Post Bologna Blues

Pierre Menoud

1. The ratification of the Bologna Agreement on 9th June 1999, produced an unprecedented revolution in the educational system. Part of the greater European project (Euro currency, Schengen, NATO, G8), the declaration was meant to establish a comparable structure for universities throughout the European Union (EU) in order to facilitate the mobility of students across […]

1. The ratification of the Bologna Agreement on 9th June 1999, produced an unprecedented revolution in the educational system. Part of the greater European project (Euro currency, Schengen, NATO, G8), the declaration was meant to establish a comparable structure for universities throughout the European Union (EU) in order to facilitate the mobility of students across Europe and increase competition amongst universities.1 At the core of the proposal, the implantation of a common educational currency would ensure the comparability between all institutions: The European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) was decided to be worth 30 hours of work.2 Furthermore, a common 3-cycle framework was put in place from undergraduate study (180-240 ECTS credits), to the master degree (60- 120 ECTS credits) and the doctoral degree levels (120- 420 ECTS credits).3

Under the premises of equity, the project of homogenisation initiated by the Bologna Declaration acted as a tabula rasa in architectural pedagogy.4 Until then, the discipline favoured a pluridisciplinary approach in an attempt to situate architecture within a broader range of studies, but also to stimulate the subjectivity of the students.5 For example, at the Centre de réalisations expérimentales (CREX) in the architecture school of Geneva, students were taught philosophy, history of the environment, geopolitics and biology alongside “traditional” theories of construction, as well as design within the studios.6

Like in most architecture schools at the time, the teaching of Humanities was a central point in Geneva. To develop a comprehensive critical framework, studios and classes were taught simultaneously in the same room using a large wooden table and a common blackboard. Quasi-informal, the configuration of the work space transcended the academic framework. The methodology and the educational content formed a coherent didactic experience based on humanitarian principles and reciprocity.

Eventually, due to an increased financial pressure caused by their non-compliance with the Bologna Agreement, the school was forced to close in 20077. The radicality of the curriculum was inherently non-achievable within the framework of the Declaration and throughout Europe, most experimental programs were eventually reformed or shut down.

2. In order to understand the implacable success of the Bologna Agreement and the ultimate demise of radical pedagogies around Europe, one has to situate the declaration within its context. As Iryna Kushnir, researcher in Europeanization, Institutions and institutional change highlights, the declaration remains a central point in the creation of the EU, and with it, the expansion of a new form of capitalism.8 Based on the theories of Fred Hayek, neoliberalism fundamentally differs from “pure” capitalism in its transnational reach.9 The EU undermined the autonomy of the signatory nations in order to create a central market and similarly, the Bologna Agreements fulfilled the same objectives with the homogenisation of the curriculum throughout Europe.

The premise of the neoliberal project is as simple as it is effective; everything is now to be treated as a commodity. Thus, knowledge, like wheat, could be bought, traded, or even speculated upon. As Chris Lorenz explains in his paper “Will the universities survive the European Integration?”, the Bologna Agreements implemented the necessary structures to transform the very essence of knowledge production.10 Contrary to the way scientists of the Enlightenment sought knowledge in order to define a “truth”, the Bologna system defines knowledge as a simple currency. Knowledge is now no longer an end itself, but merely a means to extract capital. Through a Marxist perspective, the new curriculum can be understood an unprecedented transition from education for its “use value” to education for its “sign exchange value”, as Jean-François Lyotard argues:

“The old principle that the acquisition of knowledge is indissociable from the training (Bildung) of minds, or even of individuals, is becoming obsolete and will become ever more so. […] Knowledge ceases to be an end in itself, it loses its ‘use-value’”.11

As a paradigm of neoliberalism, competition is central to the proper functioning of universities. The choice of courses, professors, doctoral students and their numbers is directly defined by the market.12 The emergence of complex ranking systems aimed at quantifying an asset’s performance is pushing universities towards a rationalisation of the educational process.13 For example, the “impact factor” is an index used in the academic world to measure the importance of an author or a journal. Independent of its intrinsic quality, its market value is directly determined by its influence calculated in academic citations.14 Thus, knowledge is abstracted to a simple quantifiable performance; “homo academicus is now modelled after homo economicus”.15

Bologna thus rationalises the educational process, but also participates in the standardisation of its content and the ranking of knowledge according to its marketability.16 Furthermore, transferability is essential to the new system which forces the educational content to be “mathematically” quantifiable. Consequently, it favours “explicit” knowledge which can be learned through study and tested through examination rather than tacit or embedded knowledge learned through process and repetition.17 Being able to test students’ explicit knowledge in a subject makes standardisation of courses and grades much easier and, according to Joan Ockman, explains the recent expansion of polytechnics, whose curriculum is mainly based on scientific branches. The marketability of “applied technologies” particularly leads private companies to allocate funds to finance research. However, this also leads to increasing influence by these corporations over the direction of the educational programme. For example, the closure of the CREX in Geneva is directly linked to the introduction of the architecture programme at the Ecole Polytechnique de Lausanne.18 Sponsored by Holcim, Rolex and Logitech, the Lausanne school is infinitely more lucrative than an experimental programme based on environmental philosophy. Moreover, thanks to the allocation of funds in their respective fields, they can also expect a direct return on their investments.19

As argued by Pier Vittorio Aureli, the fundamental shift initiated by the Bologna Declaration is in the fact that the new architectural curriculum favours the formation of a new entrepreneurial class, rather than the “formation of a good citizen”.20 Indeed, without the previous critical framework, students reproduce the same systemic schemes they are taught; an endless loop of oppressive architectural production. Through the concept of the habitus, Pierre Bourdieu defined a system of values and behaviours, both formal and informal, implementing a correlation between the product, the circle of production and reproduction. Thus, the habitus would perform as “structures structurées prédisposées à fonctionner comme des structures structurantes”.21 Hence, when looked upon through a Bourdieusian lens, the globalised study plan reinforces and replicates ideas and practices of the dominant culture: male, white and western.22

As defined by Antonio Gramsci in the 20th century, the homogenisation of educational programs is undoubtedly linked to a hegemonic dynamic aimed at establishing a central power.23 The Bologna Declaration, based on the Anglo-Saxon university system, forced the rest of Europe to comply with its demands, which resulted in the suppression of localised curricula. Furthermore, it prevents through financial incentives the production of an alternative system that does not conform to existing power structures.24 Therefore, as Eva Hartmann argues, the design of the Bologna Agreements can be seen as an unprecedented attempt of cultural colonisation.25

3. The homogenisation of the different curricula has been essential to the functioning of the new school system. However, this has resulted in an inexorable rationalisation of educational content and forms of pedagogy leading to a suppression of potential alternatives. The standardisation of the system is, however, carried out in order to facilitate transferability and exchanges, which, according to the original statement, aims to democratise “access to education, training opportunities and related services” throughout Europe.26 With its noble aim of facilitating intercultural encounters and exchanges through the single structure, the Declaration has in fact only served to propagate the dogma of neoliberalism.27

If the new forms of teaching are articulated around the concept of marketability, the creation of a new academic currency is a key feature of the new curriculum. The ECTS does not represent a monetary value as such, but rather a standardised equivalence between time and performance. Therefore, the European Higher Education Area decided that 1 credit will be worth 30 hours of “successful” work.28 However, the very basis of the equation is problematic; although ECTS credits are supposed to define a common basis on material elements, they relate two abstract values: time and quality.

Architecture, at the intersection of art and technology, is confronted with the impossibility of conforming to the logic of universal credit. The quality of a project, itself debatable according to the subjectivity of the master, does not systematically correspond to its equivalent workload. The possibility of granting – or not – credits thus becomes an additional means of pressure, allowing teaching staff to increase the workload at will. In that sense, ECTS caused the opposite reaction in architecture to the one originally intended; instead of regulating the workload to be done to obtain a certificate of competence, it opens a loophole to increase competition between students and between universities.

“We must in particular look at the objective of increasing the international competitiveness of the European system of higher education. The vitality and efficiency of any civilisation can be measured by the appeal that its culture has for other countries. We need to ensure that the European higher education system acquires a world-wide degree of attraction equal to our extraordinary cultural and scientific traditions.”29

Competition is essential for the proper functioning of neoliberalism. In that sense, the facilitation of transferability induced by the standardisation of the curriculum and the introduction of ECTS credits actively reinforces competition in the academic environment. In order to do so, a maximum of workers – or in that case, students – must be put in competition, and the Bologna Agreements define the creation of a single educational market where universities pit students against each other in order to achieve the best possible results. However, the regularisation of working time promised by the instigation of a universal credit system is inherently incompatible with architectural studies. Therefore, the theoretically “healthy” competition turns into a continuous exploitation where the constant fear of academic failure, used as a repressive tool, prevents students from actively tackling the multiple challenges inherent in their studies.30 Like the factory worker, students have given up on promises of qualitative apprenticeship by accepting their exploitative condition.

Internalised, this culture of violence is justified by numbers, rankings, credits, and grades, regardless of the intrinsic value of the education. Because of the raging competition throughout Europe, the Bologna System reinforces the need to obtain a “proof” of knowledge, as a token of competence. In consequence, experimentation with potential failure is not rewarded, which questions the ability of competition as a factor of progress. Thus, as Ivan Illich already wrote in the introduction of “De-schooling Society”:

“Many students, especially those who are poor, intuitively know what the schools do for them. They school them to confuse process and substance. Once these become blurred, a new logic is assumed: the more treatment there is, the better are the results; or, escalation leads to success. The pupil is thereby “schooled” to confuse teaching with learning, grade advancement with education, a diploma with competence, and fluency with the ability to say something new. His imagination is “schooled” to accept service in place of value.”31

In order to regulate the number of future practitioners, competition is reinforced by the importance given to the grading system, which in theory defines a fair and rational model that rewards workload and quality. However, the Bologna System does not consider the differences or the multiplicity of students. As a consequence of the ever-increasing workload, the System favours those who have some stability and easy access to financial and social resources. In contrast, those who have less time and less money are more likely to suffer financial difficulties, more likely to suffer from mental health issues, more likely to fall behind on school work, and more likely to drop out.32

Architectural studies actively participate in social reproduction, which is already pronounced at the level of higher education.33 Consequently, the hegemonic dynamic is also reproduced in the professional environment where women make up a smaller proportion of working architects, managers, and business owners in most countries, while BIPOC women are almost non-existent in the professional world.34 In the US, black people only make up for 2% of the licensed architects, while accounting for 13% of the wider population, whereas black women represent 0.2% of the licensed architects.35 Even though this dynamic is not exclusive to the architectural discipline, its consequences are particularly relevant in our case with regard to the power of spatial reproduction that architecture carries. Indeed, the lack of diversity – whether in school, or in offices – directly impacts the political production of spaces, and eventually materialises inequalities in the built environment.

4. From its conception to its implementation, the Declaration has been a great success from the European Union’s point of view. 49 countries – including Asian countries, not signatory to the Lisbon Treaty – are currently active members of the project. Never before have so many European universities topped the Shanghai ranking, while European universities witness an unprecedented number of students enrolling per year. Thus, many of the goals of the Bologna project have been achieved. However, as we have seen from the text, the implementation of the new System has also put an end to unconventional educational experiments, as they could not function without the subsidies of a state signatory to the Agreements. Moreover, the implementation of the project has actively participated in a standardisation of educational content and forms of learning, a suppression of diversity, while establishing a culture of violence caused by extreme competition.

Thus, the “real” success of the new curriculum leaves much to be desired. But what other alternatives exist today? How can they be implemented, without subsidies, without time, and in the face of the adversity of the entire system? If one accepts the practical impossibility of creating organisations outside the system, why not fight it from within instead. As David Harvey notes:

“By seeking to trade on values of authenticity, locality, history, culture, collective memories and tradition they open a space for political thought and action within which socialist alternatives can be both devised and pursued. That space deserves intense exploration and cultivation by oppositional movements that embrace cultural producers and cultural production as a key element in their political strategy.” 36

Thus, the system needs to retain a space of resistance, in order to increase its “symbolic value”, and it is precisely in that space, that students need to organise alternatives in order to cultivate collective forms of opposition. Nowadays, a growing number of organisations, collectives and committees have entered this space of contestation; Draglab (EPFL), Parity Group (ETH), Volta (Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio), CLAIMING*SPACE (TU Wien), Gender Board (TU Munich) and many more around the world have recently started to oppose the architectural status quo through an intersectional decolonial/feminist/classist lens. Their purpose is to offer an alternative form of knowledge, through alternative means, aiming to subvert the hegemonic circle of reproduction. Going beyond their respective department, school or country, these groups have managed to create a trans-institutional power which enables them to challenge the might of the Bologna Curriculum. Yet, this labour-intensive process does not grant ECTS credits and is often performed at the expense of the students’ well-being. Thus, oppressed parties are pressured once again, into choosing between the sustenance of collective care or their own.

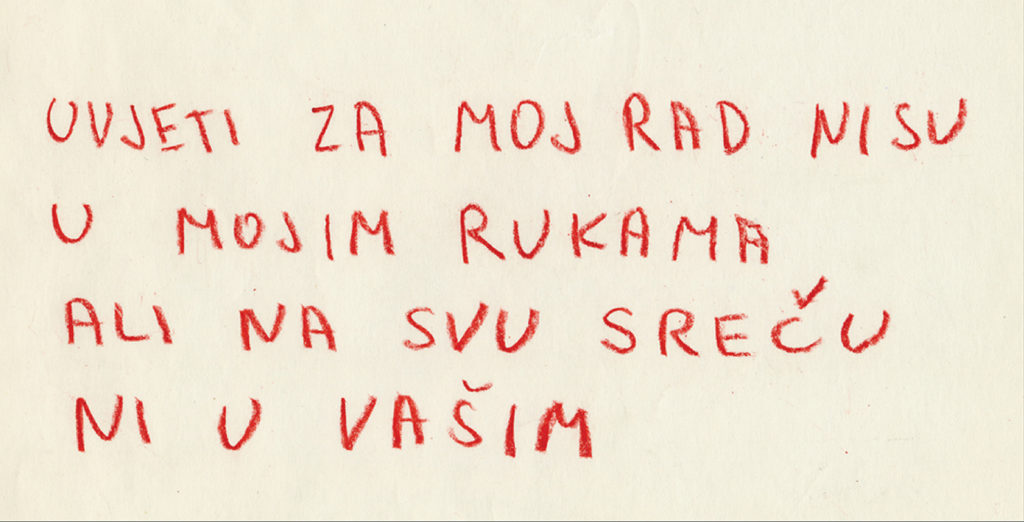

Cover : Mladen Stilinovic, “The conditions for my work are not in my hands but fortunately they are not in yours either”, 1972

1. The European Higher Education Area, “The Bologna Process and the European Higher Education Area,” accessed May 4, 2022,https://education.ec.europa. eu/education-levels/higher-education/higher-education-initiatives/inclusive-and-connected-higher-education/ bologna-process

2. Patrick Atack,“What is the European Credit Transfer System (ECTS)?,” 4th May 2022, accessed May 4, 2022, https:// www.study.eu/article/what-is-the-ects-european-credit-transfer-and-accumulation-system

3. The European Higher Education Area, The Bologna Declaration of 19 June 1999: Joint declaration of the European Ministers of Education, June 19, 1999, http://www. ehea.info/page-ministerial-conference-bologna-1999

4. The discourse of renewal – moments of destruction, allowing moments of creation – is characteristic of the neoliberal dogma. See: Nik Theodore, Jamie Peck, Neil Brenner, “Neoliberal Urbanism: Cities and the Rule of the Markets,” in The New Blackwell Companion in the City. (London: Blackwell Publishers, 2011), 18.

5. Pier Vittorio Aureli and Peter Eisenman, “A Project Is a Lifelong Thing; If You See It, You Will Only See It at the End.” Log, no. 28 (Summer 2013): 68.

6. Vanessa Lacaille and Mounir Ayoub, “The Geneva School (1999-2007)”, OASE, no. 102, (2019): 24.

7. Secrétariat du Grand Conseil. Rapport de la Commission de l’enseignement supérieur chargée d’étudier la pétition pour le soutien de l’Institut d’architecture de l’Université de Genève, 9th June, 2008.

8. Iryna Kushnir, “The Role of the Bologna Process in Defining Europe.” European Educational Research Journal 15, no. 6 (November 2016): 664– 75.

9. Quinn Slobodian, Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (Harvard University Press, 2020)

10. Henry Etzkowitz, “The Evolution of the Entrepreneurial University.” International Journal of Technology and Globalisation vol. 1, no. 1 (September 2004): 64-77. DOI: 10.1504/IJTG.2004.004551

11. Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984),

12. Henry Etzkowitz, “The Evolution of the Entrepreneurial University.” International Journal of Technology and Globalisation vol. 1, no. 1 (September 2004): 64-77. DOI: 10.1504/IJTG.2004.004551

13. Lorenz, Chris, “Will the universities survive the European Integration? Higher Education Policies in the EU and in the Netherlands before and after the Bologna Declaration” Sociologia internationalis 44, no. 4 (March 2016): 123-151.

14. Waltman, Ludo, and Vincent A. Traag. “Use of the journal impact factor for assessing individual articles: Statistically flawed or not?.” F1000Research vol. 9 366. 1 Mar. 2021, doi:10.12688/ f1000research.23418.2

15. Lorenz, Chris. p.123-151

16. Joan Ockman, “Slashed”, accessed May 5, 2022, https:// www.e-flux.com/architecture/history-theory/159236/ slashed/

17. Joan Ockman, “A Brief History of Architectural Research” (Lecture, EPFL, Lausanne, 4th June 2019)

18. Vanessa Lacaille and Mounir Ayoub, “L’école de Genève,” accessed May 5, 2022, https://www.espazium. ch/fr/actualites/lecole-de-geneve

19. Lorenz. p.123-151

20. Pier Vittorio Aureli and Peter Eisenman. p.68

21. Bourdieu, Pierre, Le Sens Pratique (Paris: Les Editions De Minuit, 1980): 82.

22. For example, in a census produced in 2020 at the EPFL by Morgane Hofstetter and Marion Fonjallaz, 335 male architects were discussed throughout the Bachelor whereas only 12 females were mentioned (sometimes as “wife of”, like in the case of Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi)

23. Antonio Gramsci, Quaderni del carcere (Turin: Einaudi, 1975): 2343.

24. James Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998)

25. Eva Hartmann, “Bologna goes global: a new imperialism in the making?” Globalisation, Societies and Education 6, no. 3 (October 2008): 207-220. DOI: 10.1080/14767720802343308

26. The European Higher Education Area, The Bologna Declaration of 19 June 1999: Joint declaration of the European Ministers of Education, June 19, 1999

27. Claudia Wiesner, “Capitalism, democracy, and the European Union”, Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 10, no. 3-4 (December 2016): 219-239. DOI:10.1007/ s12286-016-0320-y

28. Atack

29. The European Higher Education Area, The Bologna Declaration of 19 June 1999: Joint declaration of the European Ministers of Education, June 19, 1999

30. Julie Malfoy, “Suicide en école d’architecture: «On nous poussait à bout psychologiquement et physiquement»”, Libération, May 3, 2022, https://www.liberation. fr/societe/suicide-en-ecole-darchitecture-on-nous-pouss a i t – a – b o u t – p s y c h o l o g i q u e m e n t – e t – p h y s i q u e ment-20220503_LZI4SEVLSVC4ZI6YJYLKLZNBYE/

31. Ivan Illich, Deschooling Society (New York: Harper & Row, 1971): 27.

32. Vivyan Adair, “Poverty and the (Broken) Promise of Higher Education,” Harvard Educational Review 71, no. 2 (July 2001): 217–240. https://doi.org/10.17763/ haer.71.2.k3gx0kx755760x50

33. Gabriel R. Serna, “Social Reproduction and College Access: Current Evidence, Context, and Potential Alternatives.” Critical Questions in Education 8, no. 1, (Winter 2017): 1-16.

34. Laura Mark, “Women in Architecture survey reveals widening gender pay gap,” The Architect’s Journal, February 8, 2017, https://www. architectsjournal.co.uk/news/ women-in-architecture-survey-reveals-widening-gender-pay-gap#:~:text=level%20for%20 women.-,’,pay%20gap%20 increasing%20with%20seniority.

35. Unknown, “On Race and Architecture,” Curbed, February 22, 2017, ht tps : / /ar chi ve. curbed. com/2017/2/22/14677844/architecture-diversity-inclusion-race

36. David Harvey, “The Art of Rent: Globalization, Monopoly and The Commodification of Culture,” Socialist register 38 (March 2002): 93- 110

Pierre Menoud was born in Geneva in 1995. He studied architecture at the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), where he completed his Bachelor’s degree in 2019. He is currently finishing his diploma at the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich (ETHZ) accompanied by Arno Brandlhuber. During his studies, he pursued several internships in Brussels, Zürich and Geneva, where he worked collectively on research, exhibitions and publications. Founding member of the ROHBAU collective, his multi-disciplinary practice deals with the political history of urban forms and the contemporary role of the architect within capitalism. In 2021, he published his first solo article “drills, skills and pills” in L’Atelier Magazine and he recently completed a self-built project at the Stadionbrache of Zürich.