Pablo Garrido

emailing with Francisco Moura Veiga

Dear Pablo, I hope you are doing great! Back in 2014, I invited you to be a part of what would later become CARTHA. We were friends before and we remain friends still. But what I am writing to you about pertains to a precise interest among the many we share: publishing in Architecture. As […]

Dear Pablo,

I hope you are doing great!

Back in 2014, I invited you to be a part of what would later become CARTHA.

We were friends before and we remain friends still. But what I am writing to you about pertains to a precise interest among the many we share: publishing in Architecture.

As you know, this will be the last Cartha issue. It, in an assumingly self-referential manner, asks the question “what remains?”

Staying true to what we have always done with our titles, it has multiple readings: it can ask what stays after something else passes and it might inquire what remains is referring to, “remains” as a verb, “remains” as an iteration of a verb.

From the very beginning, when thinking about why we should produce books out of the online magazine’s content, we saw the physical object as a vessel for permanence: printed books are referenced, registered with a dedicated ISBN, stored in national libraries. The book would outlive the internet.

Since then, we have produced some books, both within (as the “Making Heimat” or the “On The Form of Form“) and beyond the borders of Cartha. So, as much as mine did, I am certain your relation to print has evolved: Your issue of Quaderns is an example of your take on the relevance, even influence of print over architectural thinking and production; as a result of your current teaching assignment at Weimar you are planning on producing a book on a specific design approach; in your practice with PARABASE, your library is a vital resource for any design act.

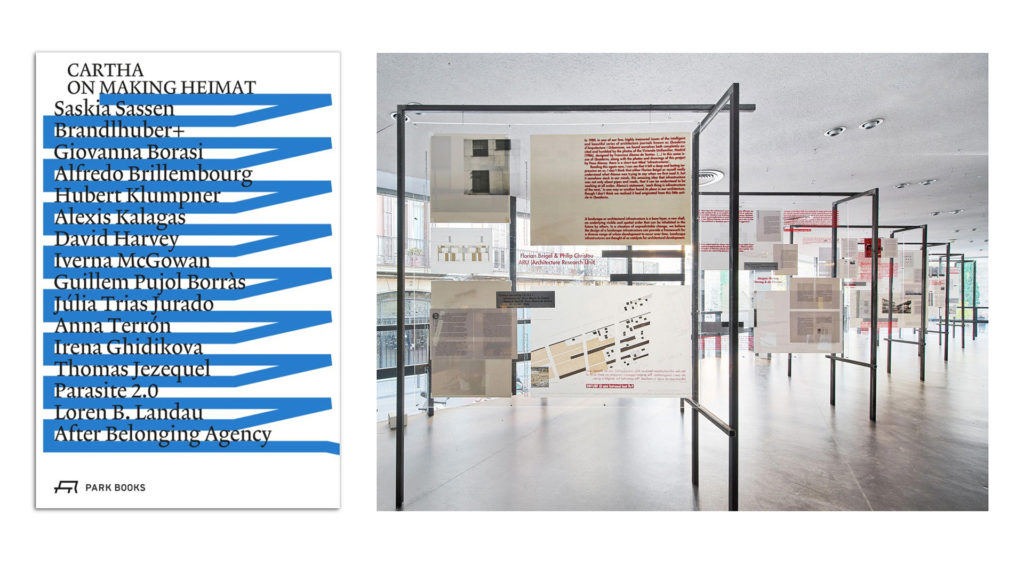

Left: “Cartha On Making Heimat”, Park Books, Zurich, 2017. Right: “Unveiled Affinities: Quaderns in Europe” exhibition and publication, 2019.

So, beyond these implicit acts of value attribution to books, I want to ask you to expand on them explicitly:

– Why should books be produced? For whom?

– How do these beautiful objects relate to the beautiful digital realm?

– Why invest the physical resources in objects that might, at the end, remain on a very national, very protected shelf?

Looking forward to your reply!

All the best,

Francisco

…

Hi Francisco!

I’m really happy that you’ve asked me to take part in this last issue… you know that Cartha has a very emotive side to me. It was somehow one of the first times where we could freely explore certain intuitions, affinities or interests we had in the broad field of architecture. The publication also acted as a pretext to start our own professional paths independently, besides our work in different offices. In any case, it’s been such a long journey since 2014 it would have been impossible to predict at the time where we are now.

Answering more specifically to what remains and to your concrete questions:

– Why should books be produced? For whom?

I’m not sure books should still be produced. Don’t get me wrong, I value them as physical objects, as a source of knowledge, even I somehow collect them, and obviously they have had a crucial role in my intellectual and professional development, but I’m not dogmatic about their presence in the contemporary world. I think books had a very clear purpose some centuries ago and nowadays, this same purpose, and maybe even additional ones, could be fulfilled by different types of media. In any case, I’m also Ok with continuing to produce books for the people who love them. I’m personally unable to program and almost to navigate on the internet, so that’s why I still produce books as a way to archive my research work.

– How do these beautiful objects relate to the beautiful digital realm

That is to me a critical question. We are currently reflecting a lot in the office on the connection between the physical and the digital realm and how to establish productive synergies between them. At this precise moment, we see that the digital realm offers a more diverse array of potential connections. Actually, we are very much interested in the possibilities of the so-called digital publication. We believe that therein lies a substantial, still unexplored, potential.

– Why invest the physical resources in objects that might, at the end, remain on a very national, very protected shelf?

Mainly because with the current mindset, and generalizing a lot, societies still perceive books and tangible objects as a much more durable and prestigious media. Almost as if the Alexandria Library never burned down. Operating within this specific mental frame, people tend to invest much more time and money on creating content that is meant to be published in the physical world, and therefore, last longer or forever. If these shared prejudices would disappear, I would question much more the production of physical goods that are intended to remain, as you say, in a very protected shelf.

How do you see the situation? Could you foresee a society that perceives digital media as permanent and durable as physical objects? I’m even starting to be a bit paranoid about my digital footprint.

Also, have your explored options of digital publishing with Voluptas or with a-Forschung?

Do you know any examples of successful digital publication? Besides of course https://www.e-flux.com/ and so..

Btw, I just found last afternoon on the internet Las Fuentes del Espacio of Prada Poole for just 30e, crazy. Will be in my shelf next time you pass by 😊

Looking forward to hearing from you soon,

Pablo

…

Dear Pablo,

Funnily enough, last week our publisher reached out to us with some aptly timed news: due to an optimization of their stock, they “have” to get rid of the large majority of the unsold copies of the four books we, Cartha, have produced together with them. They kindly offered us the opportunity to buy our books with a 90% discount and to offer the same deal to any contacts we might have in mind. They did not say what would happen to the books when we would not buy them so I asked; turns out books will be destroyed. So the one copy is stored at the national library of the country the publishing house is based at but the rest of the print run is left unprotected.

This directly refers to one of your questions it is very much aligned with a contemporary societal trend in which digital is presented as a safe depository for knowledge, one impervious to the natural material decay or to small accidents, such as forgetting a book somewhere, or larger incidents such as the burning down of Alexandria’s Library. I would argue that the current (constant?) “end of the days” mindset positions books pretty much as fragile and condemned: see the drive for trans-humanism by the cream of the 1%, so hilariously portrayed by Steve Carell’s character in “Mountainhead” or, more optimistically suggested in the brilliant series “Pantheon“. Is the internet forever? Not sure I want to touch this question with a 5-feet-pole…

Mountainhead is a satirical comedy-drama television film written and directed by Jesse Armstrong, 2025.

Something we are forgetting is a key characteristic of online digital: accessibility. A webpage is here, there, everywhere. A book not necessarily so. One of the tools I have been developing in the last two years at Voluptas is a web-based game to help students making the best out of the cognitive conflict they naturally encounter when working in group settings. There are two big advantages in this medium for this specific tool, (1) as it allows students from anywhere–given they have internet access–to be able to profit from it, while a physical game, be it as a set of cards, a board game or a book, would be way more limited. And (2), digital environments are “two-way” communication media: there is an interaction with the page that can be rigorously monitored used in order to a myriad of purposes. Imagine asking for readers to give such detailed feedback on their experience reading a book?

On the other hand, you are more prone to engage with something that you can see, that you can touch. The physicality of learning is not to be overlooked, as more than one take on learning has shown (this study by the Reading Research Structure of the University of Valencia is specially telling). A book is a precise, physical gateway to information in a way that a screen can never be for digital content. The dynamism and ubiquity of internet are the inescapable fast-tracks for a user’s feeling of being lost. This is not new: already back in 1970 Alvin Toffler spoke of “Information Overload” or “Choice Overload” in his sharp “Future Shock” book.

I come back to Cartha to address the website: who will read it when we finally kill our instagram? When there are no more events and when our books have been destroyed? What will the “real-life” queue be for leading anyone there?

Internet is like space: mostly empty when you do not know what to look for.

Enter the algorithm, Brahma as the universal, individual content curator, coming to you through any of your favorite media mogul outlet.

I am stepping into global media politics here, something I would rather avoid. I would be more interested in circling back to the specifics of publishing in Architecture.

Is the publishing medium a question of purpose: what do you want to say, to whom?

Or is it rather a broader question of relevance, of expectations?

François Charbonnet, drawing from Virilio’s notion of “projectile”, regularly tells his students to thing of a project as an idea thrown into the future: you can foresee its reach but you can’t know whether someone will pick it up.

Coming to something precise, how are you and Carla thinking of dealing with the knowledge you will produce together with the students both at Weimar and at the ETHZ?

Are you throwing it forward in any form?

Which form and why?

And who should pick it up?

All the best,

Francisco

P.S. – List of successful digital publications:

aeon.co

theguardian.com

At least according to my internet history…

Looking forward to holding the “Las Fuentes del Espacio”!

…

Hi Francisco,

Sorry for the late reply… holidays and submissions… you know the deal.

During this summer I’ve been reading the book by our friend Xavi Nueno on archives and libraries… there he states that from all the information Humanity has generated throughout its history, 90% has sprung up in the last two years. “In the past, we had to choose what we wanted to preserve for posterity, and only that which we considered truly valuable survived the judgment of history; but nowadays, thanks to the famous cloud, there is no need to choose and we can preserve everything. Thus, two opposing forces arise: the indefinite and unlimited growth of the library, and the warning about the danger of the past burying the present, about the risks of ‘excesses of the written word.’”

I’ve always wondered whether piling up architectural knowledge, be it historical, theoretical or technical, actually helps when writing, designing, or thinking. Coming from a Latin tradition, I used to think it was essential. But after working at HdM, I saw the value in staying unprejudiced, in the lightness and even the learned naivety behind some decisions. What about you? Do you feel this “backpack” of knowledge helps your work? Are you still adding to it, or trying to let go of things instead?

A paradox arises here. The discourse against publication is itself part of the humanistic tradition. During the Enlightenment, this impulse against the excess of books and information grew even stronger. After all, D’Alembert and Diderot’s Encyclopedia was nothing more than an art of reduction, a search for the synthesis of knowledge. And so we arrive at the paradox that “the only legitimate reason we write is because there are too many books. ”The library of Montaigne, for example, was far from the exhaustiveness of professional libraries. It was a more amateur library, precarious and imperfect. It is, then, a matter of creating a portable canon of knowledge, abbreviated, light, and mobile. One that could almost fit in a suitcase. Perhaps you could even reduce your library to just a few books to carry in a suitcase. In that case, which ones would you choose?

If the content we produced in Cartha makes it into even part of someone’s suitcase, I’m satisfied. If it turns out to be useful or enjoyable for a couple of people at a specific moment, that’s enough. In fact, I’ve found the greatest satisfaction in our work when I’ve seen that someone has actually made use of it, for whatever purpose that might be. Perhaps publishing remains one of the few ways to shift the conversation and redirect the focus, to claim a space usually reserved for those of the dominant class and the status quo. By launching a magazine, young architects can insert themselves into a lineage, a history, a discourse, and who knows, maybe to begin to transform it. I’m not sure we’re living in a more reflective era for publishing architecture books than before. “In your time, to the shame of reason, more was written than was thought,” wrote Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1771. How do you see this age of superficial constant scrolling? Do you feel more apocalyptic or integrated about it?

In any case, I still find it necessary to publish. At the University of Mendrisio, first as a student and later as a teacher, I’ve always fought for it, because I believe it’s essential to create the school’s journal of record. Education, after all, is not just about learning, it’s also about the cultural production and sharing of knowledge that a university generates as a whole. In fact, for the first issue of the Mendrisio Magazine, the editorial team asked me to contribute a text, and, funnily enough, I wrote about creating a new canon of references, one that was deeply personal and almost driven by pleasure.

But perhaps we can imagine future JSTOR-like platforms that go beyond metadata and tags for papers and articles. Almost like the way, in the 16th and 17th centuries, scholars across Europe began cutting, extracting, and annotating books with scissors. From the profanation of the book emerged the archive, a way of organizing knowledge that prioritizes visibility, openness, accessibility, and, above all, the de-hierarchization of content. This is the kind of approach we’d like to adopt for publishing the work we produce at the Bauhaus or ETH in the future: publishing in a way that connects and contributes to read across magazines, books, websites, Instagram accounts, video essays, digital catalogs, virtual exhibitions, territories, and ideologies. The goal is to take important issues and discuss them collectively, as one continuously contemporary magazine of architecture in progress. Do you think this enterprise is viable, or even positive?

Looking forward to hearing from you! And I won’t take that long next time to reply!

Abrazo

Pablo

…

Dear Pablo,

“The goal is to take important issues and discuss them collectively, as one continuously contemporary magazine of architecture in progress.”

This last sentence of your email perfectly nails down the purpose we had in mind at the genesis of Cartha. I have to say that, after 10 years, we now know it to be an impossible goal. Still, trying it is, to answer your question, definitely viable and surely positive.

For the last email of our “pen-pal” exercise, I found it fitting for us to share a list of 10 books which have had a lasting influence over our work, be it in editing, teaching or designing. No need to comment it as our previous exchange acts as such already.

Here’s mine, not in any particular order:

- “Collected Fictions”, Jorge Luis Borges

- “Cedric Price Works”, Samantha Hardingham ed.

- “Wer Plant die Plannung?”, Lucius Burckhardt

- “Sitopia”, Carolyn Steel

- “Disobey”, Frédéric Gros

- “Architectural Regionalism”, Canizares ed.

- “Scary Architects”, San Rocco 5, Fall 2012

- “Homo Ludens”, Johann Huizinga

- “The Function of Criticism”, Terry Eagleton

- “Society of The Spetacle”, Guy Debord

Looking forward to yours!

All the best,

Francisco

…

Dear Francisco,

Sounds great! Here is my list of 10 books:

- Object-Oriented Ontology: A New Theory of Everything, Graham Harman

- ABC of Reading, Ezra Pound

- The Weird and the Eerie, Mark Fisher

- Altermodern, Nicolas Bourriaud

- Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past, Simon Reynolds

- Unoriginal Genius: Poetry by Other Means in the New Century, Marjorie Perloff

- Metamodernism. The Future of Theory, Jason Ananda Josephson Storm

- Disordered Attention: How We Look at Art and Performance Today, Claire Bishop

- The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty, Benjamin Bratton

- Future Metaphysics, Armen Avanessian

PS: I’m adding two recent books in Spanish which I consider essential:

- El arte del saber ligero: Una breve historia del exceso de información, Xavier Nueno

- El mejor de los mundos imposibles: Un viaje al multiverso del reality shifting, Gabriel Ventura

I hope you like the list! You should buy at least the last two for Christmas!

Pablo Garrido Arnaiz studied architecture at the Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Barcelona, ETSAB and at the Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio, AAM. As an architect, he has worked at Foster & Partners, Miller & Maranta and Herzog & de Meuron. Since 2014 he was editor of Cartha Magazine with which he participated in the 15th Biennale di Architettura di Venezia, the 4th Triennale de Arquitetura de Lisboa and has published a series of books with Park Books. He was a Teaching & Research Assistant at the Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio and has been invited as guest critic at several Universities and as a tutor to several workshops and summer schools. He is co-founder of PARABASE, an international collective operating within architecture and urbanism with which he has help teaching positions at the Bauhaus Weimar and the ETH Zurich.