“Between Dreams and Knowledge”: Archiving the Summer Camps of Golan Heights

Jumanah Abbas

During the autumn days of 1988, a geography teacher was fired from the local Majid Al Shams high school for conduct of misbehavior. The alleged claim is that the teacher misappropriated ways of teaching, and of passing on knowledge and truth about the geographies of Golan Heights. Warned not to speak of the past, the […]

During the autumn days of 1988, a geography teacher was fired from the local Majid Al Shams high school for conduct of misbehavior. The alleged claim is that the teacher misappropriated ways of teaching, and of passing on knowledge and truth about the geographies of Golan Heights. Warned not to speak of the past, the teacher went ahead and taught the students about the geography of the area, the names of its valleys, its destroyed villages and lands.

Referred to as the Jawlan in Arabic, Golan Heights is internationally recognized as Syrian territory occupied by Israel. All levels of school education were registered under the Israel state’s central administration, and were consequently forced to adapt to a curriculum composed of highly tailored and censored subjects. Teachers are still obliged to follow the strict framework to this day.

The teacher’s position was that of retaliation and, ultimately, an act of non-cooperation. This act situated itself in a wider initiative; a group of teachers, parents, and students expanded the operations of the Golan Academic Association to combat the corrupt educational institutions across the Jawlan. One particular initiative sought to form alternative infrastructures of education through the format of summer camps.

Starting from 1985, summer camps began to operate annually with a communal agenda to change ways of learning about the Jawlan. These camps would, on one hand, oppose the state’s infiltration of local education systems and their curriculum of history, geography, arts and languages. On the other hand, the camps would provide alternative spaces to exercise resistance, as well as to actively refuse and unlearn falsified knowledge.

Above all, the summer camps would not follow the banking system of education that reinforces oppression, a process described by Paulo Freire in Pedagogies of the Oppressed whereby an educator regulates and orders knowledge.Here, in the summer camps, the position of the teacher was not to transfer knowledge to the youth, but to create different possibilities for the production and construction of knowledge. The teacher would not be a creator of a radical change in educational systems, but would mobilize that very change.

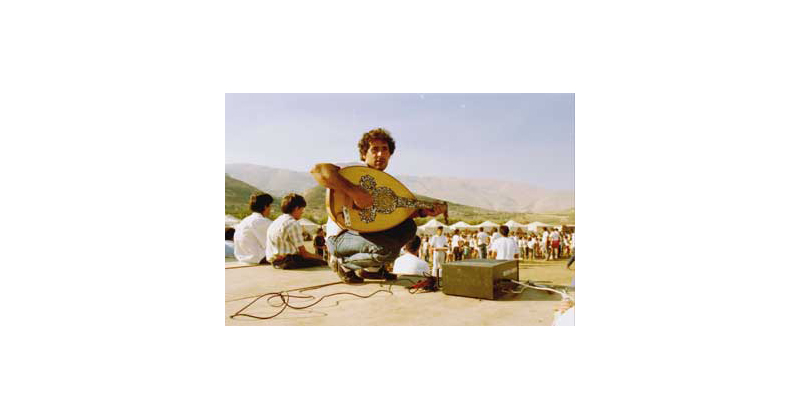

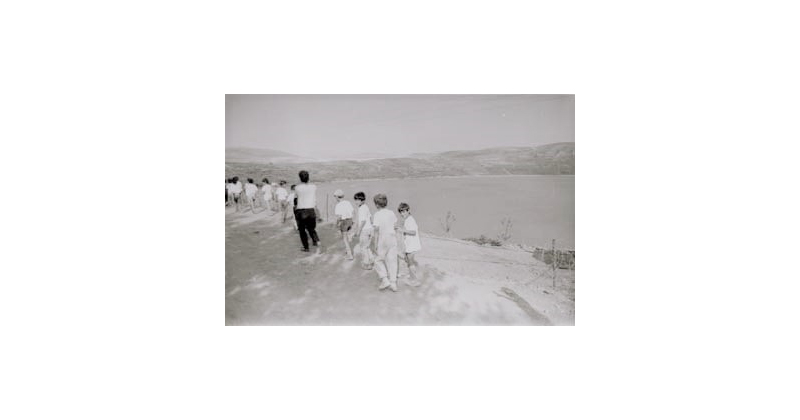

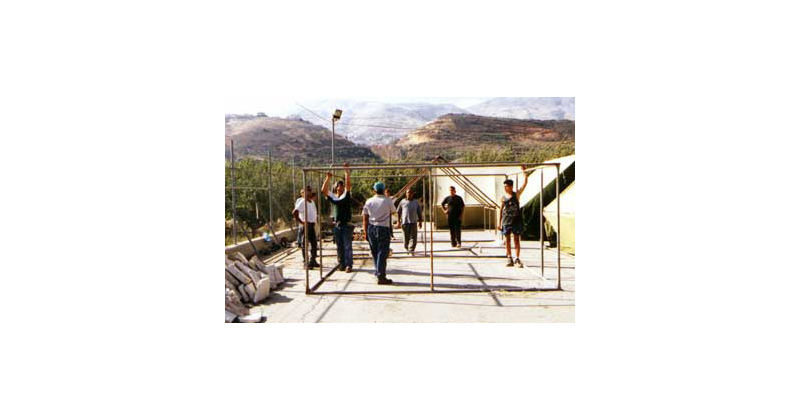

Acknowledging the histories of these spaces of learning, the photographic essay traces the pedagogies within academic infrastructures that visualized the landscapes of the Jawlan. Various images circulating in digital spaces reveal these urban spaces of learning and public life. While each image in the following selection captures the intimacy formed in these alternative spaces of education, the total collection of images reflect the politics of care, resistance and belonging that enlivened these non-institutional spaces of learning.

The images shape the urban imagination of the Jawlan, a land once enshrined by the memories of the people, but now largely unknown due to an underrepresented history. Just as the youth engaged with alternative spatial and temporal systems of education in the summer camps, following the ephemeral traces of these images requires a rethinking of spatial geographies to recollect stories and reconjure archives of Golan Heights anew.

Summer Camps as Spaces for Unlearning

While schools of the settler-colonial state continued to be physically constructed in the Jawlan landscape, these summer camps became spaces for the youth to exercise their rights and rediscover their own identities. Groups would gather to raise the Syrian flag and to sing the anthem of the summer camp. The following verse of the anthem projects a clear and powerful agenda:

Your glorious vision in the horizon, ورأيتك المجيدة في الأعالي

Will be woven by loyal men, بأفئدة الرجال سننسجها

Tomorrow with education, not ignorance, غدا بالعلم لا بالترهات

And with actions, not wishes, و بالأعمال لا بالأمنيات

The anthem reinforces the importance of education, and finding means to seek alternative knowledge. Another verse narrates:

On my left is the book, and on my right is the weapon,

بيسراي الكتاب وفي يميني سلاحي

And authenticity is on my forehead, والأصالة في جبيني

Between dreams and knowledge, وبين الحلم و العلم اليقين

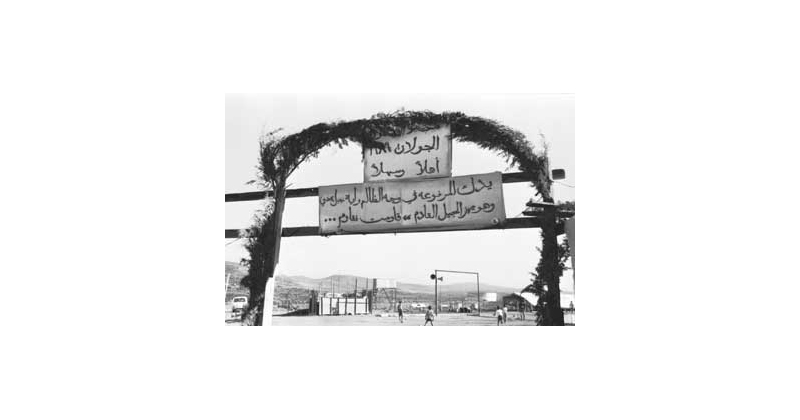

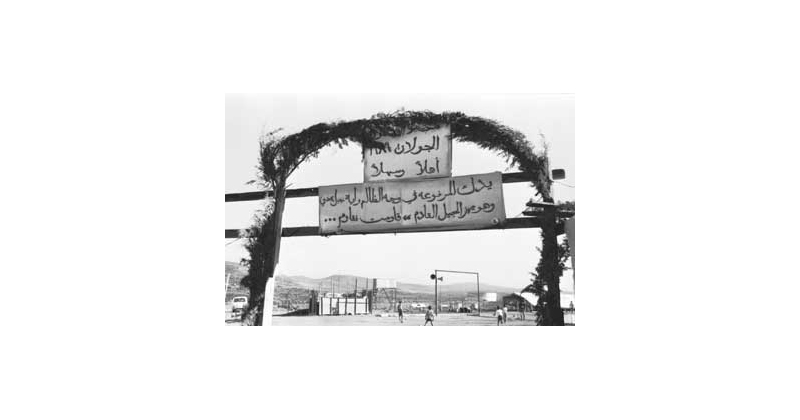

At the entrance of the summer camps a sign read “your hand raised in the face of the oppressor.” The text on the signage continues to project that the future of knowledge sharing about the Jawlan is in the hands of the youth. Welcoming young students to these camps, the entrance invited them to participate in the creation of a better, fairer and liberal environment; proving to these students that resistance was possible in the face of oppression.

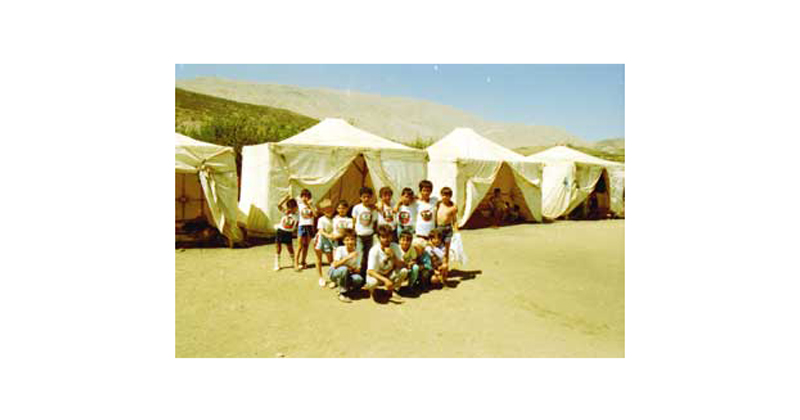

In each tent, young students would learn about the history and the urban geography of the villages, as well as the history of expelled families; their roots, traditions, and socio-cultural practices. Each tent had a similar set-up to a classroom yet housed varying information on the area; students would move from tent to tent to learn about the erased urbanity of the Jawlan.The tents were a visual and social reenactment of the destroyed villages of the Jawlan. The camps acted essentially as spaces for unlearning what was taught in the official schools.

The geographical location of the camps – between the two largest villages Masa’ada and Majd Al Shams – was set up to connect the two disparate areas. Collectively, the tents would represent and serve as a spatial microcosm of the erased lands of the Jawlan. A spatial reading of these camps allows us to reconsider common notions of space and time: the camps are neither political spaces of exception, nor spaces for the stateless. Instead, these camps produced multiple pockets of spaces for liberation.

Extending beyond the tents, the leaders of the summer camps would organize trips within and around the landscapes of the Jawlan. A documented trip to the Masa’da Lake shows a radicalized pedagogical progression in that the geographies of Golan Heights should be taught by physically being in the landscape. The purpose of these trips was not only to introduce students to the history of the Jawlan’s geography, but to imagine the patched-up terrain as a holistic land that belongs to the students and future generations.

Future Knowledges

Through alternative learning spaces, the community navigated between the inherent structures of power between the state and their freedom for creative education. Alternative education on areas of geography, lost architectures, arts and history would restructure and shape different ways of learning about the Jawlan lands and communities. Opposed to the official curriculum taught in schools, the summer camps’ pedagogies were new means of producing knowledge and gathering future knowledge to learn the history of the landscape.

Each year, the camps would run for the duration of the summer days and nights. The temporality of these summer camps reflected the community’s hope in the ephermatility of the occupation; each classroom set-up was impermanent, trips were sparse and the curricula were designed for a short timeframe. Years on, however, the occupation had intensified and cemented, and the temporality of the violence had become permanent. Dreams for the summer camps fell apart and years later in 2010, with the escalated tensions of a Syrian civil war outbreak, the camps stopped operating due to the community’s internal clashes about the future of the youth’s national belonging.

The summer camps of Golan Heights were once a space of learning and unlearning, which now has residues in the contemporary built environment. A reading of the histories of these camps can serve as an invitation to rethink through the politics of resistance beyond its alienation and, instead, to reposition the camps as spaces for actively practicing liberation. Archiving these images and stories has a central aim: to ensure a democratic shaping of curricula and academic bodies for future knowledge production. To follow these camps closely, and to learn what the students have been learning for and fighting against is to depart from reading the politics of resistance bound to public spaces and territories but, instead, to humanize the narrators of those who were oppressed, and of those who fought against the face of oppression with education and knowledge.

A Note from the Author :

My interest in alternative spaces of learning started during a course, Mapping Borderlands: Drawing from the Jawlan, taught by Nora Akawi in partnership with Aamer Ibraheem and Khaled Malas at Columbia University. We traveled to Jawlan and met with some organizers of the summer camps during which they shared their stories, lived experiences and images of the summer camps.

Jumanah Abbas is an architect, a writer, and a curator, working through an ecology of interdisciplinarity that architecture debates, concepts and dialogues engage with. Jumanah is part of ongoing collaborations with institutes, regional organizations, and universities: one was the “Mapping Memories of Resistance: The Untold Story of the Occupation of the Golan Heights” project in collaboration with London School of Economics, Birzeit University, and Al Marsad, Arab Human Rights Center in Golan Heights. The other was Tasmeem Biennial 2022, themed around Radical Futures, by Virginia Commonwealth University, School of the Arts in Qatar. She is currently working towards the realization of the upcoming Qatar Museums’ Quadrennial project, a multi-site art exhibition opening in 2024.