Learning versus Las Vegas

Matilde Cassani

The research on Las Vegas by Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi started in 1968, with students signed in Las Vegas Studio, at Yale University. The aim of the survey was to investigate the phenomenon of Las Vegas sprawl after the postwar period. As innovative analytic techniques to study the cities, Scott Brown and Venturi, […]

The research on Las Vegas by Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi started in 1968, with students signed in Las Vegas Studio, at Yale University. The aim of the survey was to investigate the phenomenon of Las Vegas sprawl after the postwar period. As innovative analytic techniques to study the cities, Scott Brown and Venturi, related directly to Kepes and Lynch’s previous studies, promoted through their students the use of photographs and videos, unusual methods related to architecture at that time.

Even the photographical approach was an experimental trial, the researchers broke taboos and founded their documentation by treating architecture as a phenomenon captured in images. They comprehended the strength of photography to witness the reality in a specific time, as Barthes and Sontag stated in their texts:

“The Photograph does not necessarily say what is no longer, but only and for certain what has been.”

“The Photograph’s essence is to ratify what it represents.”

“Finally, the most grandiose result of the photographic enterprise is to give us the sense that we can hold the whole world in our heads as an anthology of images”.

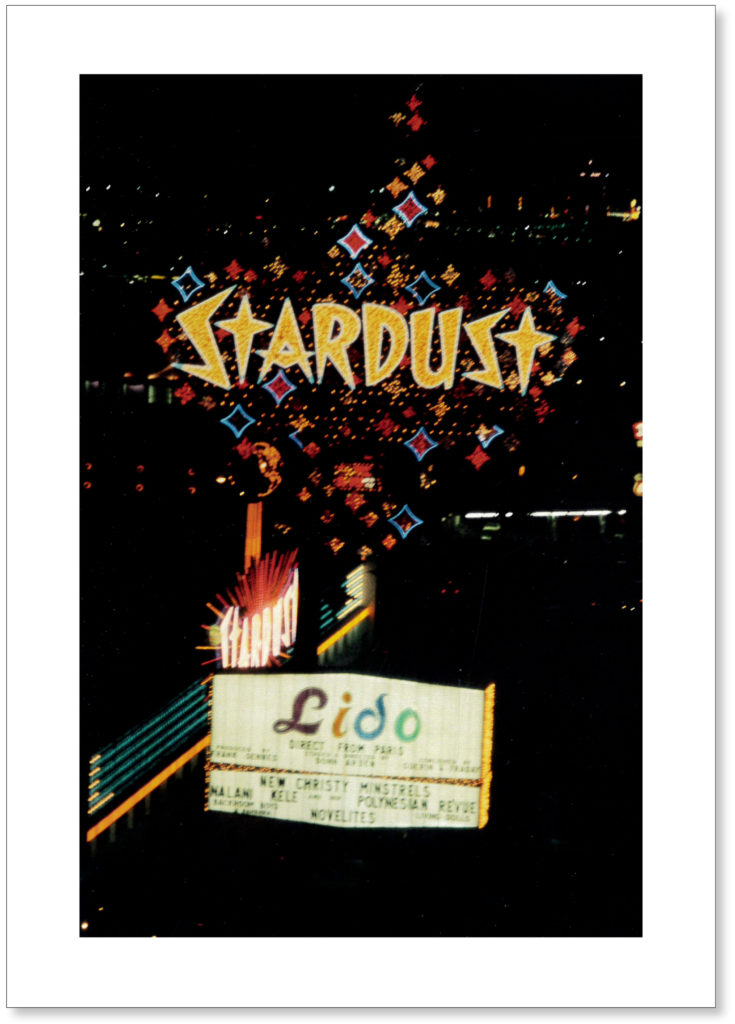

From the beginning of Learning from Las Vegas research, it was evident the intentional provocative and ironical coexistence of the meaning of Learning, as scientific photographical documentation, with Las Vegas, the unique protagonist captured in all the pictures, known as the iconoclastic city of fun where serious was dethroned. On one hand, Scott Brown and Venturi through photographs focused on architectural thought of action, on the here and now, capturing real images in a real time, producing a legacy of Las Vegas. On the other, Las Vegas was shaped in its real frivolous essence: the city of the escapism from the reality with its huge funny advertising billboards and nocturnal views overwhelmed by colourful lights. In fact, Scott Brown and Venturi suggested an unprejudiced view of Las Vegas, made of proliferation of billboards and nocturnal illuminations, and where the mechanisms of monetization and fun structures were promoted. As shown in most of the pictures, during night time Las Vegas expressed its playful nature, decorated by a massive number of lights, as Banham described in The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment: “What defines the symbolic places and spaces of Las Vegas—the super hotels of the Strip, the Casino-belt of Fremon Street—is pure environmental power, manifested as coloured lights.” Similarly, Archigram referred to Las Vegas as a pure electric architecture of light that was not attached to architectural form.

The nocturnal picture of Stardust was the perfect emblematic manifesto of the ludic spirit of Las Vegas. As most of the typical casinos-motels on the Strip built in the middle of 50’s, the Stardust casino architecture was neutral and its position was next to the highway. Paradoxically what appeared visible by driving cars from roads to Las Vegas was the casino’s billboard instead of the building itself. Once again, the Desert city expressed its humorous soul: Stardust sign inflected toward highway, it became the architecture of communication over the space and made the building itself hidden in the urban environment during daytime to totally disappear during the night.

Ironically, The Stardust 48 years old casino-hotel building became suddenly visible in the moment of its demolition in 2007, that became a paradoxical ritual of celebration: at 2 a.m. a gorgeous pyrotechnic spectacle of fireworks marked the 10-second countdown in front of the building before the explosives were touched off and the Stardust hotel concluded its existence in a dust cloud. The commercial persuasion of this big bright billboard reminded to the image of a carousel, a dreamy place far from the real world, a sort “Toyland” where to escape. Unfortunately, each dream has its waking up to reality and the Stardust was a photographed subject which captured a part of reality that can be observed and has its end, as Sontag stated in On Photography: “Photographed images do not seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it, miniatures of reality that anyone can make or acquire.” One more time the coexistence of Learning from Las Vegas reveals its controversies turning in the constant ironical contrast of Learning versus Las Vegas.

Stardurst, AA.VV. , Las Vegas Studio : Images from the archives of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, Scheidegger and Spiess, Zurich 2008.