A Scenography For The Signal Intrusions

(ab)Normal

The first screen that the public experienced was undoubtedly the cinema screen. Film projection made it possible to reproduce and transport content by flattening the stage, making it two-dimensional and confined to the screen’s surface. In the early 20th century, a new type of architecture emerged, that of the cinema, which was somewhat distant from […]

The first screen that the public experienced was undoubtedly the cinema screen. Film projection made it possible to reproduce and transport content by flattening the stage, making it two-dimensional and confined to the screen’s surface. In the early 20th century, a new type of architecture emerged, that of the cinema, which was somewhat distant from the original model of the Odeon. It’s no coincidence that many movie theaters adopted the same name. The invention of cinema, therefore, represents a significant evolution in entertainment technology. Nevertheless, the invention of cinema technology didn’t bring about a paradigm shift in the design of entertainment space. Many theaters were adapted to accommodate screens and projections, effectively becoming proper cinemas.

The consumption of content essentially remained unchanged; the passive spectator who sporadically and collectively witnesses the performance or, in the case of cinema, the playback of entertainment content. Cinema, in other words, traditionally involves a passive audience with no interactive capability. The wall between the audience and the actors remains solid. The urban planning emergency of large indoor spaces, where communities collectively consume works written and directed by a group of intellectuals who educate and guide the cultural life of communities, is still in place.

Television completely disrupted this balance. Starting from 1928, cathode ray tube television sets, built following the design of inventor Philo Farnsworth, began to populate homes in the United States and Europe. In a few years, NBC in the United States and the BBC in the United Kingdom structured the first weekly television schedules. Living rooms, once inviolate spaces dedicated to family intimacy, became portals through which propaganda messages, advertisements, news, and in-depth programs were broadcast. Above all, living rooms became small dispersed audiences all over the Earth’s surface. The space that was once concentrated within large urban boxes was segmented into countless domestic “tribunes.” The cathode ray tube technology initiated a process of public life penetration into the private dimension of the home, which today occurs within digital devices. Television is the first device capable of altering the geography of domestic space, a process that, thanks to smartphones, renders domestic zoning completely anachronistic.

Entertainment architecture, therefore, changes, divided between television sets and domestic living rooms.

However, the spectator’s posture remains passive. Television still constitutes an extremely hierarchical medium, rigidly maintaining the distinction between the audience and the performance. Television sets become attractive representations of the cultural model that television is required to convey, appearing on the screens of every home are stereotypical living rooms within which actors perform edifying scenes of daily life, intended to stimulate the viewer’s mirror neurons to adopt similar behaviors. Television, the ultimate democratic technology, takes on the features of a brainwashing machine.

After the end of World War II, television truly entered every home. In European homes, still scarred by the war’s mortar shells, the glowing box became synonymous with democracy and progress, the two key words through which the new Western geopolitical system based its success. The televisions in Italian, German, or French living rooms, through the architecture of the television set, reproduced foreign life models, specifically stereotypical of the dominant North American thinking. Just as European television sets conformed to the American model, the shapes of homes began to change as well. TV represented the perfect control tool that magically captured the passive spectator, clouding their critical ability. The architecture of entertainment, once a theater and then a home, allowed for a constant and widespread cultural influence on the masses. A demiurgic power never experienced before, made possible by strict control of the airwaves. The ethereal space gained political significance, and national television broadcasting networks began to emerge, state-controlled.

In 1987, an apparently irrelevant event occurred, which, when analyzed retrospectively, marked the beginning of a drastic change. A group of still anonymous individuals managed to replace the television schedule of the WGN-TV broadcaster, a company controlled by the state of Illinois, invading the homes of millions of Americans. They transmitted a brief message with cryptic and self-referential content. They ridiculed some local celebrities while wearing a grotesque mask, a caricature of the fictional TV host/robot Max Headroom. A few moments of pure madness infiltrated the screens of many viewers. The Max Headroom Signal Intrusion is an event that is remembered for its farcical content and the unidentified perpetrators. Signal pirates remained in the shadows. Although part of American popular culture, it is considered a low-value hacking act. Yet, it gave rise to a process of disintegration of the once solid distinction between the audience and the performance. The incident (the term used to describe the event) made it clear that, with some knowledge of physics, control over frequencies could be bypassed, making some form of interaction between the audience and the performance possible for the first time. The low-value mask, the crackling audio, the modified voice, and the DIY set simulating a loss of frequency (probably staged using clumsily manipulated metal sheet) are all elements that tell of a context that was probably domestic, certainly not professional. In other words, this event is a precursor of Gonzo content, a specific category of media products created, performed, and consumed by the same author, content that gives value to the banality of daily life. What we now call Reality, to describe globally successful programs such as Big Brother, derives precisely from this voyeuristic approach to content creation.

Suddenly, the living room expands, and, in addition to the viewer’s armchair, it encompasses the stage, or rather the television set. The domestic space, now completely desecrated, becomes the backdrop of reality and, therefore, simultaneously content and container.

The Max Headroom incident start a sequence of mutations through which the architecture of entertainment has been absorbed into the great black hole of domestic space, a category that has been depleted of meaning as a result of the disappearance of the distinction between public and private. The home and the theater merge with the invention of television and reconfigure as a third space, a hybrid place where content can be both produced and consumed. The acceleration in the development of mass media technologies has had extremely relevant consequences in the form and use of spaces related to entertainment. On one hand, the architecture of entertainment no longer exists, whether we are talking about consumption or the production of entertainment; we cannot say that the production of entertainment has declined. Nowadays, it’s almost redundant to point out that mobile devices for content consumption, such as tablets and smartphones, have replaced architecture, allowing continuous and voracious consumption of entertainment content. The production of entertainment is also accessible to anyone with a smartphone and a profile on any media-sharing platform. Just take a look at the demographics of television and platform viewers to understand that the era of television is coming to an end, and the primary media used for the dissemination of entertainment content will be streaming platforms. Those who produce content for platforms like Twitch or YouTube do so independently, directly from their own bedrooms. Therefore, even the domestic environment changes shape and becomes a “Television Studio,” equipped with cameras and microphones.

For the streamer, the home is both public and private, and except for the bed and the bathroom, it becomes the stage for the tedious and endless spectacle of daily life. As with the theater scene, flattened onto the two-dimensionality of the cinema screen, today, even the home loses its three-dimensionality, reduced to a replaceable background. Nonetheless, the home remains solid in the collective memory as a privileged place for human relationships. The domestic space is often used as a scenographic expedient in which to perform pseudo-artistic routines to share on platforms like TikTok and Instagram. There are even houses designed specifically as sequences of colorful backgrounds, in which celebrities from the platform are contractually required to live to create content industrially. Collab Houses are anti-domestic houses that seem like spatial catalogs of wallpapers and trashy lights and only come alive through the vertical screen of the smartphone. Groups of 6-8 teenagers gather to share intimate spaces forcibly, driven by the possibility of increasing followers and, consequently, income. In these places, neither the touch of the designer nor the emotional stratification due to domestic space consumption is perceived.

Proceeding with hyperboles (a highly efficient exercise if you want to speculate on the future), architecture as a coherent thought about space seems to no longer exist, because the perceptual three-dimensionality of space no longer exists. Thanks to webcams, we can comfortably experience an infinite number of spaces. What we see inside the screen, however, is only a very small portion of these spaces. Screen architecture allows us to observe only fragments, many fragments, but it rarely conveys the complexity of the form in its entirety. Screen architecture, and therefore entertainment, is an accessible and unpretentious place, a space activated and used by anyone. Its fragmentary nature also corresponds to an enormous potential for recombination. It’s not a predetermined space because it lives by accident. The entertainment on the platforms always remains open, ready to be colonized rather than to colonize.

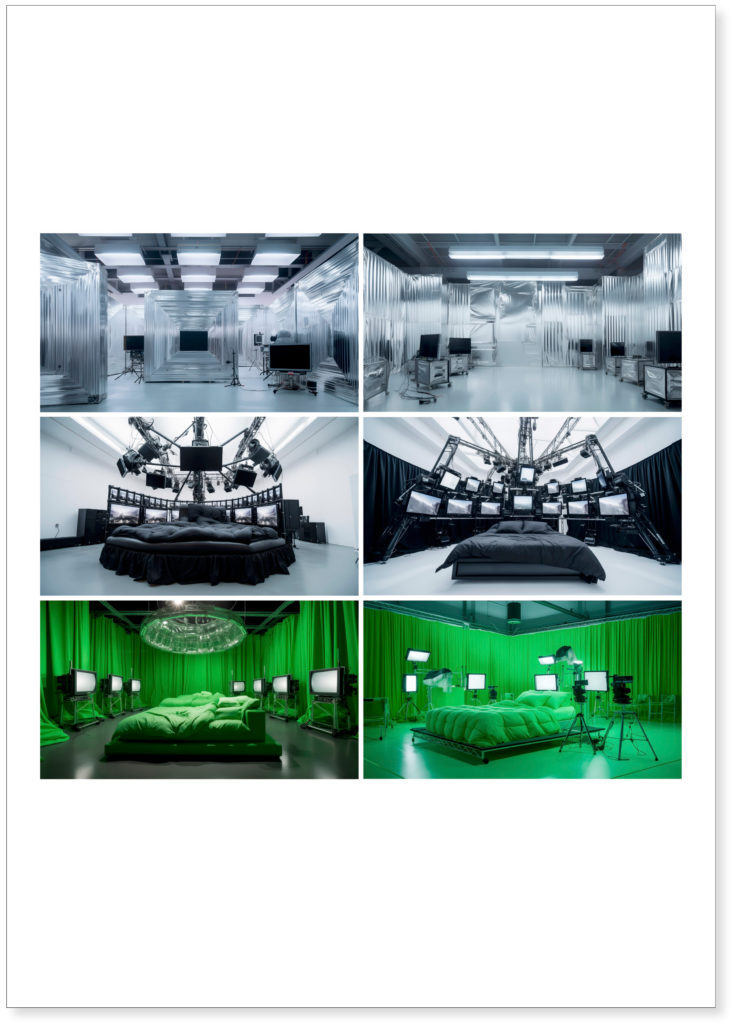

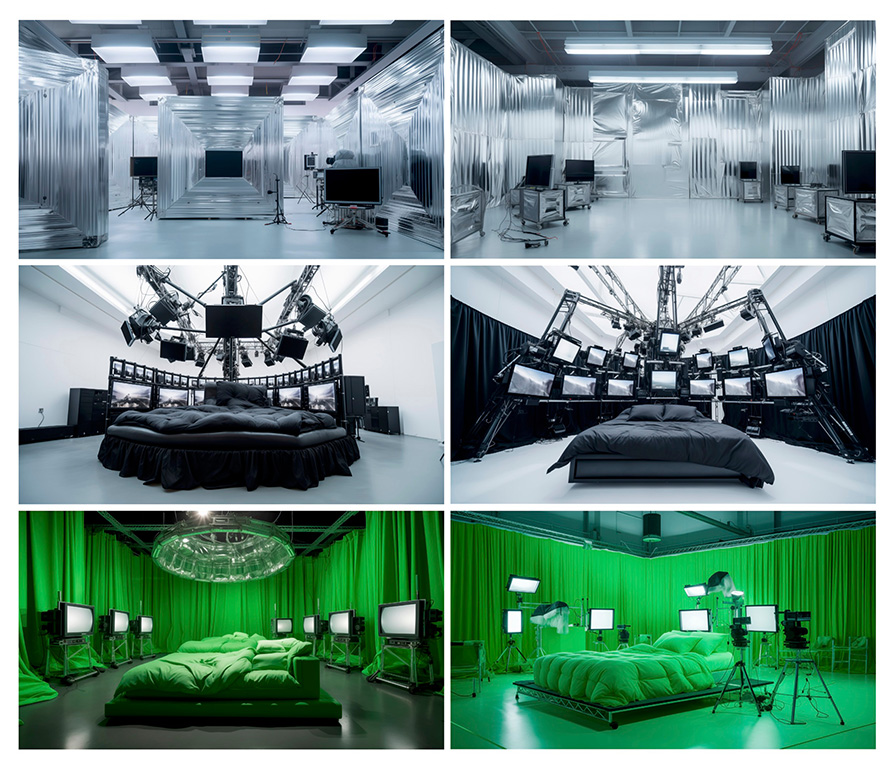

Recreating Max Headroom’s Signal Intrusion Scenography. Prompt 1_a photo of the studio of Max Headroom signal hijackers covered with corrugated metal sheets. 16K, canon eos R5, focal length of the lens is 35mm, –ar 16:9–. Prompt 2_ a photo of a streamer room for the Max Headroom with a photoshooting structure with hanging studio lights and studio monitors, in the middle of a white room. 16K, canon eos R5, focal length of the lens is 35mm, –ar 16:9 –. Prompt 3_ a photo of the secret photo shooting of mysterious hijackers in the 1987, with a green screen structure with hanging studio lights and studio monitors, in the middle of a white room. 16K, canon eos R5, focal length of the lens is 35mm, –ar 16:9 –.