What’s so basic about basic design?

Matthew Kennedy

“To design… is first of all to structure, and for me the study of structure (in the abstract) is the equal of that which has been known as basic design or foundational studies.”1 In the summer of 1957, William S. Huff returned to the United States a changed man. At the age of thirty, he […]

“To design… is first of all to structure, and for me the study of structure (in the abstract) is the equal of that which has been known as basic design or foundational studies.”1

In the summer of 1957, William S. Huff returned to the United States a changed man. At the age of thirty, he had just completed a year-long stint at the Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG) in Ulm, West Germany, then in just its fourth year of operations. Having received his architectural training at Yale under the likes of Neutra, Johnson, and Kahn—having already become a registered architect, in fact—Huff had secured a Fulbright scholarship to go to the HfG to study with the German constructivist painter Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart, who had joined the school’s faculty in 1954. His ambition? To discover “a more fruitful means of translating the two-dimensional experimentation of constructivist painters into three-dimensional architecture.”2 It was only grudgingly, then, that Huff acquiesced to the HfG’s insistence that he participate instead in the school’s obligatory Grundlehre (foundational course), then in its second year under the direction of Tomás Maldonado, the dynamic Argentinian theorist and designer who would become one of the school’s most influential figures.3 But the rigor of Maldonado’s curriculum, coupled with the intensity of the HfG’s intellectual and political climate throughout this period, proved to be an enormously galvanizing experience for Huff. Only a few years after his return, he embarked on what turned out to be a lifelong career in architectural pedagogy, the bulk of which spent exploring the boundaries of what has become more broadly known as basic design, a designation Huff himself eventually came to regard as something of a misnomer.

—

One would be hard pressed to overstate the impact of the Bauhaus on how design was taught in the twentieth century. Of the school’s myriad pedagogical contributions, the so-called Vorkurs remains arguably the most radical and widely emulated. The obligatory year of preliminary instruction, built around compositional exercises that were at once exceedingly rigorous and radically abstract, evolved with startling intensity over the course of the school’s short, tumultuous existence. The course was taught in markedly different ways by a succession of seminal instructors: Johannes Itten (1919-23), whose approach was rooted in the an unapologetically emotional expressionism and the generation of “contrasts”; László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers (1923-28), who began integrating new tools (notably the camera), a preoccupation with light, shadow, and transparency, as well as a distancing of the curriculum from Itten’s expressionism; and finally Josef Albers as sole instructor (1928-33), whose tenure shifted the course as close as it had yet come to the pursuit of “form that exists for its own sake.”4 Despite these shifting priorities, the Vorkurs nonetheless managed to achieve a certain consistency of effect: to destabilize newly arrived students’ expectations of what it meant to create (“unlearning,” in Itten’s parlance), to disabuse them of previous points of cultural reference, and to disorient them sufficiently that their thinking might be more effectively restructured around form, light, color, texture, and other perceptual concerns.

Versions of the Vorkurs would go on to be implemented by admirers of the Bauhaus’s paradigm-shifting reputation throughout the world, and in some cases even implemented by programs who attested to resist the tenets of the Bauhaus model.5 Most importantly, its lessons were also carried forward, probably to more pronounced effect, by many of the instructors and students who were scattered by the school’s closure in 1933, who went on to teach in (and in some cases, to establish from the ground up) forward-thinking programs of design education throughout the world. Indeed, far from being a settled matter, experimentation with the substance of what would, in time, become more broadly known as “basic design” continued at the various self-proclaimed successors to the pedagogical legacy of the Bauhaus (more than one of which had the advantage of being publicly “blessed” by Walter Gropius). Moholy-Nagy built upon his earlier curriculum in Chicago, first as director of the “New Bauhaus” (1937-38) and later at the School of Design (founded 1939, now the Institute of Design at Illinois Institute of Technology), where he oversaw a more tactile, materials-oriented “basic workshop” until his premature death in 1946.6 Albers, meanwhile, continued what would prove to be a lifelong engagement with basic design—with notably fixations on color theory, Gestalt principles (especially the differentiation of “figure-ground”), and articulated surfaces—first at Black Mountain College (1933-49), and later Yale University’s Department of Design (1950-58).7

In August of 1953, Albers (along with Walter Peterhans and Helene Nonné-Schmidt) took up a visiting lecturer position at the newly established HfG Ulm. Max Bill, founding rector of the HfG and a former Bauhäusler himself, had opted to base much of the new school’s curriculum on that of its famous predecessor, and had subtly rebranded their year-long basic course as the Grundlehre. It was the job of Albers, Peterhans, and Nonné-Schmidt to help orient the HfG’s inaugural cohort vis-a-vis a series of preliminary exercises, after which Bill and other HfG faculty took over for the bulk of the year. This system was repeated the following year (1954-55), by which time Maldonado had joined the faculty. He would go on to oversee the Grundlehre curriculum beginning in 1955-56. Though his approach was justifiably most indebted to Albers, whose lessons he had the advantage of observing firsthand, Maldonado gradually integrated lectures on the newest developments in topics including symmetry, topology, semiotics, and ergonomics into the Grundlehre curriculum (though these were always kept separate from the exercises themselves). This was, notably, a break from Albers’s previous insistence that to inject outside bodies of knowledge into the basic design curriculum would undermine the output (Albers famously discouraged his students from reading books during their participation in the Vorkurs).8

It was this most contemporary and theoretically rich interpretation of basic design that Huff encountered upon arriving in Ulm in September of 1956. Quite by accident, Huff would locate in Maldonado’s teaching everything he had hoped to discover in the work of Vordemberge-Gildewart: namely, a set of lucid compositional principles from which to attempt to suss out new forms of architecture. It is clear from later developments that Huff’s responses to these exercises must have left a strong impression on Maldonado (more on this later). It is equally evident that Huff became utterly convinced of the merits of his teacher’s pedagogical approach and theoretical position, a conviction that may have owed as much to Maldonado’s leadership through what proved to be the most turbulent year of the HfG’s brief history as it did with the efficacy of the Grundlehre exercises to the teaching, or the production, of architecture.9

From 1958 to 1960, Huff worked full time in the Philadelphia office of Louis Kahn, where he dedicated most of his time to developing the headquarters of the Tribune-Review newspaper in Greensburg, Pennsylvania (1958-62).10 At the same time, he began a campaign to generate interest in the establishment of a basic course in the mold of Maldonado’s Grundlehre in the School of Architecture at Yale, but by this juncture Josef Albers had firmly established himself in the adjacent School of Art, and had even been induced in 1957 and ‘58 by Paul Schweikher, then chair of the architecture program, to teach a course in “structural organization” (which, according to Huff, differed from Albers’s typical basic course in name only).11 Huff’s proposed program may well have been deemed redundant by the school’s leadership from the outset—they already had arguably the seminal innovator of the Bauhaus Vorkurs; why would they need a Grundlehre, too? Not yet defeated, and with Kahn’s encouragement, he developed a Maldonado-indebted syllabus and proposed to teach a basic course himself at the University of Pennsylvania, but was met with indifference from the administration despite his famous mentor’s backing. Finally, in 1960, Huff got the opportunity he had inadvertently sought out: he was contacted by Schweikher, who had just accepted a position as head of the School of Architecture at Carnegie Institute of Technology, in Huff’s native Pittsburgh. An instructor at Yale when Huff was completing his thesis, Schweikher was familiar with the younger man’s thinking, and with the fact that he had studied at an increasingly famous HfG. Now, ostensibly having heard about his former student’s failed proposal for a basic course at Penn, Schweikher offered Huff a place on the faculty at Carnegie, and with it, finally, a chance to bring the Grundlehre to America, though quite contrary to his original intent, and at the considerable expense of his own time and energy. Although Huff would continue to work intermittently for Kahn for another two years (until the completion of his current project), the better part of his efforts would now shift—permanently, it would turn out—towards design pedagogy.12 “Suddenly, sheer chance had veered me far off the course of my original intent, merely to spread the word in the States about a consequent course of a progressive school of design. I had stuck out my neck; my head was on the platter.”13

Huff taught at Carnegie from 1960 until 1972, a period during which he facilitated the invitation of Maldonado, Bonsiepe, and other central figures from the HfG to visit as guest lecturers. Maldonado returned the favor. From 1963 until the HfG’s dissolution in 1968, Huff would also return repeatedly to Ulm to teach basic design. By 1963, however, a number of key changes had occurred. First, the HfG had weathered another storm and emerged intact but yet again transformed. Horst Rittel and likeminded faculty who had arrived during Maldonado and Aicher’s push for the “scientification” of design, and whose line of thinking was above all methodological, had largely dictated the direction of the HfG from June 1960 to December 1962.14 Maldonado and Aicher fought to regain control of the school, reasserting design, not an ever-more sophisticated methodology (or worse, as they saw it, “methodolatry”), as the intended focus of the HfG.15 16 Aicher and Maldonado, now rector and vice-rector respectively, set about adjusting the curriculum to put things back on track. Responding to the lessons learned from this most recent challenge, changes to the curriculum were set in motion that would bring an end to the unified Grundlehre, such that students could for the first time enter one of the specialized departments from the moment of arrival. Instead, they would encounter a modified Grundkurs in their first year that was tailored to the particular mediums, materials, and methods of their chosen course of study. Huff, for his part, taught in the Visual Communication and Building departments. By this time, both Albers and Maldonado had begun to realize the suitability of “basic design,” in all of its complexity, as a potent realm for advanced studies. In other words, there was a tacit admission among the discipline’s innovators that there was, perhaps, nothing especially basic about “basic design.”17

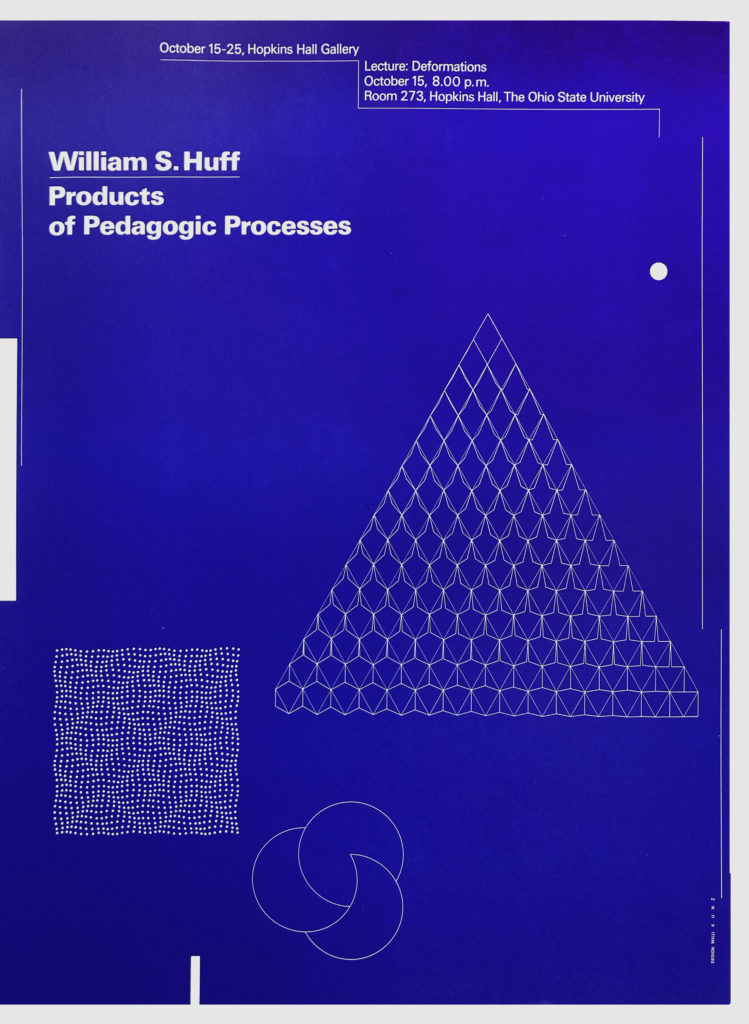

Huff’s exercises in both schools were heavily indebted to those he had confronted as a student at the HfG, and so Maldonado’s (and by extension Albers’s) concern for Gestalt theory remained embedded in his approach, including exercises using raster modules to produce matrix-like compositions that call to mind the popular Optical Art of the period.18 Huff would further develop Maldonado’s parquetry assignment into something more sophisticated: the so-called “Parquet Deformation” exercise, which focused on two-dimensional transitional geometry, challenging students to deploy advanced principles of symmetry (twofold- and fourfold mirror rotation symmetry).19 20 The parameters of this exercise were so thoroughly conceived that as early as 1961, students were achieving results that were every bit as sophisticated as those executed some thirty years later.21

Huff taught at the University at Buffalo SUNY from 1974 until his retirement in 1998, focusing predominantly on an optional basic course for “pre-architecture” students, and a thoroughly conceived, collectively instructed first-year architecture studio curriculum that shows strong signs of his influence.22 By 1985, however, Huff had lost his enthusiasm for teaching introductory architecture courses, shifting his focus to a graduate course in which students did exhaustive studies for a “new experimental school of architecture,” documenting historical references including the HfG. Later, seemingly in keeping with Maldonado and Albers’s earlier realization, he established a graduate level basic design course, hoping that these more mature and technically adept students would gain as much from the instruction as he had during his brief stint at the HfG decades earlier.

Huff’s desire to extract from basic design some manner of organizational values for the practice of architecture, so lucidly expressed in the immediate aftermath of his first encounter with Maldonado, seems to have waned over the years in favor of a conviction that basic design, as an autonomous, syntactic discipline, more than warranted his full attention. Though some echoes of basic design — the Bauhaus Vorkurs, the HfG’s Grundlehre, and others — may still be found in the instruction of architecture today, it is somewhat perplexing that one of its most vocal champions left it to a new generation to focus more emphatically on explicitly architectural outcomes of what Huff himself acknowledge, at its very core, to be a study of structure, not only perceptual, but also physical.23 Perhaps the challenge of “bridging” the chasm between abstract, non-applied design, and applied design, so central to Maldonado’s thinking in the 1960s, which Huff himself acknowledged, proved to be too much to surmount.

It is not difficult to project how the principles of Huff’s largely two-dimensional exercises—and the structural, geometric, and by extension spatial agility students ought to have extracted from their execution—could have been applied to the realization of remarkable architectural outcomes.24 It is therefore somewhat perplexing, in light of the obvious architectural potential of applying these principles to three-dimensional structures and the resonance such an approach would seem to have with the building systems-oriented pursuits of the HfG’s Department of Building (as clearly indicated by the fact that Huff was among the teachers of that department’s Grundlehre on numerous occasions), that he so stubbornly resisted such a step throughout his career.25 Or it would be, at any rate, if not for the fact that he himself responded to this apparent contradiction.26

“I have dealt all along, as Albers put it, purely with form that exists for its own sake, in the confidence that immersion in formal content alone—devoid of cultural, referential, or assistive, even physically characterized overtones—can unleash the sensory capacity. I speak now for myself. My overarching objective has been to elevate, without inordinate distraction, my students’ mastery of their own innate aesthetic acuities.”27

If anything, Huff’s contributions to the further development of basic design, as well as his efforts to serve as a conduit from Ulm to American architectural academia, hint at a fundamental truth: that such innovations as the Bauhaus Vorkurs rarely end with the dissolution of the institutions that gave birth to them. Rather, they scatter and evolve, at times beyond recognition, in response to new constraints. With this in mind, “radical pedagogies” must be understood as a fundamentally recursive phenomenon.

Huff died at the age of 92 in January 2021. In the absence of one of its most vocal proponents, the question persists as to what this often misunderstood field of “basic design,” so central to the foundations of twentieth century design pedagogy, may yet have to offer students of architecture in the twenty-first.