Letter to Students

Shen He and Juan Barcia Mas

Dear classmates, dear architecture students, Some of you might have witnessed the lecture “Unwording: An Aesthetics of Collapse” at gta exhibitions given by Jack Halberstam a few days ago. For some of us, the message he brought to the school was exciting and full of hope. As some students pointed out in the round of […]

Dear classmates, dear architecture students,

Some of you might have witnessed the lecture “Unwording: An Aesthetics of Collapse” at gta exhibitions given by Jack Halberstam a few days ago. For some of us, the message he brought to the school was exciting and full of hope. As some students pointed out in the round of questions, Jack’s proposal “of tearing ‘this shit down’” is extremely controversial within the context of a school of architecture, which is primarily dedicated to the task of erecting structures. Instead, Halberstam proposes an aesthetics of collapse, that visually enacts his vision of tearing down and subverting current hegemonic systems of colonial supremacism.1

It is 1:41 am now. We are finishing this letter last minute (as always) addressed to you, driven by an increasing feeling of discomfort and unease within our academic environment. We would like to open the debate in search for a new way of studying and learning together.

In the 1968 issue of Architectural Design “What about Learning”, Cedric Price defined education at his time as a practice that distorts the mental and behavioural structures of individuals, so as to insert them into predefined social and economic schemes.2 The education system fails to renew itself and reflect beyond its strictures, presumably due to the fact that the formats and contents are solely prescribed by the few. The time of the publication coincided with the student revolts of the Unité Pédagogique No. 6 in Paris, which positioned themselves against the “Beaux-Arts” methodologies that were still put into practice.3 The students accused the faculty of being unable to establish relationships between architectural design and urgent social and political issues.

In 2013, the same question was rephrased by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney in their groundbreaking essay “The University and the Undercommons”, in which they problematized the idea of university in relation to its commitment to professionalisation. The subversive intellectuals who are able to vandalise the norms are necessary to the university, but not welcomed by it: “Maroon communities of composition teachers, mentorless graduate students, adjunct Marxist historians, out or queer management professors, state college ethnic studies departments, closed-down film programs, visa-expired Yemeni student newspaper editors, historically black college sociologists, and feminist engineers” are forced to escape and go underground, because the university “will say they are unprofessional.”4

Since then, few things have changed.

The overall pedagogic structure in the schools of architecture is still organised around a rigid hierarchical structure. Architectural design is taught by recognized architects, in the format of a studio where fierce competition among students is encouraged. These design studios have become capsules in which reproductive design methodologies are taught and, in many cases, fail at empowering students with real autonomy and responsibility. The only possible choice is either to submit and become malleable, with the promise of a secure working position or the possibility of entering an endogamic relationship with university. As Derrida stated, faculties become onto- and auto-encyclopaedic – they reproduce themselves and secure their spread and durability, as well as their supremacy.5 Even the critical academics, as Harney and Moten identify them, will do little harm to the institution itself and will never recognise “the unregulated, ignorant, unprofessional labor that goes on not opposite them but within them.”6 With such a structure, it is almost an impossible task for the academy to adopt radical changes in teaching and to address urgent issues promptly. As a result, the teaching curriculum is still dominated by an all white, male, colonial, extractive and anglo-eurocentric vision of the world. How can we subvert it?

Disciplinarity

In “Discipline and Punish”, Michel Foucault asserts the task of the university, in accordance with that of prisons, is to “straighten out” and correct what he calls “the perverted individual”.7 The correct training deploys hierarchical observation, normalisation of judgement and examination, and is put into administrative and pedagogical use in the modern society. 8 Prison and school are the two sides of a governmental apparatus that operates upon the individual. “Correction begins with the ascription of the body itself, the imposition of body onto flesh; the attribution of perversion to the specific body, which justifies its correction, […]” The discipline that is put into practice in order to correct the perverted individual did nothing but to confirm the perversion, which again called for more instruction.9

To become ‘undisciplined’, to free ourselves from the aforementioned strictures, we have to leave the well-lit territory dominated by disciplinary thinking, and seek for new sites of knowledge.

Postcolonial Theory

As Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi argues in her text “The University and the Camp”, the university, both in its physical form as the campus and its epistemological form as the curriculum, is not innocent to coloniality. The term coloniality “refers to long-standing patterns of power that emerged as a result of colonialism, but that define culture, labour, intersubjectivity relations, and knowledge production well beyond the strict limits of colonial administrations.” Coloniality outlasts colonialism and is therefore still present in Western epistemologies.10

In March 2015, Chumani Maxwele (a student of political science on a scholarship at the University of Cape Town) set fire to the “Decolonise the Curriculum” movement, hurling a bucket of excrement onto a bronze statue of the British colonialist Cecil John Rhodes on the university campus. This incident was followed by a large group of students subversively reshaping the campus: “tagging the statue with graffiti, covering it in black garbage bags, and singing anti-apartheid songs”. The statue was then removed and a curriculum revision in several programs took place with inputs from the student’s union, including the “expansion of the curriculum, greater diversity and inclusion in enrollment and hiring, and the cessation of economic exploitation of campus workers”.11

“Their vandalism produced a forum.” writes Siddiqi.12

Indeed, Rhodes’s legacy was interrogated, which includes not only his financial bequests, but also the worldview he wrote down in his will: to extend the British rule throughout the world, to colonise the entire Continents of Africa and South America, as well as the Islands of the Pacific and the seaboard of China and Japan.13

We must look for the traces such a vision has left in Western epistemologies, and how architectural pedagogy has become one of its political agents.

Maxwele’s “vandalistic” act established a powerful precedent. Postcolonial power structures were interrogated through a performative and vandalistic act that challenged the university in its spatial expression. It has unfolded three key points which might help us imagine different ways of studying architecture.

Challenge the curriculum through spatial intervention in the campus.

The ephemeral studying experience takes place in the campus space, and it is the spatiality of the campus that enables, organises and structures it. Lecture halls, studio spaces and libraries are necessary devices through which a legitimate curriculum is defined and established, however, learning is something that takes place as well beyond the boundaries of the lecture hall . If the curriculum can be thought through the campus space, we might start destabilising it by speculating on the capability of our bodies to transform campus space from an institutionalised one into a fugitive one – through our movements and actions. Those can be performed collectively, and thereby a space can be carved out for a (secret) counter community to develop, that aims at destabilising the foundations of Western academicism in its embodied format – the campus. In this collective bodily experience, the building of community takes place through the emergence of difference, since “difference is not a manifestation of an unresolvable estrangement, but the expression of an elementary entanglement”.14

Establish a counter curriculum through conversations and actions with our peers.

Maxwele’s action opened up a space of critique and debate that questioned the given postcolonial power structures. In fact, his protest revealed that behind the elegant facades of the university buildings, many Black students were already very angry and ready to speak up.

The forum that students established on the following days formed a kind of counter curriculum, filling the gap of (but also questioned) the institution’s predefined curriculum. Just as Siddiqi concludes in her text, “decolonial thinking means that producing knowledge and living it are not separate… It illuminates the links between knowledge, social practices and social action – between architecture, architectural history, and spatial practice”.15

Moten and Harney define “study” as a social event that is never constrained to university.16 In fact, study has been constantly excluded from university – in the name of teaching, and for the sake of making professionals. But as soon as we start to treat all these conversations as study, we start to expand the curriculum across the whole community, through horizontal structures and bottom-up initiatives. Eventually, those peer-to-peer conversations and actions can enact other ways of studying. In the chats after the crit, during lunch time, during a night out, or on the bus of a school excursion, what is discussed “can be discarded, forgotten, but there’s something that goes on beyond the conversations which turns out to be the actual project.”17 We will begin to acknowledge the informal, the rebellious and the counter curriculum as part of the broader meaning of curriculum in formal education.

Let vandalism be our code of conduct.

Maxwele’s scatological act was a vandalistic one. It could have endangered his own position as a student and scholarship holder at the University of Cape Town. The setting up of a counter curriculum will necessarily “break up” with established normativities, codes of conduct, which might jeopardise the positive assessment of the student’s academic performance. We should be ready to fail the exam. Or, as Walter D. Mignolo states, “if you apply to get grants or fellowships to engage in decolonial praxis, be sure that you will not get them.” 18 Let us recall Halberstam arguing for rupture and collapse in a non-reparative way.19 When we break something, the result is at first unexpected – yet the new composition and relationships of the broken elements bring up new significations that were not imaginable before. The act of breaking requires courage, because it comes with a price and it brings no promise for outcome. Still, unbuilding can become a more generative process than building.

The Internal Outside

We are looking for a vision of the outside of the institution, given that the system will not revise itself. But what if this “outside” we are searching for is, as a matter of fact, an “internal outside”? The refugee camps, the indigenous resguardos, the hidden cruising spots – the sites that are already among us. Through the terms of Moten and Harney, we want to go beyond “general antagonism”20, and start to imagine what can happen informally. If “nowhere” is somewhere we take refuge from the institution, then we are all already in the refuge.

Let’s take our school.

Looking forward to hearing from you,

Shen He and Juan Barcia Mas

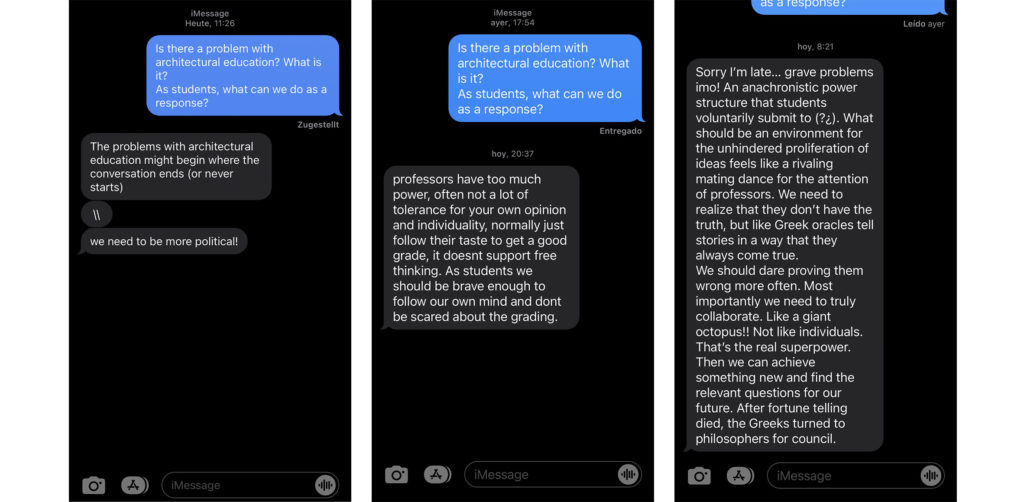

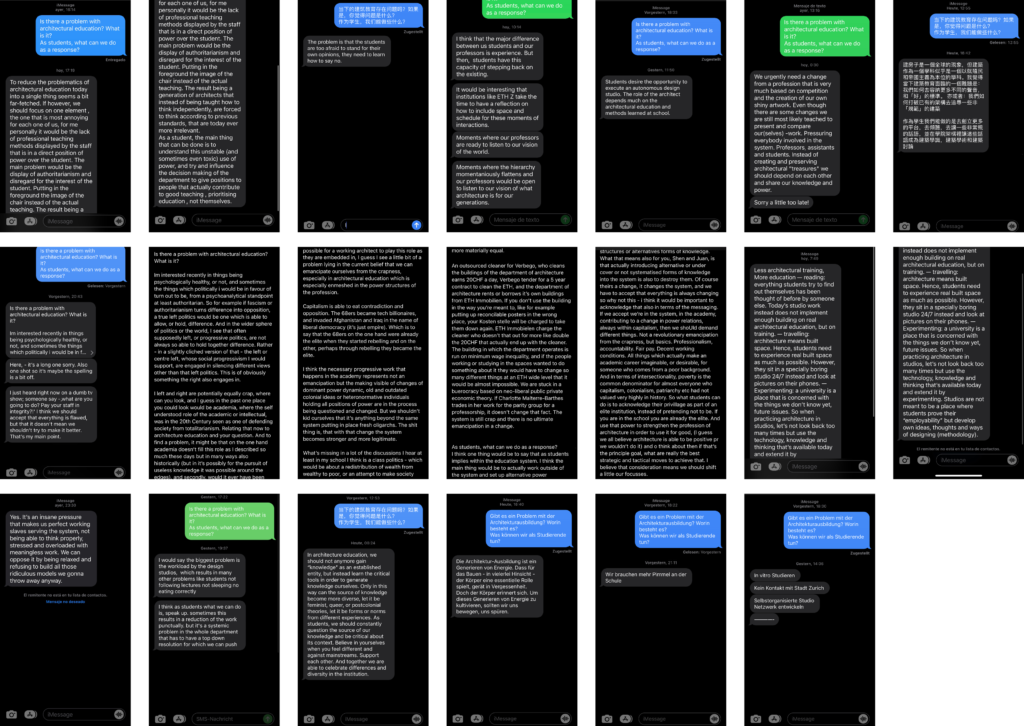

Ongoing SMS conversations on architectural education with our peers. View PDF to read further.