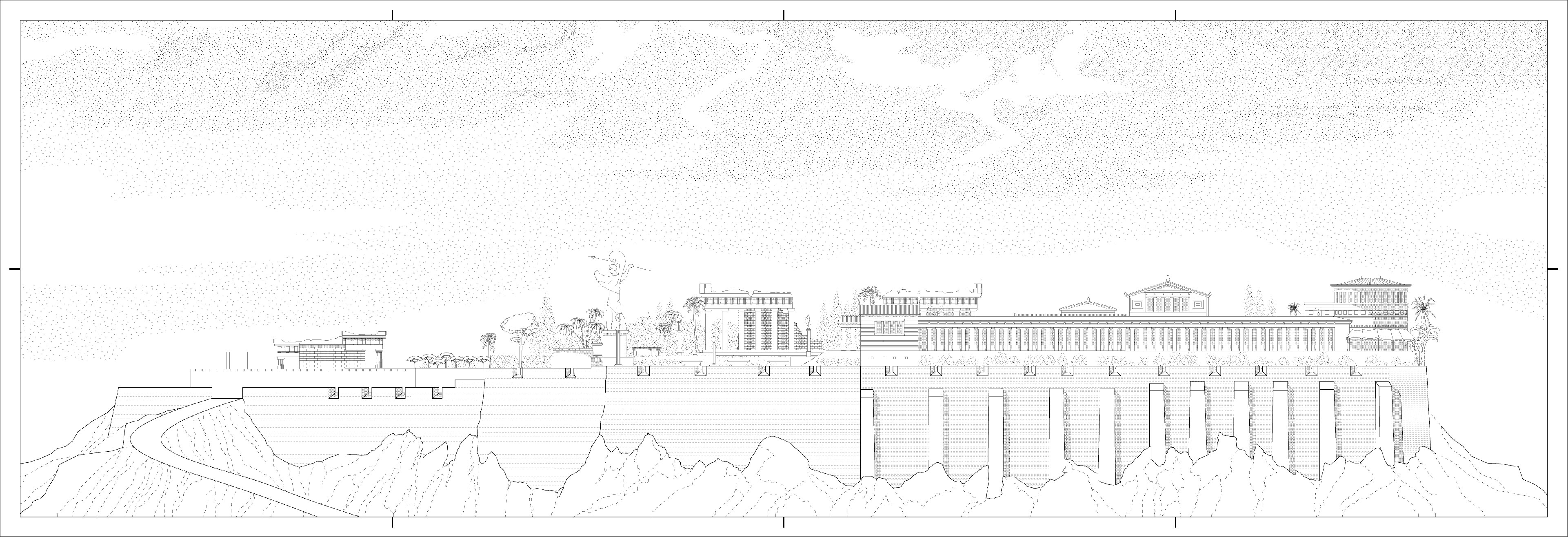

Namely, these “builders” are Vitruvius, Palladio, and Scamozzi, from whom he wants to differentiate his conception. He defines the “main sketch” as a plan so simple that the depicted objects appear only as a footprint. Thereby, it acts like a boundary between levels of scale, working like a symbol to encapsulate whatever it should represent. A house to the city or rooms to the house appear as black-boxes only defined in terms of their type.The main sketch draws a reference to another set of plans spelling out what it actually shows and where the process of variation or specification is kept open. Every part of the building behaves like a variable in a mathematical equation, embedded in a formal set of rules. This “boundary” functions at each scale as an interface between entities of planning.

Goldmann exemplifies this design process not only by means of an exemplary house, but through multiple the levels of scale; starting with a detailed instruction of how to execute a Corinthian capital and ending with his ideas for an ideal city. In the sense of a context-free pre-specification, there is no uniform principle or grammar, but instead, a formal method to treat the entities of planning as variables, capable of including objects of the same category but of different characteristics, like the various “main halls”. These variables are identified with each other and therefore conceived as interchangeable, without affecting the overall layout of a building. At the same time, every encapsulated entity can have its own set of rules and expose the same internal capacity for sophistication.

One to Many and Many to One

In Goldmann’s abstract model, this same method could be appropriated for many identities. Or, as Descartes might have put it: the identification of interchangeable entities made it possible to relate equivalent terms to one another3. The abstract idealization of a building with no form or appearance can successively undergo several steps of appropriation to take on the required identity: asa regional adaptation, signification of usage, or reflection of the taste and status of a client. The advantage being offered by the underlying model is that it provides a robust architecture for the specification and differentiation of the final design. Goldman, adapting Mediterranean motifs of antiquity to the particularities of the Dutch built environment, created a model for constructing European identity, devising a method of architectural abstraction and appropriation.

1Goldmann (1699), p. 128

2Goldmann (1699), p. 51

3For example. Descartes, 1925, p. 16: René Descartes states that by providing four different ways to extract a root, he can cover solutions to all possible equations containing a root. And by this, a root is not an obstacle anymore that requires to be worked out particularly, but in can be replaced, or identified, with an equivalent term.

Dennis Lagemann is a Doctoral Candidate in Architecture. He holds a Diploma of Engineering in Architecture and a Master’s degree of Science in Architecture. He conducted additional studies in Philosophy and Mathematics at the Department of Arts & Design in Wuppertal and at ETH Zurich. He was teaching CAD- and FEM-systems, worked as a teaching assistant in Urban Design and Constructive Design until 2013. On the practical side, he worked for Bernd Kniess Architekten on multiple housing and exhibition projects in Cologne, Dusseldorf and Berlin. In his research activities, Dennis was a member of PEM-Research-Group at the Chair of Structural Design at the University of Wuppertal, where he became a Doctoral Candidate in Computational Design. From 2015 on he is participating in the sci- entific discourse about computation in Architecture and giving talks at conferen- ces, including ACADIA, CAADRIA and ArchTheo. He is now located in Zurich at ETH / ITA / CAAD. His main research interest lies on the question how histo- rical and contemporary notions of space, time and information are being addressed in Architecture.