Global Tools: Dancing alone, clubbing together

Anna Moreno

Cover image: Space Electronic in 1970 (Archive 9999, courtesy Elettra Fiumi) In 2018, I started an investigation into Global Tools, a pioneering pedagogic project founded in 1972 by several architecture studios and individual practitioners belonging to the so-called ‘Italian radical design’ movement: Archizoom Associati, Remo Buti, Casabella, Riccardo Dalisi, Ugo La Pietra, 9999, Gaetano Pesce, Gianni […]

Cover image: Space Electronic in 1970 (Archive 9999, courtesy Elettra Fiumi)

In 2018, I started an investigation into Global Tools, a pioneering pedagogic project founded in 1972 by several architecture studios and individual practitioners belonging to the so-called ‘Italian radical design’ movement: Archizoom Associati, Remo Buti, Casabella, Riccardo Dalisi, Ugo La Pietra, 9999, Gaetano Pesce, Gianni Pettena, Rassegna, Ettore Sottsass Jr., Superstudio, Ufo and Zziggurat. Global Tools championed a reinstatement of manual work and the use of simple technologies, placing the body as the ultimate locale for architecture, a nucleus of latent political and creative potential. In response to what the group viewed as a conservative teaching tradition, Global Tools sought to reformulate the field as a political project by means of novel pedagogical approaches. Adopting an abstract, anti-didactic stance, they focused on everyday life with the aim of rediscovering a direct relationship between craftsmanship and product design, while also simplifying the design processes to counter the – then still incipient – production of plastic on an industrial scale.

My year-long research brought me to several cities in Italy to meet former Global Tools members Lapo Binazzi (UFO), Gilberto Corretti (Archizoom), Ugo La Pietra, Gianni Pettena, and Giorgio Birelli (9999), as well as Roberta Meloni, the president of the Centro Studi Poltronova. My approach as an artist differed from that of an architecture historian and delved into the subjectivities that enabled the emergence of the group as well as the reasons behind its short life span. That approach, I believe, is what gave me certain access into some poignant opinions of the protagonists about their own legacy. My starting point was the renewed interest those utopian ideas seemed to be garnering from the contemporary cultural field. The anarchist quality of the group’s experiments and the impact that the advent of interior design had on the discipline in the sixties and seventies became central to me, most particularly the irony of this group of soi-disant Marxists being so comfortable working for the luxury décor market. In fact, studios like Archizoom with their Superonda sofa (1968), the Misura series by Superstudio (1969-1972) and others, are examples of their prolific collaboration with high-end design firms like Poltronova, Olivetti, Zanotta, or Gufram.

Ettore Sottsass was then the artistic director of Poltronova, which was founded in Florence in 1957 by Lorenzo Camilli. The two championed the emerging works of young studios like Archizoom and Superstudio. They also commissioned Archizoom to design the company’s new factory and to program events there, which included a poetry and meditation workshop led by Allen Ginsberg. The Centro Studi Poltronova is now an archive and a showroom in the centre of Florence that still makes, on-demand, some of the iconic pieces created by the Radical Design movement and beyond. With their support, I designed and produced a modular four-piece sofa, very much inspired by Archizoom’s Superonda.

Left: Performance by Anna Moreno at the Space Electronic Club for Revival 9999 (2019), event produced for Radical Landscapes documentary, photos by Clara Vannucci. Right: Space Electronic in 1970 (Archive 9999, courtesy Elettra Fiumi)

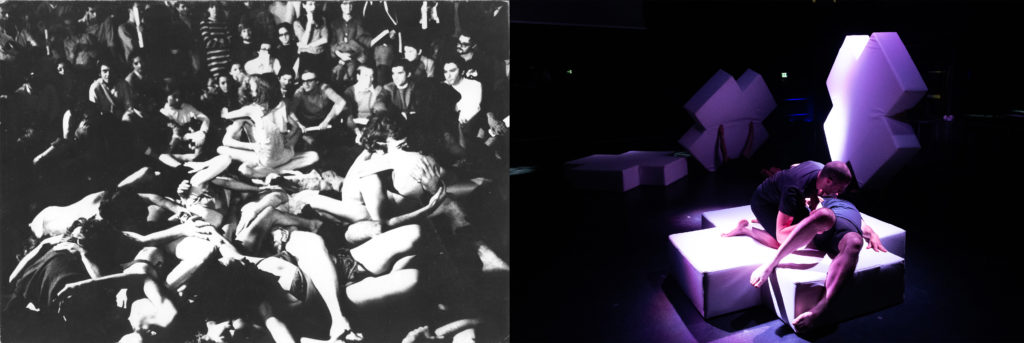

My sofa was then used as a prop during a performance at the Space Electronic Club in Florence, which once was the nucleus of Global Tools’ most radical experiments. The Space Electronic club was built in 1969 by the architects Giorgio Birelli, Carlo Caldini, Fabrizio Fiumi and Paolo Galli, under the name of Gruppo 9999, making the most of the Radical movement’s interest in nightclubs and influences ranging from New York’s Electric Circus to the theories of Marshall McLuhan. The club featured performances by US-based Ant Farm and The Living Theatre, among others, and The Mondial Festival included an elaborate programme with an experimental learning centre called S-Space: The Separate School for Expanded Conceptual Architecture, a clear precursor of Global Tools. There I first met Elettra Fiumi, daughter of Fabrizio Fiumi (a deceased member of Gruppo 9999), who was then researching her family’s archives for her future documentary film, named Radical Landscapes. As part of the club’s fiftieth anniversary, Elettra and I conceived an event with a series of installations and performances which set out to reprise the club’s influence on the underground scene of those years.

Left: Cover of the catalogue for the Superonda Sofa (Archizoom, 1967). Courtesy Centro Studi Poltronova. Right: Performance by Anna Moreno at the Space Electronic Club for Revival 9999 (2019), event produced for Radical Landscapes documentary, photos by Clara Vannucci.

While working on the prototype of my sofa with the CEO of Poltronova, Roberta Meloni, it dawned on me that she was a pioneer of her generation. She had wilfully gained the leadership of the Centro Studi Poltronova in Florence to bring back some of the radicality that had been lost after Sottsass. She was an inspiration to think about what it meant for a feminist visual artist like myself to re-think the legacy of the radical architects of the 70s, who could mainly sustain their practice due to a solid family support structure (caretakers and inherited wealth) and did not shy away from the infamous God-complex of the architect. During my research, I was not interested in ignoring the fact that Global Tools was an almost entirely white, male, bourgeois initiative that aimed to push architecture beyond design and engineering, proclaiming grandiose loosely Marxist-inspired mantras about society and its need for education. Under that light, I became interested in the motivations behind the recent mystification of 70s utopias and the lack of a critical approach on crucial factors of its emergence, like identity and geopolitics.

Visionary as they might have been, their focus on reclaiming the countryside and their admiration for radical pedagogic practices could be considered a mere aesthetic choice, as the group effectively fell apart carried away by their individual egos and careers before any of those practices were implemented. This is a harsh remark made to me by Gilberto Corretti, one of the members of Archizoom that I interviewed in his home in Florence three years ago. While sitting comfortably on an original Superonda in Corretti’s living room, its lavish red vinyl covered with a humble sheepskin, he invited me to travel back in time, some 10-15 years before the creation of Global Tools. Corretti situated the origin of the so-called Radical Italian architecture at a specific class of their school in Florence. Archizoom, Superstudio, and others were formed after a teacher’s group assignment to design a leisure facility. Amusement parks, resorts, and discotheques came about, and delight in collaborating and dreaming big erupted among the students. Gilberto pulls out a huge colour pencil drawing of a Luna Park with a large ferris wheel. That was Archizoom’s vision even before naming themselves Archizoom. Corretti recounts how the group moved their work to Pistoia in 1962, after a flood devastated the city of Florence, and how they then came together to exhibit their prototypes.

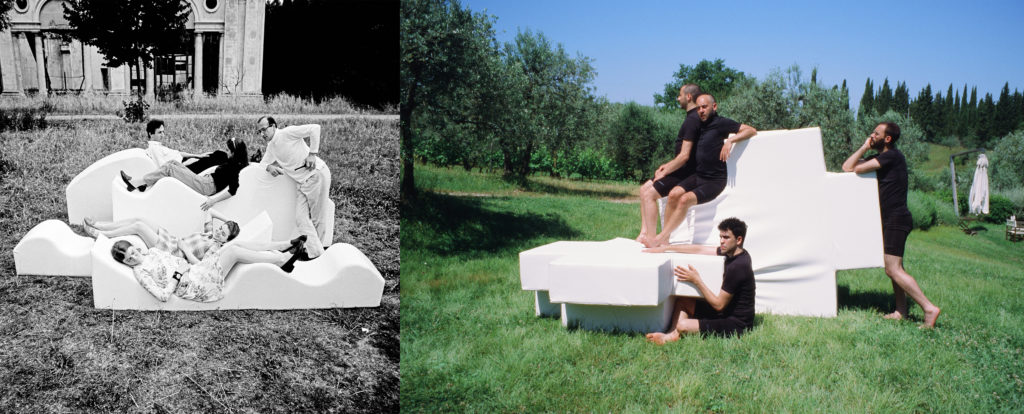

Superarchitettura (1966), in the wood workshop of a friend, was the infamous exhibition where the first Superonda appeared. The original one was made of wood and was so impractical it kept falling apart. It wasn’t until Ettore Sottsass brought the design to Poltronova that their experts decided to turn it into a polyurethane foam and vinyl combo, and to “slam it against the wall” as a quick fix for stability. Left: Superonda Sofa (Archizoom, 1967). Courtesy Centro Studi Poltronova. Right: Rehearsals of the performance by Anna Moreno at the Fiumi family Villa in Chianti (2019). Photo by Anna Moreno.

Even though Global Tools was not officially born until 1972, after several studios were invited to participate in New York MOMA’s emblematic show “The New Italian Landscape”, Corretti claims the flood to be the real origin of the group. Si faceva per noi stessi e ce lo mostravamo fra di noi: We did it for ourselves and we showed it among ourselves, he slurs. When I pointed out the pedagogical scope of Global Tools, he admitted that they ideated a school of alternative design not only to showcase and promote their own work, but to feel they were still alive by being together. Why a school then? I inquired. We made it an academy because that’s where it all started, he snorted, it was not an end in itself. One cannot be young at 30 with the same spirit of a 20-year-old. Because the 70s were already a different time, and during the show at MOMA it became clear that a tabula rasa was necessary. Corretti concluded that the birth of Global Tools “was marked by the end of enthusiasm towards a victorious capitalism.”

The day after chatting with Gilberto Corretti, I visited Lapo Binazzi in his studio in the centre of Florence. I wanted to grasp Global Tools political visions and dissect their understanding of the relationship between capital and society during that turbulent period in Italian history. Binazzi belonged to Gruppo UFO, a group born out of the wave of students’ protests and characterised by using irony and contestation in their public space incursions. While labour activists in Italy saw all of society as being pervaded by the logic and the methods of mass production, Binazzi, who was part of the team behind the theoretical development of Global Tools, turned this idea upside down: “For capital, it is not society that must become more like a factory, it is the factory that should resemble society”. Binazzi related that particular stance to the turmoil that Italy was subjected to during that time. Commonly referred to as the anni di piombo (years of lead), the 1970s have been seen as a parenthesis in Italian history, dominated by violence and terrorism from both extremes of the political spectrum. Those years also produced a vibrant labour movement with prolonged general strikes and the emergence of a unique, Marxist autonomist movement (best known through the Potere Operaio, Lotta Continua, and Autonomia Operaia political parties). In 1969, with the autonomist student movement being particularly active, the protests led to the occupation of the Fiat Mirafiori automobile factory in Turin. Global Tools members such as Lapo Binazzi and Gianni Pettena actively participated in the protests with interventions that later became raw material for the collective imaginary of the group. Gruppo UFO’s urban activities were intended to bring about a spectacularization of architecture, in the hope of transforming it into urban and environment “guerrilla” action. Precarious materials like paper-mâché, polyurethane, clay, inflatables, were given a new protagonism. Their performative analyses of the rural territory greatly influenced Global Tools’ distinct interest in the Florentine countryside, where we can find one of Global Tools meeting spaces: a farm in Sambuca, in the Chianti region, belonging to the family of Roberto and Alessandro Magris (Superstudio).

Left: Superonda Sofa (Archizoom, 1967). Courtesy Centro Studi Poltronova. Right: Rehearsals of the performance by Anna Moreno at the Fiumi family Villa in Chianti (2019). Photo by Anna Moreno.

In 1974, Global Tools organized their first and only seminar in Sambuca, where all members met with their families in a sort of hippie commune, setting the bases of the nomadic school that never came to be. During those days, Remo Buti gave a workshop on clay, and the group constructed home-made hot air balloons, producing the famous cover of Casabella magazine showcasing Sottsass flying up one of them in the garden at Sambuca. Their methodologies establish immediate links to other contemporary countercultural movements such as The Whole Earth Catalogue in the US, for their invocation of technology as a means to reconcile independent living and material knowledge. However, Global Tools’ contribution was largely more radical and performative: the group was divided into working sections that were supposed to produce their own individual laboratories, named ‘The Body’, ‘Construction’, ‘Communication’, ‘Theory’, and ‘Survival’. However, the group fell apart way before those workshops had progressed beyond the first session devoted to ‘The Body and the Bonds’. Nevertheless, the discussions surrounding its formation provided a launching pad for the emergence of studios like Memphis and Alchimia in the 80s. Inspired by the workings of Global Tools in Sambuca, Elettra Fiumi and I decided to temporarily inhabit another countryside house in the Chianti region that belonged to the Fiumi family. There, during the week that preceded our performance at the Space Electronic Club, I gathered with choreographer Matias Daporta, and performers Vincent Giampino, Pablo Durango, and Andrea Dionisi, who would make my Poltronova sofa come alive.

Left: Rehearsals of the performance by Anna Moreno at the Fiumi family Villa in Chianti (2019). Photo by Anna Moreno. Right: Superonda Sofa (Archizoom, 1967). Courtesy Centro Studi Poltronova.

The day after talking to Binazzi, I went up to Fiesole, in the Florentine region, to meet with artist Gianni Pettena in his studio. Permanently holding a half-consumed cigar, Pettena is convinced he is the only real artist in Global Tools. He affirms he always felt like an outsider in the group and produced what became, in my opinion, symbolic evidence of the inherent divisions within them that eventually catapulted their dissolution. During the meeting in Sambuca everyone posed for a group picture, and Pettena held up a sign reading “io sono la spia” (I am the spy), which was met with disdain by Superstudio: You ruined the picture! Emmanuele Piccardo, a curator and photographer of architecture who was a direct witness of the work of Pettena and Robert Smithson during his American incursion, shares this vision of the group’s dissolution. Piccardo is well versed in the personal intricacies of the group and was my closest accomplice in getting me to meet all of them in person. He is convinced that Global Tools’ ultimate break-up was provoked by an internal division between the Florence-based faction of the group and the other fiorentini who had emigrated to the capital, Milan. The latter were perceived as bourgeois and therefore more concerned with both conceptual and commercial questions regarding industrial design, while the former claimed to be the real ideologues of the group, wanting to maintain their political and artistic essence regarding craftsmanship.

According to Lapo Binazzi, l’artigianato (craftsmanship) did not know how to renew itself from a conceptual standpoint. Radical utopia and built architecture, he stated, were and always will be in conflict. In that regard, I find the Giro d’Italia (1971) one of the most emblematic performances of the UFO, which in turn serves to illustrate the ambivalent relationship of the group with the rural, while pinpointing to their enthusiastic embrace of an ephemeral, performative architecture. They dressed up with cyclists’ attire and proceeded to tour the countryside, breaking the rules of road etiquette and routes: they would criss-cross over vegetable gardens and climb electric towers carrying their Campagnolo bikes on their backs. Their final destination: The Space Electronic nightclub in Florence, where the cyclists would erupt during the Mondial Festival in 1970.

Left: Performance by Anna Moreno at the Space Electronic Club for Revival 9999 (2019), event produced for Radical Landscapes documentary, photos by Clara Vannucci. Right: Performance by the Living Theater at the Space Electronic Club during the Mondial Festival in 1970 (Archive 9999, courtesy Elettra Fiumi)

Left: Performance by the Living Theater at the Space Electronic Club during the Mondial Festival in 1970 (Archive 9999, courtesy Elettra Fiumi). Right: Performance by Anna Moreno at the Space Electronic Club for Revival 9999 (2019), event produced for Radical Landscapes documentary, photos by Clara Vannucci.

The Florentine discothèque became the breeding ground for the type of multipurpose and interactive happenings that characterized the Italian Radical movement. Somehow, the club amalgamated all those initiatives in a similar way that the Global Tools project did. If there is one common thing in my conversations with its former members is that they all made reference to their individual practices, and how Global Tools produced a context for them to become pedagogical instruments. In a way, form seemed to precede over content. Or better put: the medium was indeed the message. What astonished me during the interviews I conducted then, is how some of the original members of Global Tools are still now quarrelling about the authorship of the original idea. I wonder if the reason is how in recent years utopian projects from the 70s have gained a new relevance, or the fact that we now lack those grand narratives for future imaginations. Ugo La Pietra was not amused by this utopian revival. In his Milanese studio, he grunted that younger generations are lacking imagination and hinted to certain architecture historians as predators. When Elettra Fiumi and I staged our tribute festival at the Space Electronic Club 50 years later, we attempted to re-propose the spirit of the radicals and what it would mean to our generation. Especially when growing vegetables in a basement, flooding a dance floor, and tossing a sofa in the air appear to still be radical architectural proposals nowadays.

Left: Space Electronic Club in 1970 (Archive 9999, courtesy Elettra Fiumi). Right: Performance by Anna Moreno at the Space Electronic Club for Revival 9999 (2019), event produced for Radical Landscapes documentary, photos by Clara Vannucci.