Architecture and its educational turn

Sabine Bitter and Helmut Weber

The course I (Sabine) enjoyed most at Simon Fraser University (SFU) near Vancouver, BC, was our first-year public art project that placed student artworks all over the campus. Although I was fascinated by the spatial and architectural qualities of the iconic buildings up on Burnaby Mountain, I soon realized that my enthusiasm for the modernist […]

The course I (Sabine) enjoyed most at Simon Fraser University (SFU) near Vancouver, BC, was our first-year public art project that placed student artworks all over the campus. Although I was fascinated by the spatial and architectural qualities of the iconic buildings up on Burnaby Mountain, I soon realized that my enthusiasm for the modernist campus was not universally shared. The campus, built in 1965 by Canadian architects Arthur Erickson and Geoffrey Massey, is a brutalist megastructure which reflects a moment of educational expansion in Canada. Erickson went so far as to claim this new positioning of education and knowledge production would be led by architecture: “Universities are the new visual and intellectual environments.” However, most of the students as well as many of my colleagues experienced the concrete shapes and spaces of brutalist architecture as an outdated, hostile, or even depressive framework for learning and teaching. Despite the positive and enthusiastic re-evaluation of brutalism globally, I have not seen this perspective of the architecture and program of the campus change. The new buildings on the campus largely ignore Erickson’s original masterplan and the recent renovations and maintenance treat the beauty of the concrete as a problem to overcome. This had led to demolitions of several key buildings on campus. I have followed the development of the campus and I always wondered why there was not more debate about the qualities and values of this architecture.

To get at this perception of Erickson’s architecture, and to critically examine how the public architecture of the 1960s and 1970s hold and create social meaning, we turned to two exemplary educational megastructures from Erickson – SFU and University of Lethbridge, Alberta. Our projects Public Seminar1 and Unsettler Space2 try to identify what we call “past future moments” in which universities are imagined as sites of both speculation on and critique of the university’s present and future role. We look at historical experimental spaces of learning as markers of an educational turn in architecture which anticipated and still informs the current conditions of flexibility and mingling of learning, working and living within cognitive capitalism and its new forms of immaterial labor.

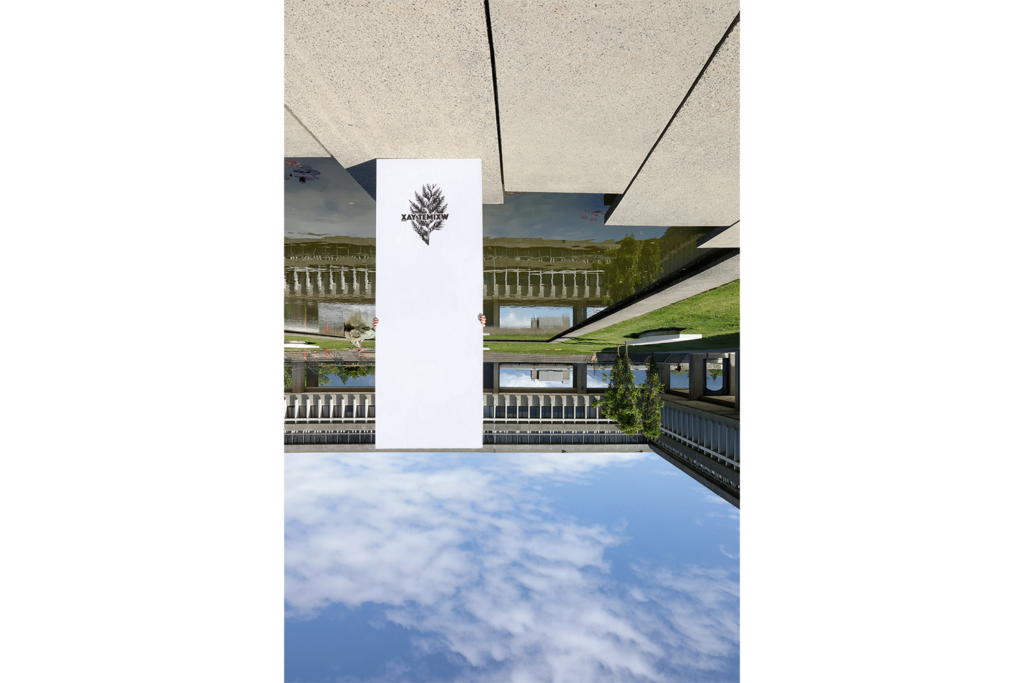

Unsettler Space: xaitemixw (respect in Skwxwú7mesh), 2020

For Public Seminar we focus on the radical architectural and pedagogical concepts that shaped the iconic architecture of the University of Lethbridge, also from Erickson, built in 1968 to 1971. For Erickson, this campus was a next step in rethinking the educational institutions themselves. In “The University: The New Visual Environment”, Erickson argued “The metamorphosis of the contemporary university has to do with profound and important changes that are challenging the values and the structure of North American society in every aspect. […] The change we see – the dramatic change in the visual environment- of some of the new universities – is not so much a change in architectural thinking, style, structure or technique, but a change in the purpose of the university itself.”3 Regarding the future of the university he postulates: “At the same time that the university is becoming more part of the public domain, it is also engaged more critically in the life of the community. We may find in the not too distant future that the last boundaries of fragmentation are broken down – that the university cannot be separated and isolated, as has most often been the case, from the fabric of the city; nor can university training be separate from everyday existence.”4

The video project “Public Seminar” focuses on how this new understanding of educational institutions and pedagogical concepts were realized spatially, how this mixing of teaching, learning and living was manifested in the architectural and spatial design. Along with its relationship to a spectacular landscape, the university was also unique in its spatial organization. Erickson’s plan combined all aspects of the university in one building, from classrooms, faculty offices and student housing. The long concourse hallway serves as the main axis that runs the length of the building and is bordered with tiered areas designed to function as open classrooms and lounging areas, an influence Erickson took from the Al Azhar University and Mosque in Cairo.

Based on photographs from the University’s archive, of a short-lived experiment of “Public Seminars”, we re-staged a similar seminar in its original location in the long hallway. We worked with a group of students and used a range of archival material in order to raise questions regarding the spatial plan of the university, pedagogical practices today, and the relationship of knowledge and labor. We collectively asked how these progressive pedagogies of the 1960s and 1970s relate to the pedagogical concepts and imperatives of the present, or, how does learning produce particular spaces and spatial relations? Reading excerpts of Erickson’s text on the new visual and intellectual environment, watching promotional videos for the university from the 1970s to the late 1980s on handheld devices and laptops (the very devices that now force a merging of life and learning) as well as a series of signs demonstrating the current student´s condition of learning and studying were all structural elements of the seminar. Students pointed out that Erickson’s radical impulse of blending life and learning has returned as the imperative of life-long learning: “Lifelong learning = always working.” The late-sixties dream of collapsing boundaries to fold learning into life and to coordinate work and life has led to the educational industry of life-long learning.

While Public Seminar reactivates and performs an educational turn in architecture-history, Unsettler Space points towards the necessity of a dramatic epistemological turn and a rethinking of spaces of radical pedagogies today; this necessity is driven by the fundamental challenges that Indigenous knowledges brings to all educational institutions in Canada. SFU, like the University of Lethbridge, was constructed as a “peoples’ university” representing democratization and access to education with the goal of bringing the social peripheries to educational centers for training and progress; yet this national project never really imagined Indigenous students, let alone Indigenous knowledges, being in the university. SFU carries a reputation as a “radical campus,” a term coined due to the actions of students and professors in the mid-1960s in relation to education and labor and because of Erickson’s vision to break down the hierarchies and disciplinary boundaries of education through smaller classrooms and cross-faculty learning spaces – but this radicality really only pointed to reforms within a western model of education and knowledge.

To counter this modernist vision of progress and nationhood that actively excluded Indigenous peoples, Unsettler Space – a project we initiated with Métis scholar June Scudeler – sought to both question the potential of these radical spatial concepts and to enact a form of Indigenous pedagogy on the campus.

This last goal was delayed due to the quick shift to remote learning due to covid. However, in March of 2022 we held a day-long event in the outdoor Convocation Mall at which we, along with Indigenous and other students, silk screened t-shirts that expressed support for Indigenous land struggles and opposed the continuation of an extractive economy that strips resources from Indigenous lands. This event was a platform for dialogue and solidarity. We also produced t-shirts that identified the Squamish language name of the site that the university sits on – Lhuḵw’lhuḵw’áyten (where the bark gets peeled in spring) – in a gesture of decolonizing the naming of the place name. Likewise, Treena Chambers, a Métis writer and students who worked with us, devised a strong linguistic inversion to parody Canada’s process of “reconciliation” with Indigenous peoples – the state’s upbeat term was overturned to now be “Wreckonciliation.” This new term accurately names Adam Gaudry and Danielle Lorenz’s critique on how Canadian universities perceive reconciliation and Indigenization and how Indigenous people ask for transformation: “While universities utilized reconciliation rhetoric in most cases to beef up inclusion policies, Indigenous faculty members envision a transformative indigenization program rooted in decolonial approaches to teaching, research, and administration.”5

Throughout the process of staging such an action on campus, we tried to stick to the protocols we had collaboratively made (under the name “Guests & Hosts”6) to guide our working together that was based on mutual respect, patience, humor and understanding. Did such an action overcome the architectural determinations of the campus and open a new space for Indigenous knowledge? In retrospect, it is not only the built physical spaces of the campus that are determinations (space always matters!), but the hierarchical administrative and functional aspects of the university which underpin its colonial functions. In the accompanying publication to Unsettler Space, Unsettling Educational Modernism, we turned images of SFU upside down, signaling both crisis and enacting a humorous critique. In this way, Unsettler Space makes a playful step towards doing the necessary homework and unlearning that Sami scholar Rauna Kuokkanen requests in Reshaping the University. Calls for scrutinizing historical circumstances and articulating one’s own participation in structures that have fostered various forms of silencing, discrimination and epistemic ignorance represent to Kuokkanen a shift away from the idea of fieldwork toward the idea of homework. This offers a critical way of learning from architecture.

Left: Guests & Hosts, Rights, Justice, Solidarity with Wet’suwet’en, col. photograph, 180 x 120 cm, 2020. Right: Guests & Hosts, Unsettler Space #5, b&w photograph, 45×30 cm, 2020

Likewise, with Public Seminar in Lethbridge, we found that the collapse of life and work and of learning and living is viewed by students now as a fact of everyday life and is therefore relatively transparent. But, if this has been achieved, the question of if incorporating life and learning together has generated any radicality or if has helped expand the conditions of work into every aspect of everyday life: as the students observed, “Lifelong learning = always working,” and this is a long way away from the concept of a fuller life that was a part of Erickson’s understanding of universities.

Dealing with the hopes and plans of a social and cultural modernism rooted in colonial domination illustrates that the modernist educational architecture requires a particular type of engagement and critique. Unsettler Space does not take architecture as a given nor as a stable container, where we are invited to help ourselves to learn as we wish, but to understand architecture as an act. As Eyal Weizman puts it, architecture is social forces slowed down into form, through which we enter into a field of multiple relations. Rethinking educational architecture and entering into ethical relations to reform it comes with a duty; we have to position ourselves in relation to its history and the social forces that produced it in order to reform its potential and build new relations.

Sabine Bitter, University of Lethbridge, 2017