Grotesque Lessons from the Boudoir

Marine de Dardel

Who would be so besotted as to die without having made at least the round of this, his prison? Marguerite Yourcenar, The Abyss (1968) Libertine Philosopher The choice of D.A.F de Sade1 to enlighten us on current states and future becomings of ‘Learning Architecture’ might seem somewhat unexpected; yet the provocation is not vain, nor the seductive operation […]

Who would be so besotted as to die without having made at least the round of this, his prison?

Marguerite Yourcenar, The Abyss (1968)

Libertine Philosopher

The choice of D.A.F de Sade1 to enlighten us on current states and future becomings of ‘Learning Architecture’ might seem somewhat unexpected; yet the provocation is not vain, nor the seductive operation bluntly spiteful. Rather, it implies an apparently naive but fervent exhortation to reconsider the man, beyond expeditious reception reducing him to sensuous profligacy, in order to reflect upon the role and quality of the Institution as the main vector of (social) order, political revolution, formation of knowledge, elaboration of critical thought and aesthetic sensibility.

Considering how satirical critics such as Louÿs and de Sade, appropriating the tradition of initiation novels, deflected their allegorical value as pedagogical instruments in order to mask poetic or revolutionary intent within educational treatise; an oblique lecture of Sade’s La Philosophie dans le Boudoir2 suggests a different perspective on education and political action. The theatricality of the spatial setting, the discursive structure of the dramatic dialogue, the philosophical pamphlet Frenchmen, yet another effort, if you would become Republicans (fifth dialogue) suggest serious leads of what ought to be hoped for within the realm of architecture.

The inevitable controversy sparked by the marquis’ fulfilled or fantasied cruelties, sexual obscenities and blasphemy, more often than not, renders the broad scope of this work opaque: I do not blame those who dare not to leap into the abyss of thought he opened up, I merely wish to bring to light how strategies may be derived from de Sade’s liberal stances in order to question the status quo, to mistrust conventions, and face the existential anguish awoken by vertiginous freedom (of choice and action). Moreover, despite a continuous oscillation between condemnation and glorification, rejection and praise, the causes of the lasting fascination exercised by de Sade and his apathetic libertines must be found somewhere in this indeterminate region between monstrosity and banality.

His preoccupation with the structures of social relations and the analysis of power make him an intensely political writer, deliberately setting out to write against the cultural norms and structures of thought constituting the world. The repetitiousness of his vehement refutations of the existence of God reveals the shift from logical to metaphysical revolt: Sade’s atheistic revolt is an existential one (God is the most revolting lack of being); not unlike the artistic revolt before the irreconcilable conflict between form and content (where ‘blank’ space might be the most intolerable lack of meaning).

Naturalistic Venture3

Subsequently to this atheistic revolt, Sade replaces the transcendent God and the supremacy of Reason by prioritising Nature: of the infinite ambivalence of the natural world, of it’s vivifying principles of brutality and violence, he derives the features upon which to build his account of the universe. Nature stoically creates and obliterates, with little concern for the fate and form of any mound of flesh, as the annihilation of moulded creatures implies the chance to recast them anew. Sade emphasises the continuity of humans and other animals. His libertines strive to equate Nature through a process of estrangement and, paradoxically, of disembodiment: personal preferences and any kind of self-interest, preoccupations for the consequences of their deeds, empathy for victims’ sufferings are radically eliminated. Sade’s apathetic characters aim at something beyond any particular expression of cruelty; they aspire to an activity that can persist unhindered and unobstructed.4 A mechanical dehumanisation, a metaphorical decapitation, a metaphysical pursuit, in order to stoically engage with the universe and live in accordance with Nature.

Ingenuous Poetry

Sade referred to himself as a philosopher describing life as endless flux and destruction and, holding that total harmony would destroy the natural order, asserted the moral attitude of the revolutionary. Indeed, “[he] never stopped expropriating man from within himself and giving him back to the world”5 without realising this was the gift of all great poets, the great privilege of childhood to reconquer one’s sense of physical sovereignty. Breton already pointed out to Sade’s ‘innocent ferocity’ of childhood in his Anthology of Black Humour; Le Brun’s surrealist lineage is accredited for a profoundly poetic approach to the marquis, and a vigorous opposition to any kind of doctrine: “it is in the nature of ideologies to produce ideas without bodies, ideas that only develop at the expense of the body; […] – poetry speaks of nothing else.”6

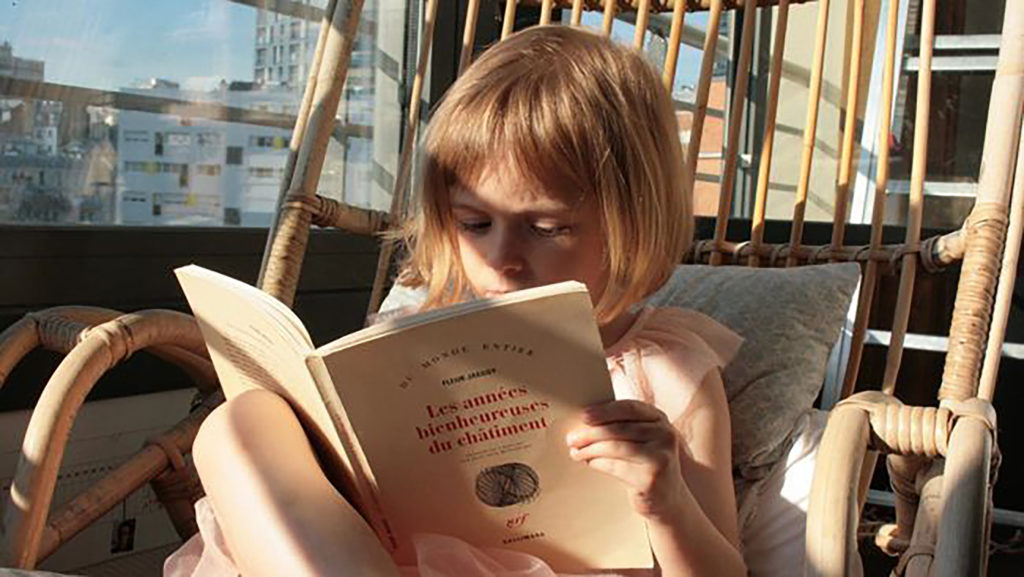

“this was the gift of all great poets, the great privilege of childhood to reconquer one’s sense of physical sovereignty.” [Eric Rondepierre ‘Confidential Report’, Lectrice 2 (Jaeggy) Photogramme (Galerie le bleu du ciel)]

The discourse of Sade’s libertines is invariably built according to the method of paradoxical praise: demonstrations sustained by the strength and amount of converging examples in order to prove that the norm interiorised by the individual, and deemed by him as universal, is but a prejudice contradicted by other practices. No fact could be moral or immoral in itself as there are no facts at all, merely interpretations. Such moral and philosophical relativism strips all signifiers bare of their meaning. The terms ‘vice’ and ‘virtue’ are no longer the two categories of an immutable moral typology, they solely categorise in a contingent manner a reality that is neutral in itself. Through the eyes of his characters, he describes the hallucinatory spectacle of a uniform reality – consisting of crimes and debaucheries endlessly repeated – not unlike the sanguinary displays he witnessed from the depth of his prison. Countless executions and the bloodcurdling strike of the guillotine, the nauseating sameness of years spent in isolation, the maddening solitude of prison – were submitted to the same harrowing law of endless repetition. Against the backdrop of the revolution, the crimes he describes become tainted with a bitter irony. He strives to condemn historical progressivism interspersed by the successive overrun of previous flaws, where we are but powerless pawns facing the absurd repetition of the same crimes and witnessing the nonsensical stuttering of History. Sade foreshadows Nietzsche in many regards; he too, philosophises with a hammer, as every case he exhibits tremors of the doxa of his time.

Theatrical Body8

It was during his imprisonment in the 1780s that Sade wrote the greater part of his theatre, unfolding his singular atheism and bringing his interdependence of mind and body into play. Unlike other philosophers of this time, he goes further than to set the sovereignty of his mind against the illusion of a divinity. For Sade, this sovereignty is established by the reality of the body alone, which is why the theatre, insofar as it functions as the site of bodily incarnation, will offer him the best means of taking free thinking beyond the limits of philosophy. Sade’s novels brought philosophy onto the stage, he made it physically present through a veritable theatricalisation of thought which begins by asserting itself as much as a critique of theatre by philosophy as of philosophy by theatre. He thus introduced the body into the philosophical debate. Just as he had himself been educated by the Jesuits who saw theatre as a pedagogical instrument of first order, he went on exploiting the dramatic space of the stage to unravel his acid critique of modernity and hopefully educate his contemporaries.

Satirical Carnival

Throughout Sade’s libertine works, there is evidence of a carnivalesque spirit which Mikhail Bakhtin9 identified as a ‘rehabilitation of the flesh’ characteristic of the Renaissance in reaction against the ascetic Middle Ages, but which he declared virtually absent from the desperately ‘abstract’ Enlightenment. A consequence of Sade’s focus on the body is the implication of the carnivalesque which also has a politically subversive impact: inversion of all official hierarchies accompanied by what Bakhtin called ‘grotesque realism’: “The essential principle is degradation, that is, the lowering of all that is high, spiritual, ideal, abstract; it is a transfer to the material level, to the sphere of earth and body in their indissoluble unity.”10 In the Philosophie dans le Boudoir, the reversed focus of philosophical thinking from the mind to the body is accompanied by a savage black comedy that indeed corresponds closely to Bakhtin’s ‘grotesque realism’ as a positive political force. The entire dialogue can be read on a political level as inverting all hierarchies in ironic echo of the Revolution.11 The Boudoir is truly carnivalesque insofar as it operates the inversion of the low and the high, the official and the popular, the grotesque and the classical. Depicting the body as ‘multiple, bulging, over- and undersized, protuberant and incomplete,’ ambivalent fragments longing for hybridising to achieve the illusion of determinacy.

Transparent Institutions

The political and educational quality of Sade’s pamphlets tend to be overshadowed by the common condemnation of deviant figures, censoring outcasts declared unfit for a righteous society. The marquis was prey to conflicting notions on society, government and class structure. He was obsessed with the dissection of the structures and nature of power, with indeed a certain pedagogical quality: how might the revolution be communicated? There is also the recurring theme of transparency: immediacy, publicity, radiant virtue, freedom from plots. Transparency is both the key and the trap – not only the solution sought through pedagogy but also the presupposed state of things hence obviating the need for pedagogy.12 This paradox corrupts the hierarchies and systems inherent to the Institution. Under these circumstances, is the refusal of Sadism still a necessary posture?

Grotesque Scenery

If all the world is a stage, our cities – and hence architecture schools where discourse emerges – certainly seem to have become the parodic backdrop to a nonsensical play, a cacophonous comic scenery13: disjointed positions, fragmented visions, erratic laments and foolish scansions desperately seeking for attention. Layered screens and plots, commissions and partitions, multiplied in the name of transparency – rendering the space of debate all too opaque after all. Time has come to reclaim the central political void and, borrowing from Sade, to overlay tragic and satiric sceneries before ultimately placing the body in the centre of the stage. The contemporary set (of both the city and the place it is thought and taught) would extend towards infinity (unobstructed vanishing point); humility should prevail (no frontal views); indefinite lines, shifting shapes and dynamic forces (suggested by the rustling satirical landscape) could embrace change, tropisms and tensions: the rise of a truly grotesque scenery where philosophical doubt, positive political forces, poetry and lyricism converge. Sadistic Endeavour14 Delacroix, Baudelaire and Wagner: a trinity of artists bent on dominating other minds by sensuous means. The beholder has no hope to resist the forces playing him like an instrument. Now consider Michelangelo’s Sforza Chapel (1561-64), Shinohara’s Tanikawa House (1972) or Takamatsu’s Ark (1983) – was it not also their ambition “to reach and as it were possess […] that tender and hidden region of the soul by which it can be held and controlled entire […] to enslave… and to bring us into bondage”15? The architect is at once scientist, composer, poet, actor, mechanic, fetishist, zookeeper: he must acquire adequate knowledge of psychology, physiology and probability; affecting others treated at once as selves, machines, animals. As a discipline, architecture is undisputedly a matter of force, every building is an action, any space a choreography. It must ultimately provoke, and thereby train to provoke, an erection of both the mind and the soul.16

Learning Architecture

Sade’s satirical criticism and revolutionary exhortations exemplified by the dialogues staged in the Boudoir expose:

1) stoic disembodiment and estrangement, to equate Nature’s creative and destructive processes;

2) poetic displacement and lyrical disruption, to reclaim childlike ingenuity;

3) paradoxical praise, to question norms and conventions;

4) the theatrical stage of bodily incarnation, to transgress the limits of philosophy;

5) carnivalesque distortion, satirical criticism and grotesque realism as positive tools of political thought, to overthrow status quo;

6) dissection of organs and structures of power, to fathom their literal and phenomenal transparency;

However unsettling, the Marquis’ libertine philosophy inspires us to repress the generalised tendency towards demagogy. It instigates us to reclaim the institutional environment as a political space of discourse, of experimentation of ethos, pathos and oikos – striving for the radical discredit of the norm. Of course, daring to interfere with the majority and its established prejudices demands moral integrity, courage of convictions and fearless insolence. And if it implies assault and outrage, so be it. Ultimately, an Institution must train from individuality towards collective excess, rather than lead collective exhaust of individuality towards extinction. It must assume the trying role of the framework beyond which will be worked. Remembering that every inclusive attitude is by default an exclusionary position, it must not bow to the whims of the majority, of the average, yielding under the levelling forces of normalisation. It must provoke frantic creative impulses, teach all forms of pictorial violence17 and instruct how to end up like an animal, completely numbed through intoxication, since otherwise we would be afraid of faltering. Learning to dare, to risk, to fail. Could any less be expected from those who shape the space of bodily experience? From those who wish to build timeless stages reflecting cosmic orders and who claim to have probed the depths of aesthetic thought? To all aspiring architects intending to contribute to the tragedy of matter seeking its form, striving for an authentic absolute and radical aesthetics and discourse, Sade just might have something unique to teach after all. Dimmest possibilities of something else, both fantastical and dreadful, that may still succeed. Grafting the prophetic eye of the philosopher18 to the boundless mind of the sadist, I urge the institution to train “violent” minds, whose ambitions turn away from ideology, conformism and prejudice.

Let us assume the cloak of the lover, the lens of the poet, and walk with the mad.

“Dimmest possibilities of something else, both fantastical and dreadful, that may still succeed.” [Eric Rondepierre, ‘Excédents’, La Vie est Belle (1993)]