From Students to Comrades

Charlotte Grace

In From Allies to Comrades,1 Jodi Dean traces the term “comrade” to its etymological origins in the word camera meaning room, chamber, or vault. A structure, then, which forms and holds a space, soon becoming a vessel to capture the light. The camarada becomes they who share your room, they who reproduce its space both […]

In From Allies to Comrades,1 Jodi Dean traces the term “comrade” to its etymological origins in the word camera meaning room, chamber, or vault. A structure, then, which forms and holds a space, soon becoming a vessel to capture the light. The camarada becomes they who share your room, they who reproduce its space both next to you and with you, physically, socially, symbolically. In Dean’s words, ‘Comradeship is a political relation of supported cover’.

In my work, I consider pedagogy in light of comradeship and its sister concept, solidarity. I read solidarity as the social and spatial practice of making-room, of building positions that reach beyond the self and towards others. Solidarity, then, nurtures comradeship, and vica versa. Each form reproductive relations that allow for their proliferation beyond the proximate. This proliferation builds movements. As an educator, I am tasked with developing and nurturing a form of “reason” among students and binding this “reason” to the production of, in the case of architecture school, socio-spatial knowledge and practice; in other words, I build positionality in the making and re-making of room(s).

In the words of bell hooks, who feminises her concept of comradeship and solidarity into the form of “sisterhood”: ‘theory is not inherently healing, liberatory, or revolutionary. It fulfils this function only when we ask that it do so and direct our theorising towards this end.’ Similarly, scholars involved in feminist and decolonial struggles across the world find themselves exploring ‘methodology as a site of struggle’; it’s not what you do/ know, it’s how you do/know it, and it’s not from which position you do/know it, it’s towards which horizon you push it.’2 I ground definitions of reason in solidarity by emphasising the embodied and the lived as “reason” and by rejecting the (re)production of hegemonic reason by the default of dominant subjectivities.

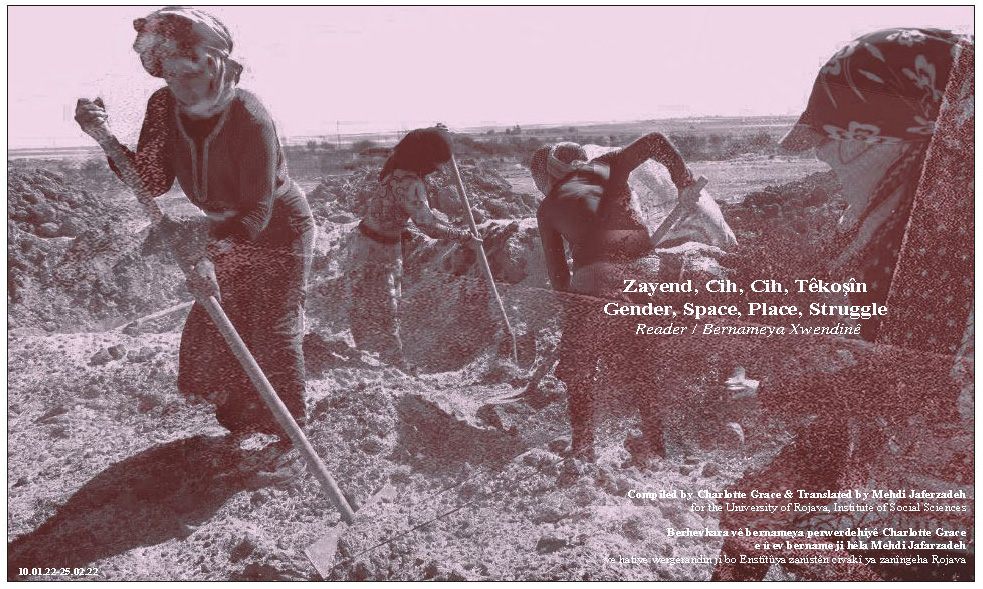

Front cover of Gender, Space, Place, Struggle module Syllabus (2022). The image shows the construction of Jinwar Womens Village in Rojava.

Jinwar members were both guest speakers of the RCA Solidarity Lecture and guest students on the University of Rojava course.

Translating this into an architectural context, how as spatial makers do we produce this space in which we become/reproduce comradeship? We have a rich spatial language through which to think through comradeship, but, as spatial practitioners, can we begin to form a spatial contribution to help strengthen social movements?

My work draws on existing thought on Social Movement Pedagogies together with emergent thought on Critical Solidarity, Fugitive Study and Mutual Aid, all of which bring Haraway’s seminal work on Situated Knowledge (1988) into paradigms of social struggle.3 In each of these frameworks, partiality and reason are confronted not only with feminist, queer and decolonial reworkings of subjectivity and knowledge, but also the ways in which one can act with-, for- and through an understanding of, a making-space for, the “other”, a looking-with rather than a looking-for, a framing-with rather than a framing-of.4 Building on this, I also bring in Helen Hester’s work, which looks to invert common notions of alienation. Hester argues that alienation is not always defined by a distancing from our actions, experiences and neighbours. Instead, alienation can bring us together as an active site of struggle; a position from which an intersectional empathy, reason and agency can meet and push towards emancipation. Hester proposes a “situated solidarity” as a ‘precondition for processes of careful solidarity building’ between people, species, and life-forms. By situating solidarity when making-room, I believe we can build a relational and polydirectional commitment to political movements – spatially conceptualised by Hester as a site beyond sight – one that is critically aware of institutional affordances and deploys them at the service of emancipation rather than extraction.5

These concerns inform my ongoing pedagogical practices at the Royal College of Art (RCA), London and the University of Rojava, Kurdistan (officially Northern Syria). Resisting the idea of personal or professional growth, I try to find ways in which pedagogical frameworks can push for collective growth in the production of socio-spatial knowledge – within and beyond the institutional form and, in-turn, towards methodologies oriented in “situated solidarity.”

At the RCA, I teach Embodied Knowledges and Urban Struggles for the recently-formed MA City Design, in which subaltern, marginalised and activist knowledges built in struggle are foregrounded as the lens through which any formalised spatio-political theory is to be read. We focus on diasporic social movements across London and decolonial struggles in Rojava, Chiapas, and Palestine, where our design studio is based. The module holds regular Student-led seminar sessions in which academic, disciplinary and/or journalistic texts are always brought into the room with anecdotal, informal and experimental voices, namely:

a) materials produced in the wake of struggle such as zines, call-outs, manifestos, plays, games, evidence, testimonies, counter-maps, and

b) perspectives and positions born of those who struggle, as-found in journals, music, testimony, photographs, protocols, strategies and dialogues.

Our routine meetings are peppered by intensive, 2-day workshops with campaign groups, activist projects and unions in a range of institutional, organisational and community settings. For students, these workshops explore how our source material hits the ground: how it is lived, embodied and fought for/against. In resistance to formalised educational structures and commitment to the embodiment and situation of knowledge, workshops take varied forms and locations from eating together with a question, walking alone/together with an idea, playing games to enact and experience cycles of political strategy, to live-chatting as we screens something online, to reading and rehearsing dialogues and scripts out-loud. In collaboration with our guests, we build socio-spatial representations and articulations of their struggles by developing maps, archives, designs, prompts and props that can offer material and discursive contribution to their work.

‘If you want to learn about movement building, get yourself outside involved with people that are building movements. That doesn’t mean don’t read books, or don’t talk to people with all kinds of intelligences. It does mean, get out, get involved and get invested.’ 6

In a similar vein to Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s statement, RCA students take on both the birds-eye and worms-eye view of research. The birds-eye swoops above and around knowledge landscapes. Alone, it lends itself to projects of superiority, surveillance and pseudo-objectivity. If we, alongside the elevated overview, also swoop down into the earth, we invest in it like the worms that process and aerate the soil, facilitating growth by making fertile ground as they move through it.7 Doing both keeps our focus in shift, occupying multiple and marginal positions; we both blur and sharpen methodological concerns, challenging social and spatial notions around perspective, scale, context, and relation.

Parallel to my work at an elite Western University like the RCA is my role at the revolutionary University of Rojava, founded in the wake of the 2014 Rojava Revolution. To put it briefly, the Rojava revolution is a decolonial, feminist (though Jineology is the name given to Kurdish feminist thought) and ecological struggle for self-determination which rejects the very concepts of the nation-state, territorial borders, and hierarchical structures that have defined civilisation since its emergence, notably in the Kurdish region of Mesopotamia. The Rojavan revolutionary movement sees education, like hooks, as ‘the practice of freedom… a way of teaching that anyone can learn.’ The university brings into its ethos the principles of the Rojava Revolution, Jineology, and emancipatory forms of knowledge. There, I teach socio-spatial thought and practice to the first MA Social Science cohort; our collective aim is to nurture concepts, methodologies and projects through Rojavan revolutionary frameworks. My students are, to varying degrees, protagonists of the revolution, each engaged in communal, political and military organisation as individuals and students.

Our collaboration is wide-ranging; it began with the translation of relevant socio-spatial texts into the historically-suppressed Kurdish language as a form of solidarity work. These texts were compiled into our core syllabus; they comprise radical academic and literary texts, manifestos of sister struggles, and excerpts of my own work on Rojava. Rather than being laid-out, the texts are a starting point for debate, critique and nurture in relation to the Kurdish geographical and political context.

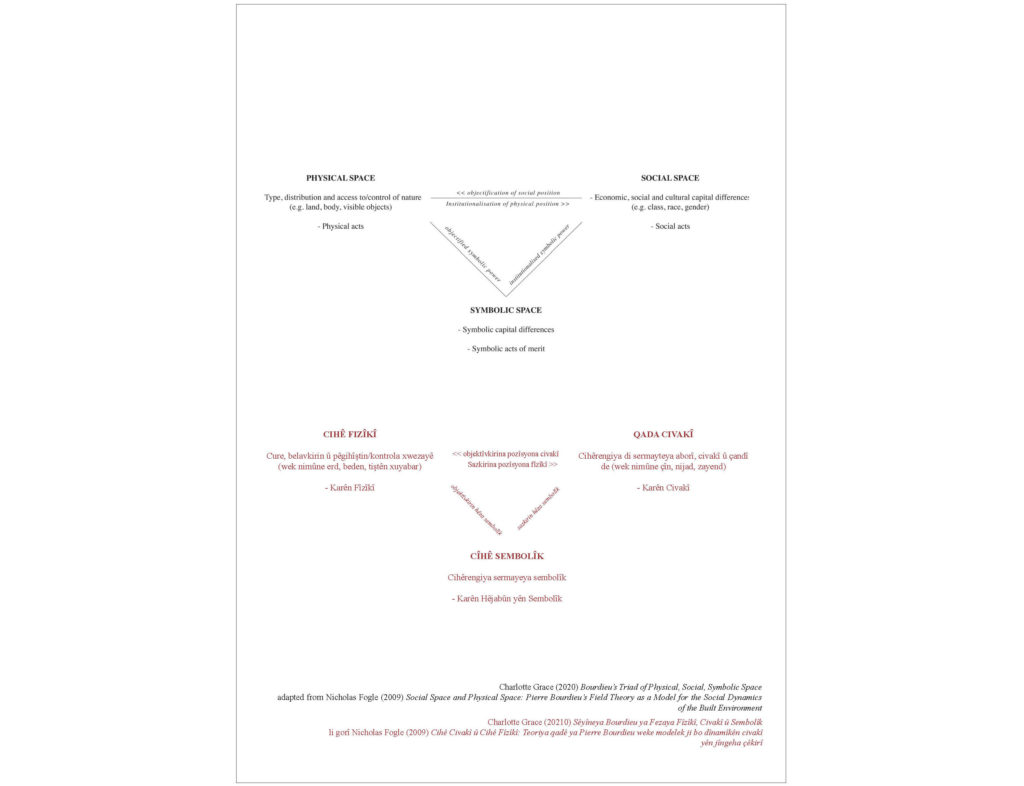

For example, we confront Bourdieu’s conceptual triad of physical, social and symbolic space – a concept that itself emerged partly from study of the Algerian Kabyle community during a period of anti-colonial struggles – with Kurdish liberation leader Abdullah Ocalan’s socio-spatial mantra ‘we must remove the ziggurats from our minds’, whereby this early-civilisation tiered architecture is said to have encoded the submissive and hierarchical human mindset.8 We put these in the room with Zapatista Thought on ownership, labour and liberation, epitomised in the phrase ‘the land belongs to the tiller’, and invite bell hooks’ work on domesticity, resistance and reproductive labour,9 and Jinwar Women’s Village and the Women’s Defence Units theorisation of self-defence, territoriality and the (re) production of free life. We also examine the politics of spatial representation as-seen from the students’ lived perspectives, confronting the Map of Greater Kurdistan and historical framings of the “vernacular” home as both malleable and contestable pieces of evidence in conflicts over individual and collective self determination.

As the course progresses, students engage with literature on visual methodologies in relation to decolonial and feminist thought, before going into the field to explore the spaces around them that are of personal (and) political importance. They visualise and analyse – in photographs, sketches, etc. – the physical, social and symbolic aspects of their everyday lives at a range of scales and sites. They draw their body in relation to the spaces around them, tracing the connection between space, social struggle and subjectivity. And they map the reproductive labour(s) done with and through space by themselves and those around them, noting shifts and endurances since the revolution, and how this might still be redistributed and redesigned in service of the region’s revolutionary claims. This activation of the future within socio-spatial critique carries their concerns towards a horizon, to what can still be done. As the emergent protagonists of the Rojava Revolution, students are empowered to facilitate socio-spatial understanding and critique in their communities, leaving the door to the room a little open.

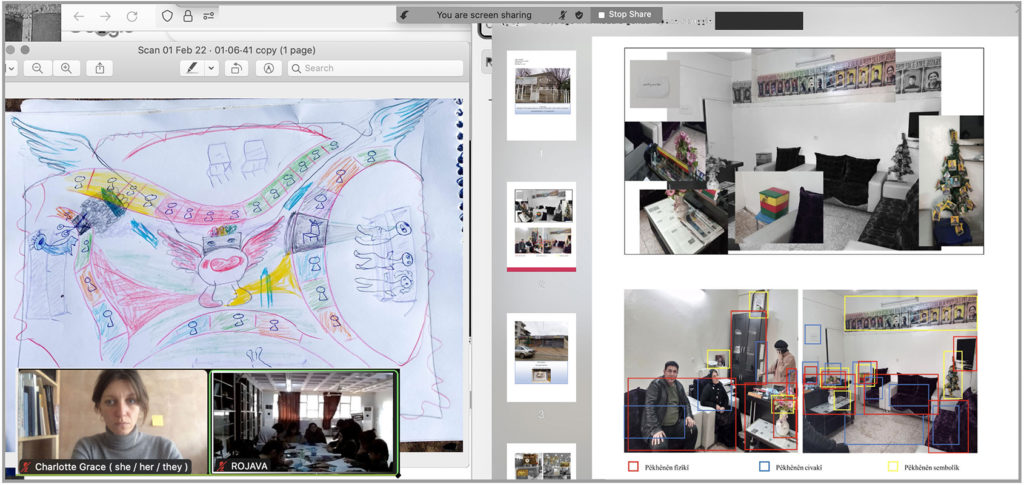

Page from the syllabus showing Bourdieu’s conceptual triad of physical, social and symbolic space translated into Kurmanji.

These two classrooms meet each other in the form of Solidarity events online. These public and private, direct and indirect interactions use simultaneous translation, synchronised exercises and shared live documents to build a body of work between classrooms. Students position themselves by harnessing distance, transgressing institutional confines, and looking/acting both inwards and outwards. This nurtures an embodied and reasoned awareness of both situation and solidarity; doors are opened, each according to the need and the light that they capture.

In thinking through these parallel pedagogies as two sides of the same coin, you could say I’m trying to build comrades out of spatial thinkers and spatial thinkers out of comrades. We share a room and lend our lenses. If, as Marisa Belaustaguigoitia tells us,10 the classroom itself is a borderland, it is necessary, and indeed urgent, to see how this space and those within it are reproduced, traversed, held, and situated in solidarity. Like a camera, the classroom forms both room and lens to look towards an emancipatory horizon.

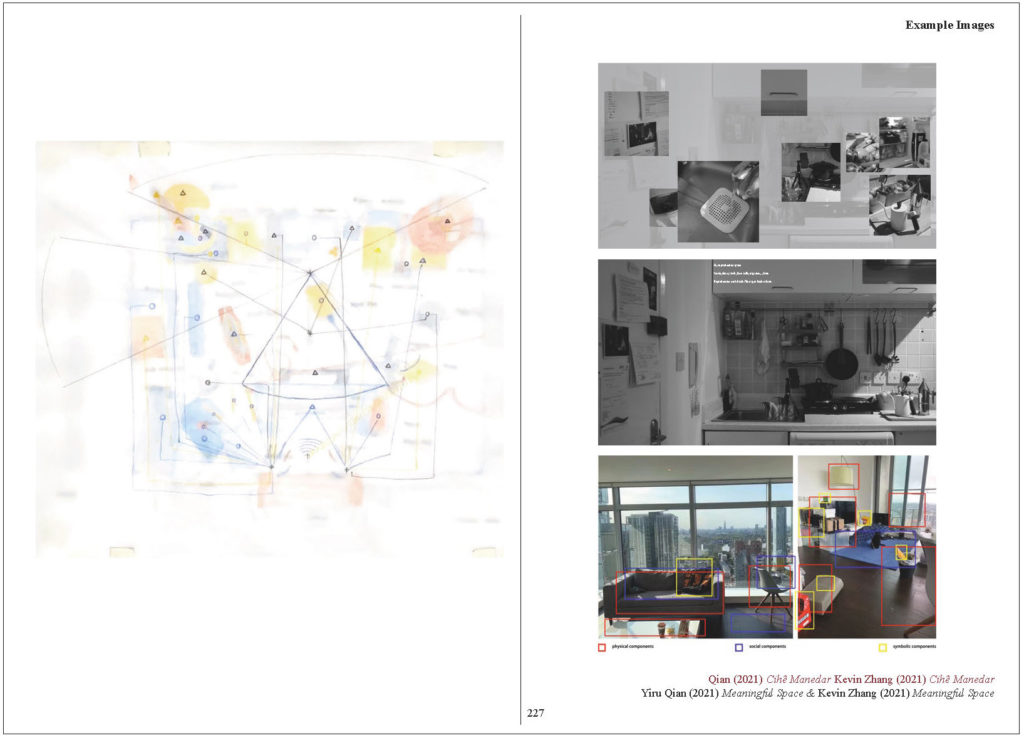

Excerpt from the exercise section of the syllabus. Examples of RCA students’ work from trial exercises run with MA City Design students are presented as precedent images for Rojava students to take inspiration from. The exercises show a mapping of reproductive labour in the home, a collage highlighting meaningful spatial components in the kitchen and an annotated image detailing physical, social and symbolic components.

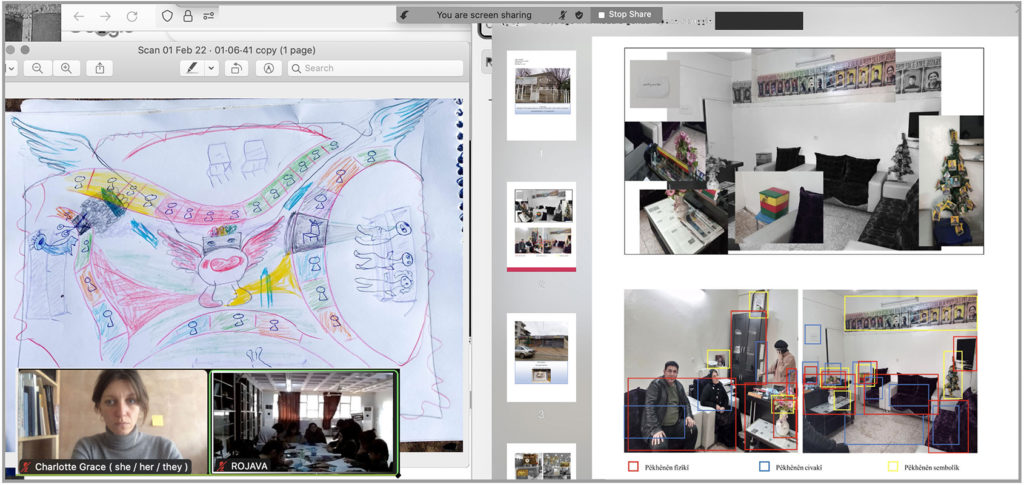

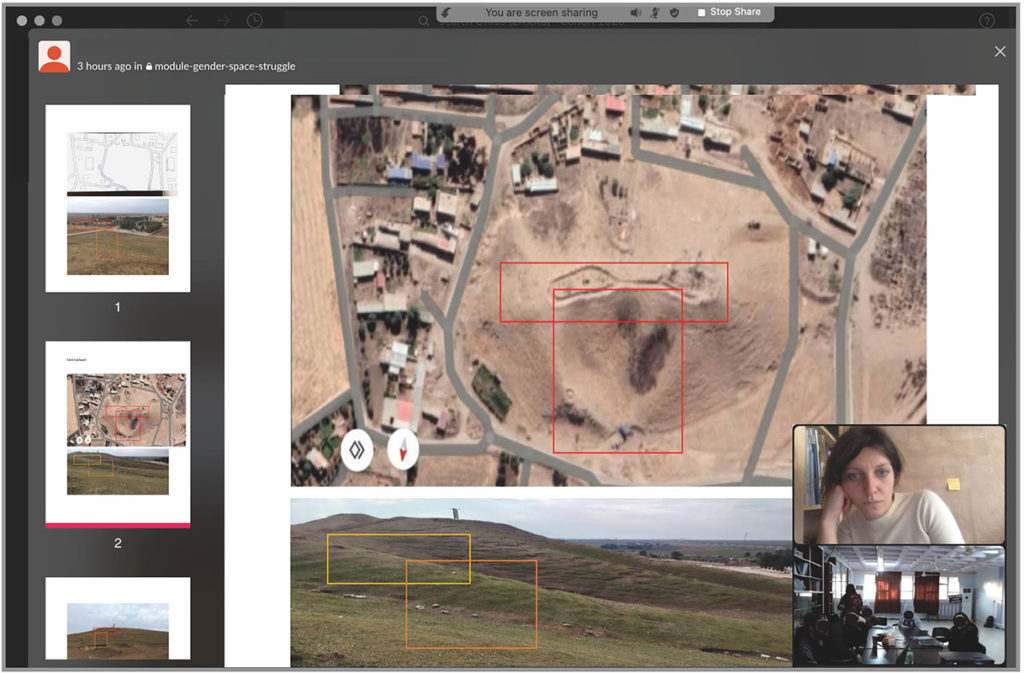

Screenshot from an online lesson at the university of Rojava during a student presentation. While some representational techniques have been blended, you can see how the precedent exercises by RCA students helped Rojava students. These images explore the Male Gel or ‘People’s House’, the central building of any confederalist commune in Rojava. Colour-coding, visual hierarchies and line quality are all considered, despite this being the first time these students produce spatial images.

Screenshot from an online lesson at the university of Rojava, during a student presentation. The images show a student’s exploration of a hill in their village, outlining its physical importance (military and wayfinding), social importance (Newroz celebrations) and symbolic importance (epitomised in the Kurdish mantra ‘the only friends to the Kurds are mountains’). The students’ understanding of territorial meaning was remarkably strong and reflective of their socio-spatial subjectivity.

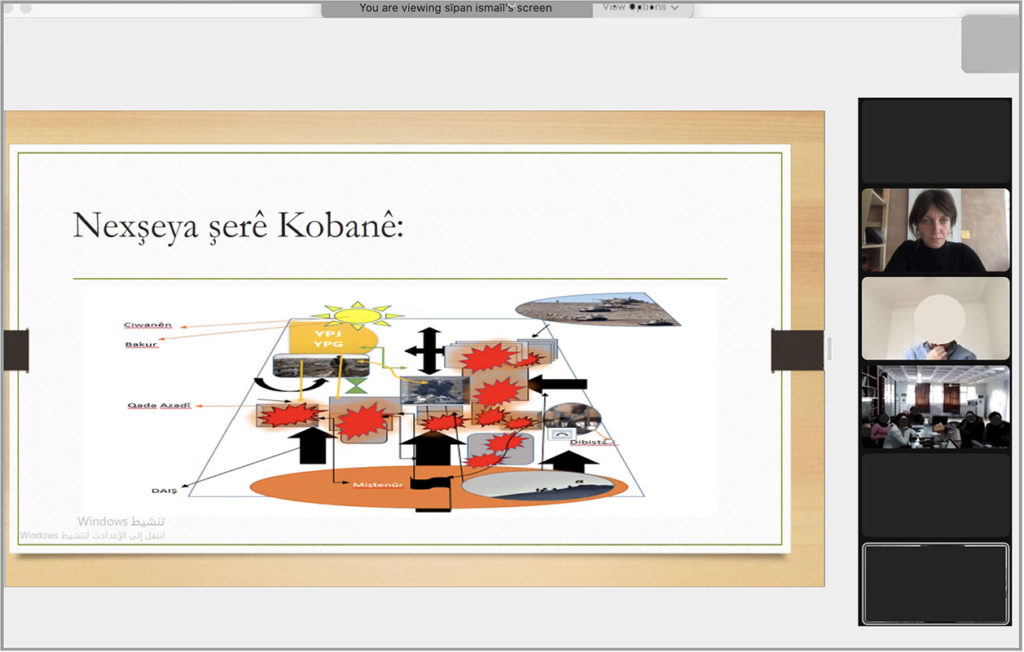

Screenshot from an online lesson at the university of Rojava during a student presentation. This image is a perspective diagram of the liberation of Kobane. The student mapped key explosions, military manoeuvres and sites of direct confrontation. They also showed a key hill nearby and a sun to the top left. As the student told me in the terms of our collective learning, this sun has multiple layers of meaning: the YPG and YPJ defence forces came from this direction and locals refer to the event as a time when ‘the sun rose in the West, Rojava means “west” in Kurdish, and the Kurdish flag is represented by a sun.