BRUTHER

Stéphanie Bru and Alexandre Theriot emailing with Francisco Moura Veiga

Dear Stéphanie, dear Alexandre, I trust you are doing well and that spring has been kind to you. It was back in 2018 that we first reached out to Bruther with a playful challenge: you would have to design a house using only parts and pieces of other projects, by other architects. This was the […]

Dear Stéphanie, dear Alexandre,

I trust you are doing well and that spring has been kind to you.

It was back in 2018 that we first reached out to Bruther with a playful challenge: you would have to design a house using only parts and pieces of other projects, by other architects. This was the brief proposed to a short number of offices and the result would make up the 5th issue of Cartha’s 2018 editorial cycle: Cartha on Building Identity.

Faith had it that tomorrow I will be presenting the book that resulted from this editorial cycle. (By the way, how did you find the book?) I have obviously been going over your contribution and those of the other offices, and a couple of questions arise:

- Why did you accept doing the exercise in the first place?

- What motivated your choices of references? Or, in other words, fully owning the exercise’s brief and its Lacanian roots, why did you choose to project your identity through such a building? You speak of “architectural appetites” in your text but what are the reasons behind these appetites?

- And why that long, enticing title?

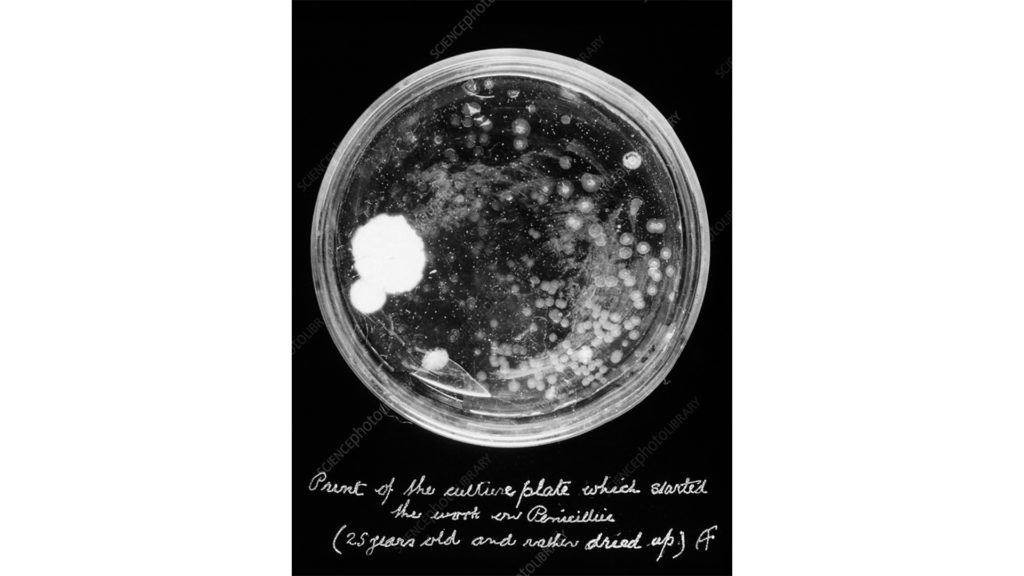

Your project always took me to a place of chaotic possibility: a petri dish. More specifically, Alexandre Fleming’s penincillin culture rephotographed in 1928. The visual cues are quite obvious but that is not the point. The connection I see lies in the specificity of the interstitial spaces and in the definition of the borders as the “magic circle” into which a non-predictable life can expand, with the built structures acting as trigger points rather than limiting mechanisms.

Fleming’s petri dish culture reshot after 25 years.

Whatever happens inside raises questions, does not offer closed answers. May that be the reason behind the title?

Looking forward to your reply!

All the best,

Francisco

…

Dear Francisco,

Thank you for your message — it moved us in many ways: your attentive reading, the poetry of your words, and this thoughtful reactivation of a project which, despite its initial playfulness, became for us a space of very serious reflection. The book is still at ETH, unfortunately — we haven’t seen it yet, but we’re looking forward to it.

You asked why we accepted the challenge a few years ago. Probably because the exercise, behind its light tone, offered a rare opportunity: a speculative space where our “architectural appetites” could unfold freely, with no imposed program or context, but in dialogue with the history of architecture. A space of critical, almost theoretical, freedom, where we could make our obsessions, our references, our favourite fragments coexist — not in search of coherence at all costs, but of intensity.

Why those particular references? Perhaps because they reflect our internal tensions: between the ultra-precision of detail and the intoxication of utopian plans; between the desire for assemblage and the pleasure of raw juxtaposition; between the machinic breath of the Maison de Verre or the Chemosphere, and the vernacular alveoli of the Mousgoum village. What you describe as “appetites” are those deep, sometimes contradictory, attractions that drive us — a taste for visible mechanics, for breathing systems, for forms that engage the whole body, both at the scale of gesture and of territory.

As for the long title — How are you / Hello, how are you? How did you sleep last night? Did you dream of me all nights?— it acts for us like a threshold. It opens a space of fictive, almost psychoanalytical intimacy, where architecture becomes language, address, riddle. It is a question posed to the visitor, but also to ourselves — to our projective desires. Architecture is less an object here than a link, a relational potential.

Your analogy with the Petri dish really resonated with us. Yes, there is undoubtedly this sense of fertile experimentation, where the interstices matter more than the objects themselves. These voids — magnetic fields, we might say — are what organize the possible. And what you call the “magic circle” indeed echoes this idea of an unbounded space, an undefined enclosure open to all contaminations. A stage more than a setting, a device more than a plan.

And now, two questions for you:

- Looking back, has your reading of the projects changed? Do some references or gestures speak to you differently today?

- You mention interstices and ambiguity — does that resonate with the way you edit Cartha?

Could Cartha itself, in some way, be a kind of Petri dish?

Best

Stéphanie & Alexandre

…

Dear Stéphanie, dear Alexandre,

Your beautiful explanation was more than just that: it did not simply settle doubts, it brought yet another intensity to your project. This process of enthusiastic, critical review that you took me along with you is precisely the same process, and I think I can speak for the rest of the current Cartha team, we want to propose for this last year of editing: to revisit What Remains.

This is in itself an answer to your question as it definitely prompts a renewed reading of the “Building Identity” projects and of every other article, image, or project we have published in these last 10 years. Your suggestion of Cartha as a petri dish, that had obviously eluded me despite being in front of my eyes, is, I believe, the biggest compliment and the highest expectation we could have for this editorial experiment we undertook.

Going back to your question on the evolution of the reading of knowledge, there could be many models of understanding for this constant updating of ones relation to “known knowledge” but there is one that, though probably not being the most accurate, greatly resonates with me: Lev Vygotsky‘s take on learning. In a nutshell, he states that learning is necessarily contextual (you will be coming across a text of his in the Diploma reader the Voluptas chair is currently preparing). As your context changes–and you with it–so do the connection points between knowledge and yourself.

This brings me to the concept of desire you brought up, or “projective desires”, as you beautifully put it. According to Deleuze and Guattari, desire is itself necessarily contextual. The house you desire today is not only “the” house itself but the whole physical, conceptual and social contexts it is inserted in.

And there is yet another layer for our choices–the ways in which we act upon our desires–as citizens and as architects, are not only contextual but have in turn an influence on our contexts, as you have been eloquently stating through your work since your very first won competition for the Pelleport housing project.

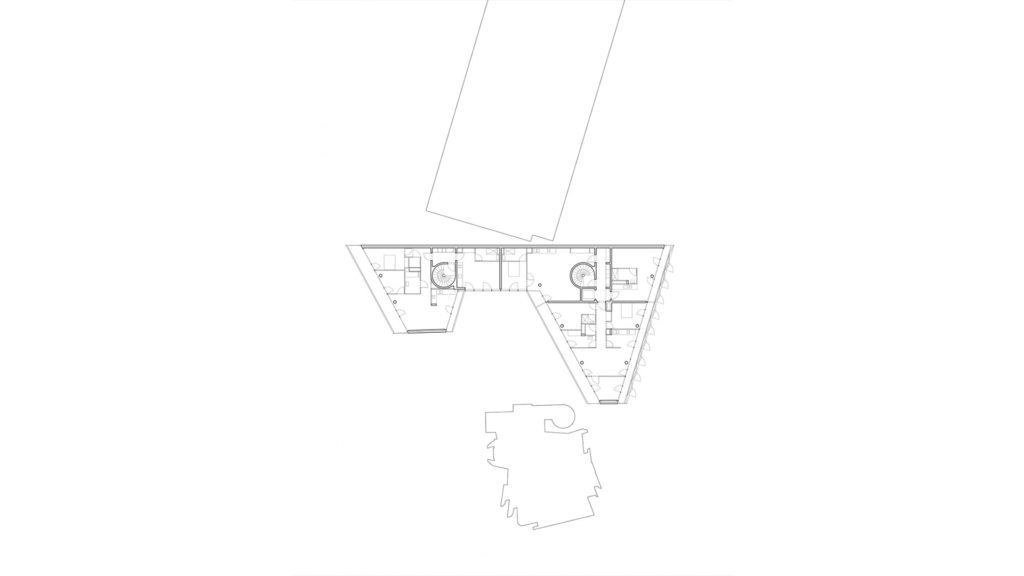

Pelleport Housing Project, 13, rue des Pavillons, 133, 135, rue Pelleport, Paris, France completed in 2016.

So the inescapable question is: how do you situate your desires in your own context?

I will not ask you how your house for the Building Identity exercise would be in lieu of your current context but I want to ask how your projective desires have evolved in the last 5 years? Or, maybe, to make it easier and more precise, how would a construction system you would design nowadays be influenced by the shifting weights of material and energetic economies at a global and local scales, and of societal values regarding comfort and ecology? A 1:5 detail of a Musgum house is on the other end of the spectrum of a Maison de Verre…

Can’t wait to read your thoughts on this!

Wishing you all the best,

Francisco

…

Dear Francisco,

You invite us to situate our desires within our own context. We understand this invitation as a test: to accept that time, references, and environments constantly reshape the way we speak, build, and inhabit projects. Images circulate, smooth out, resemble one another; the social climate demands visible virtues; material and energy economies impose measured frugality. In this framework, our desires do not settle on a form-object as an end, but on the capacity of a device to host heterogeneous forms of life and to reconfigure itself. Between a Maison de Verre and a Mousgoum house, we do not read an exotic gap, but a continuity of questions: how to ventilate, assemble, economize, share, repair? Where to place intensity? Where to leave voids?

We have learned to shift from one “performance” to another, to accept that a project is only a transitory state in an unfinished chain. To act, to welcome accident, to remain adaptable: this is our way forward. Each intervention assumes that someone, later, will take up the thread with other tools, other urgencies. We therefore conceive open systems, where one can subtract, add, cut out — and what do we take off now? — so that the rightness of the moment takes precedence over the closure of the object.

In recent years, our desires have shifted: fewer isolated objects, more operative environments. We work on adapting inherited typologies as much as on emerging ones, in a society where the nuclear family is no longer the axiom. Domestic life is mutating: assistance robots, distributed care, friendships as infrastructure, end-of-life planning, intensified work despite automation, simultaneous dependencies, the cult of sharing and growing solitude. We did not wait for 2020 to understand this, but the pandemic revealed the fragility of the all-mobile and taught us to convert mobility into malleability: Swiss-knife dwellings capable of absorbing work, learning, care, retreat or celebration without redrawing the plan at each crisis.

Rather than stacking functions, we cultivate appropriable pockets: interstices, spare rooms, useful thicknesses, where the unforeseen finds its stage. These bubbles of lightness contradict the hyperspecialization that generates its own bugs. They create atmosphere — not décor, but conditions: light, air, continuities, thresholds. The comfort we seek is not normative redundancy, but the possibility to reconfigure without violence.

We like to imagine the building as a hospitable machine: not a closed shell, but a body equipped with autonomous organs — ducts, antennas, pipes, walkways — where breaks become joints. Inside, everything remains fluid; the whole recreates a small world, reconciles divergent uses, and leaves choice. A prosthesis of the everyday, it adapts and assumes not to “know exactly what it is” in order to learn better from those who inhabit it.

Lightness is not an effect, it is a critical structure. Putting the heavy above and the light below, exhibiting the construction site rather than erasing it, accepting that a glass envelope reveals the strata: structure, partitioning, skin, curtains. This dematerialization does not erase matter; it expands it through the intelligence of joints, that mirror which dilates the tiny room, that clear reading of the skeleton that makes beauty almost anatomical. Constructive truth becomes a resource of space, emotion, and use.

We advocate for elemental energies, carefully controlled. Compressed air, for example — a poor and precise energy — is able to lift tons of fresh concrete and shape natural geometries. Properly mastered, minimal pressure produces frugal forms, merged with the site, far from over-technology. Similarly, cross-ventilation, inertia, shade, or gravity-fed water become powerful low-tech if architecture gives them room.

To be alchemists is to hold together analytics and sensitivity. The right measure — neither dogma nor opportunism — is obtained through shifting balances between local resources and global networks, between reuse and industrial precision, between rules and exceptions. This reconciliation of opposites is not compromise, but a method to keep action just, here and now.

Everything begins with a question. We are not looking for the answer, but for the formulation that opens a passage. To walk along the ridge, to accept that the discipline stretches to its limits, is to assume confrontation with uncertainty. Value is not in the hierarchy of media, but in the intensity of gaze and the clarity of trials. It’s too late to be late (Bowie): better to fail fast and adjust than to perfect too late.

The present is fleeting, globalized, connected, contradictory. Rather than enclosing it in a narrative, we arrange margins of rescue — cloud catchers that capture uncertainty and redistribute it as possibilities. Let us give value to spare spaces, turn constraints into resources, transform the indeterminate into useful plasticity.

For us, there is a formative memory: the aligned pavilions next to the fields, the incomplete city where life disperses in juxtaposed fragments. It is there that emerged the desire for a simple and open architecture, not for the image but for generous indeterminism. To be a citizen is no longer to remain a spectator, but to step fully into the world, fabricating social condensers rather than totems.

We treat budget and time as project materials. Economy is not reduction, but selection. Cedric Price taught us: better an evolving system than a closed form. Bernard Stiegler reminds us that the tool transforms our ways of living: let us design devices that educate desire rather than exhaust it.

Concretely, we design readable and modular structures, capable of bifurcation without heavy works; active exterior circulations as places of exchange and microclimates; compact technical cores that free up large undifferentiated floors; low-tech façades privileging manual maintenance and appropriation; and plans that reserve waiting zones where work, care, play, retreat can settle. And we deliberately remove programmatic overload, useless automation, dependence on centralized control. Less domotics, more sockets and brackets; less image, more act.

Our desires shift, then, from the ideal form to the potential of transformation. We situate our work within this mobile rightness: a sober alchemy, a hospitable machine, a malleable environment. We are not looking for an answer; we are looking for a way to formulate it. With each project, we try to catch a piece of cloud, long enough to refresh the climate of inhabiting, without ever pretending to fix it.

With all our friendship,

Stéphanie & Alexandre

…

Dear Stéphanie, dear Alexandre,

It might be clear by now that the core topic I wished to address in our exchange was that of the project: the project as a vessel, aligned with Bernard Cache‘s take, and the project as an event, along the lines of Derrida’s proposal.

Your last email tackled the vessel aspect in a most complete way: I can now understand how your projects are loaded and with what you load them with.

Still, I do see your work as a disruptive force of sorts. So, for my last email, I would now like to ask you to expand NOT on how your projects act as a system in their conjuring and function, but rather on how you see your work in its relations to society at large, to your fellow architects, and, highly important, to your students.

Your answer will be the conclusion of this exchange. I cannot thank you enough for the generosity and complexity of your answers. I truly hope you have found this an exercise worth doing.

All the best!

Francisco

…

Dear Francisco,

How do we, as architects, situate ourselves within the vast professional landscape, and within the even wider field of our socio-cultural environment?

There is a kind of vertigo in answering a question so broad, all the more since we prefer to remain modest – not to pretend to be the architect, the urbanist, the planner who would pronounce truths about the state of society and the world.

Our projects never offer a single answer. And our teaching even less so. One might think students arrive as blank pages, waiting for knowledge to be delivered from above. But we reject this verticality: we prefer to trust in their maturity, in their doubts, in their curiosities already in motion.

With them, we move forward like investigators. We search for the lines of force that weave through our time, social, ecological, economic… – and we learn together to push aside the obvious. Economy and excess have long formed the double rhythm of our reflections; two pulses that attract, contradict, balance, and shift again.

Above all, we invite them not to see architecture as a closed world. To perceive an engine as a neighborhood, a mechanical assembly as a fragment of the city. For to think architecture is to think of pieces that vibrate together, without fixed hierarchy, crossed by forces, exchanges, and flows.

Nothing we transmit is meant to remain fixed. And by the time they leave school, new questions will already have emerged. We do not deliver answers: we try, with them, to invent formulations that continue to open, to shift, to gently disturb – questions that remain fertile over time.

Even when built, buildings remain open; they are never truly finished. They continue to be questioned, reformulated by those who inhabit them. Heraclitus understood this long before us: ”you never step into the same river twice”. And so it is with each project, each gesture, each space: always the same, never identical.

This is not a method we apply. It is a state of mind. Staying alert, open to reformulation, accepting that forms may shift, that certainties may dissolve, that one’s gaze may change. Also embracing a sentence that quietly accompanies our way of working: ”Find what you love and let it kill you’’ – not as abandonment, but as intensity, as full engagement with what moves and transforms us.

It means accepting that what matters to us shapes how we think and act and accepting that it binds us, orients our choices, our tools, our ways of approaching situations.

It is a position:

neither romantic,

nor sacrificial,

but resolutely oriented.

To find what truly matters, to hold onto it, and to let that orientation reorganize our practice and our way of reading the world.

All the best

Stéphanie and Alexandre