The concreteness of learning: Peter Zumthor’s primo anno course at the Academy of Mendrisio

Rafael Lorentz

As we can tell from our own lives, brief moments of intense experience are often the ones that most decisively define our perception of reality in the long run. In the field of architectural education, an interesting case where ephemerality was explored as a strategy of intensification can be found in the teaching activity of Peter Zumthor in the Academy of Architecture […]

As we can tell from our own lives, brief moments of intense experience are often the ones that most decisively define our perception of reality in the long run. In the field of architectural education, an interesting case where ephemerality was explored as a strategy of intensification can be found in the teaching activity of Peter Zumthor in the Academy of Architecture in Mendrisio. Although his presence in the school from 1996 to 2007 represents a widely known fact – particularly widespread with the publication of the essay Teaching Architecture, Learning Architecture as part of his best-selling Thinking Architecture1 – little attention has been given to what could be called the most ambitious and revealing act of Zumthor’s pedagogical approach: the atelier he set for first-year students in the academic years of 1996-97, 1997-98 and 1998-99.

The study of this seminal event was made possible by the rediscovery of the archives of Atelier Zumthor kept in Mendrisio, where the documentation of its activities – including items such as teaching journals, exercise reports and over 4.000 photographs of student works – remained silent for the last two decades. There are no clear reasons for this oblivion. On the one hand, Zumthor himself seems to have lost interest in claiming the material as part of his own intellectual oeuvre.

On the other, his withdrawal from the Academy was followed by the progressive erasure of all physical traces of the archive – including original models – allegedly due to the difficult conservation conditions required by their materiality. Such abandonment is all the more hard to understand if we consider that the construction of the archive was consciously planned by Zumthor as a necessary tool to communicate what he considered to be an educational experiment. In that sense, today’s critical reconstruction of Atelier Zumthor is based precisely upon the accuracy with which its activities were described and assessed – something that also indicates how ambitiously teaching was taken as a privileged space for conceptual research.

A fundamental instance explored in the conception of Zumthor’s primo anno course was the temporal dimension of learning. It informed not only the delimitation of a three-year time frame for the ‘experiment’ to take place, but also the creation of a didactic structure based on brief exercises which were designed as true events. Aimed at first-year students, this sequence of 19 exercises was aimed to teach what was defined as ‘the foundations of composition’,2 i.e. the most radical knowledge upon which architectural training would later evolve. This notion of ‘ground zero’ represented for Zumthor an unique opportunity to develop a didactic that intentionally avoided all kinds of academicism – doomed as something ‘abstract’ and therefore non-reliable – by assuming a ‘concrete’ approach whose legitimacy stemmed from its ‘self-evident’ condition. Taken as architecture’s primary quality, ‘to be concrete’ stood thus as the conceptual cornerstone of Atelier Zumthor, defining a phenomenological approach in which all instances of the educational process were constantly referred to the student’s experience of the world.3

This is visible, for instance, in the emphasis given to sensory perception as a fundamental theme of the course. Particularly evident in the structure of the first year, many of the proposed exercises were developed with the intention of making students aware of the value of their five senses. In that regard, it might be said that their own bodies represented a central instrument in the atelier, explored as main mediators between the project and the object’s factual qualities. Besides this instrumental frame, the absence of external references to validate students’ work seems to have also lent a particular importance to authoriality as a project’s positive and expected value. In other words, while institutionalized training in many architecture schools tends to promote equal and standardized education – often understood as their main duty – every activity of Atelier Zumthor was aimed at encouraging students to explore personal expression as a necessary quality of design.

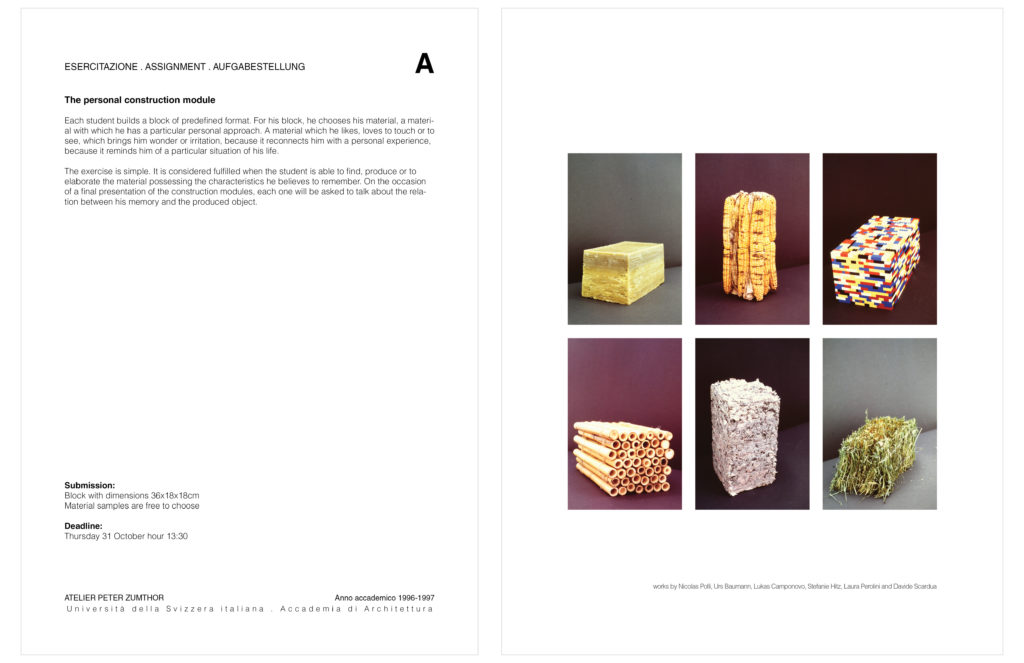

An illustrative example of the atelier’s structure can be found in the sequence of exercises developed along its inaugural year. The first exercise, called The personal construction module (A), required students to build a block with given dimensions using a material that should tell the content of a personal experience. The apparent simplicity of the task condensed a much deeper process, starting from the selection of a biographical memory to be presented, then followed by the identification of the role played by a specific materiality in its conception.

A former student told how, from the experience of penetrating a grass field as a child, he produced a block built as a dense weave of grass branches. Another student, whose memory was that of walking on a melting sidewalk during a hot summer day, built a block entirely made of asphalt. Important, however, was not the material itself, but the effective experience it could convey, bringing characteristics like scent and touch to be central components of the constructive challenge. Therefore, the grass block should contain the scent of a spring Alpine morning, just as the second one had to smell like melting asphalt. The exercise’s fulfillment was assessed in the block’s capacity to communicate the content of the experience in such a way it was understandable to the entire audience. Ultimately, materiality acted as the mediator of a transformation process that translated a highly individual image into something collectively graspable.

Exercise A: The personal construction model

The importance given to presentation as a moment of verification was transversal to the atelier. In 100 steps for a blind (B), the second exercise, students should design a tunnel connecting a town to a park, imagining how a blind person could find orientation inside it. The final submission consisted of a resonance body – a model at 1:20 scale – which was then put to a real sound test. Projects tended to explore different materials and morphologies as a means to obtain different acoustic responses, as in the case where a crescent scale of voids was carved beneath a wooden floor inside the tunnel, generating a progressive change in the reverberation of steps guiding the blind walker. In An indirect-lighting lamp (C), a lamp should be built using a given set of materials and following a set of rules such as “the lamp must not be seen” and “use simple forms”. More important, however, was the fact that the lamp was meant to work effectively, stressing how much the practical challenge stood as one of the atelier’s main mottos. The closing exercise of the first semester was called The fragrance and aroma street (D), requiring the construction of a small shop containing a product characterized by a particular scent, in such a way designs were developed as aroma-driven strategies.

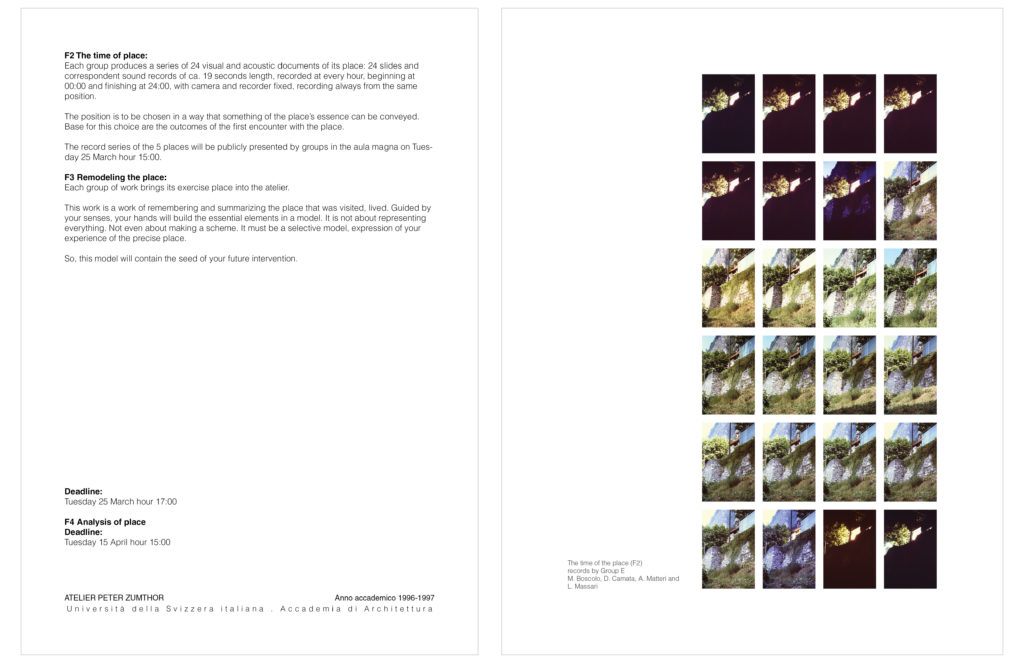

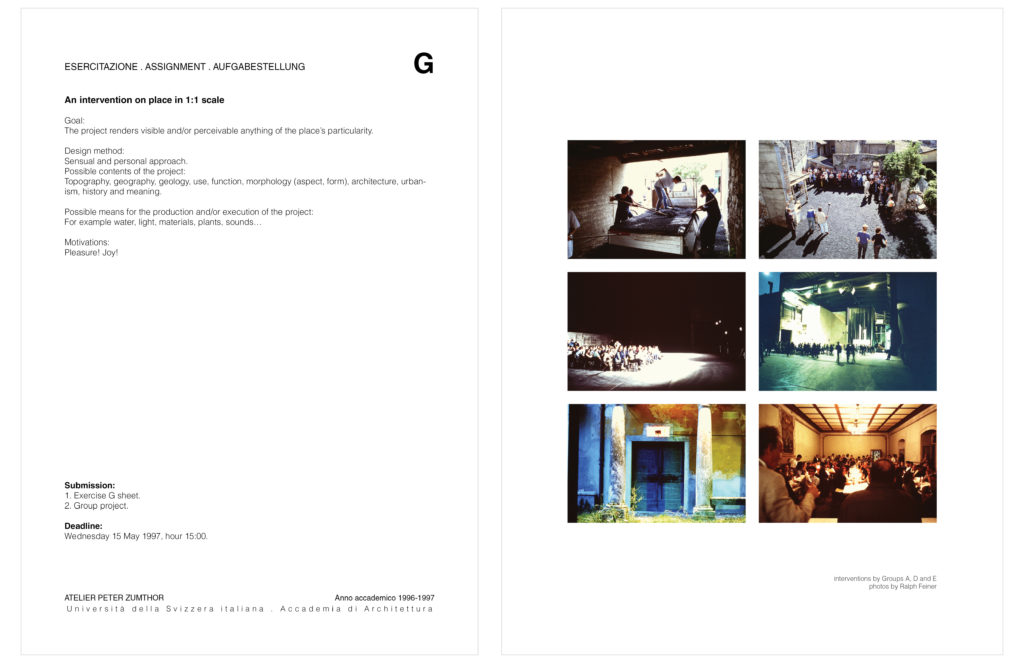

Moving on to the spring semester, a transition in complexity reached the scale of the territory in the exercise In Situ (F). Divided into groups, students were given a specific site to work with, representing typical situations of the school’s surroundings. The First encounter (F1), where each student visited his place individually, was followed by The time of the place (F2), requiring each group to produce a series of 24 documentations of the site – hourly records made with a fixed camera during the period of a day. An intervention on place in 1:1 scale (G) closed Atelier Zumthor’s first year, asking groups to operate a ‘concrete’ transformation in their sites, in such a way to “render visible or perceivable anything of their particularity”.4

Exercise G_ An intervention on place in 1_1 scale

In what can be read as a condensed depiction of the course’s didactics, students conceived their projects as interventions whose material presence was directly conditioned by a temporal narrative. This is visible in the work produced by Group C on a peripheral plot near to the highway exit to Mendrisio. It took advantage of the steep topography to design an intervention made of 300m of flexible light tube installed over the slope in the shape of a huge heart. The original form, however, could be seen only from a sighting platform on top of Monte Generoso – from the site itself, the tubes were perceived as the chaotic intertwining of light strokes. The design concept was based precisely on the changing perceptions of the landscape, and executed through the temporal experience of an audience that climbed the mountain by night to behold the glowing heart in the valley below.

This sort of ceremonial dimension was evidently present along the atelier, helping to create its own identity as a special, unrepeatable event in itself. In fact, the deep personal involvement required by Zumthor’s approach led students to adhere to his atelier – or to withdraw from it – with much more intensity than the usual experience of an architecture school. The enthusiasm that emerges both from the archive’s documentation and the testimonies of former students and assistants is clearly linked to what Aurelio Galfetti referred to as “the feeling of being part of something absolutely new”.5 An important part of this atmosphere of excitement stemmed from the fact that the atelier would exist only during a limited amount of time – as already mentioned, a three-year period. In that sense, the decision of repeating the course for three times had certainly some relation to the growing pace of the school itself – which at the time had not reached advanced years. However, the choice for such a specific structure also contained the ambition to delimit a reality possible to be critically observed.

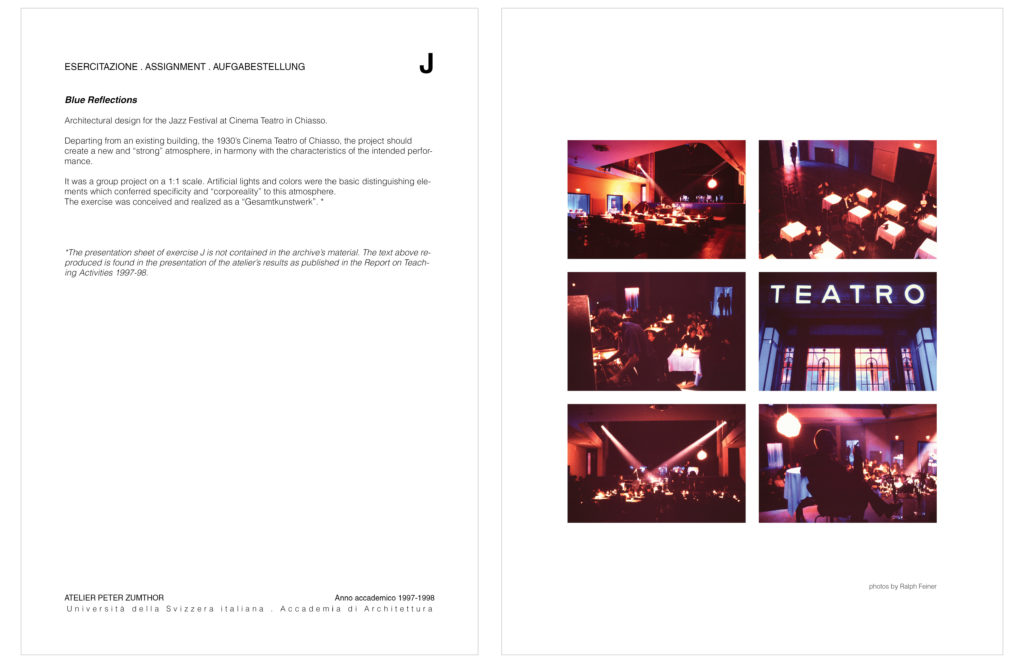

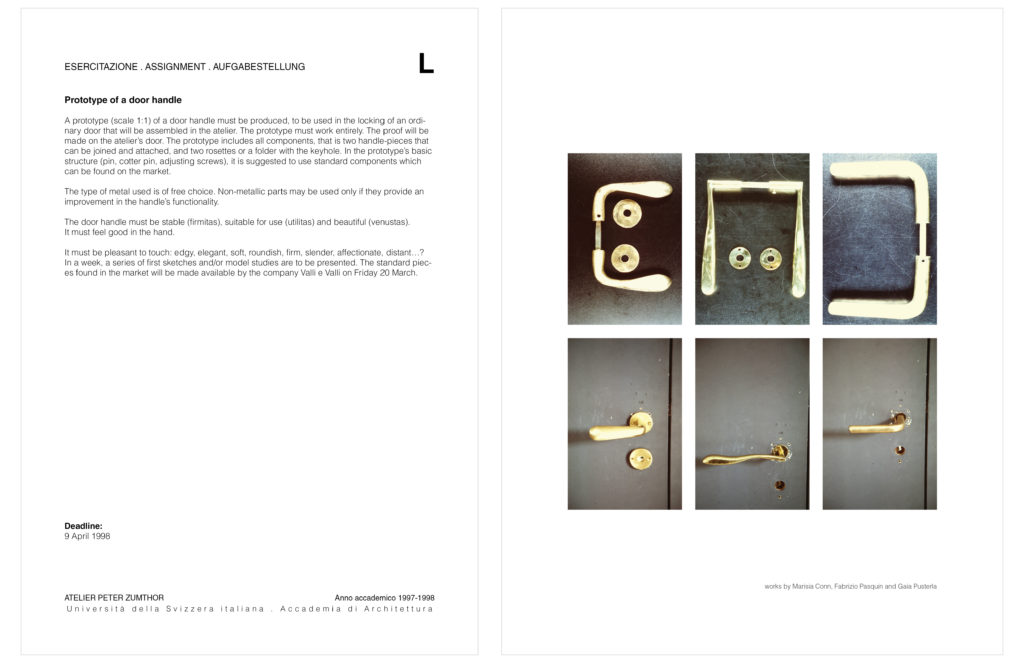

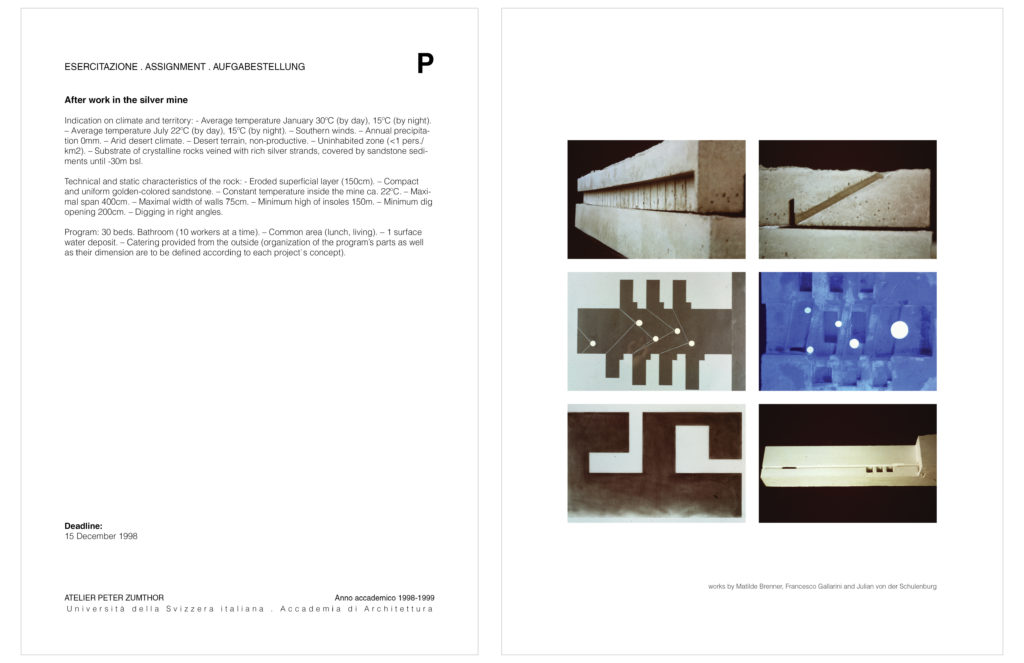

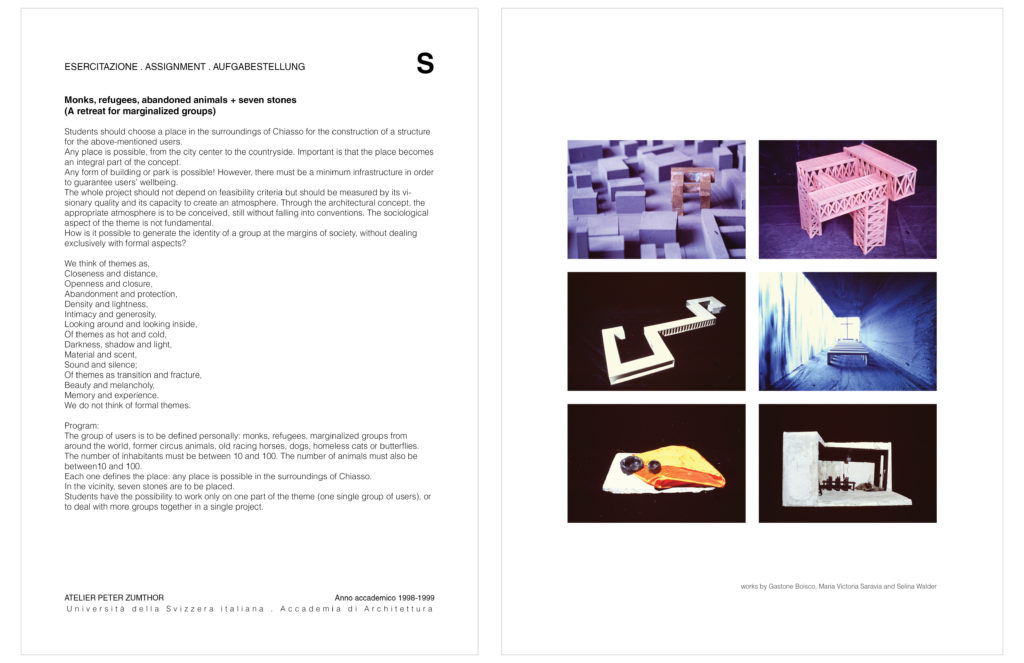

The second and third years of Zumthor’s primo anno course shared the same basic structure of the first year described above, with conceptual exercises followed by operations at territorial scale. A slight differentiation, however, is visible in the last year, which contains not only less exercises than the others – 5 instead of 7 – but also seems to seek an approach more closely related to the nature of an architecture project. In that sense, while the second year (1997-98) was characterized by performatic exercises such as Blue Reflections (J) and Prototype of a door handle (L), in the third year (1998-99) the central object of most exercises could be identified as a building – as in After work in the silver mine (P) and Monks, refugees, abandoned animals + seven stones (S).

In spite of any parallel between the years, exercises were never repeated in Atelier Zumthor, as they represented the creative instance of the teacher’s work. In that sense, it is important to mention that assistants played a central role in the atelier, not only as operational figures but really as co-authors of the educational project. The original group of assistants of Atelier Zumthor was formed by the sculptress Miguela Tamo and by the architects Thomas Durisch, Pia Durisch and Miguel Kreisler – the latter of which the one officially in charge of the atelier in Mendrisio. As the course started in the Fall semester of 1996, there was no such thing as a preconceived list of exercises. Instead, each of them was collectively conceived by Zumthor and the assistants, observing the interaction between their initial inputs and the response given by students.6 Understanding this dynamic brings light to the archive’s value as the record of a progressive reasoning, stressing how much teaching was seized by Zumthor as an opportunity for theoretical reflection. Read in reverse, the sequence of exercises reveal a set of concepts that can be found in the base of his own architecture, such as the assumption of biographical memories as a source of typical images and the use of construction as the primary form-giving process of design.

Certainly, the analysis of Atelier Zumthor as a pedagogical project must take into account the particular conditions from which it emerged. The most defining of these is the fact that Zumthor was in charge of one of the three foundational ateliers of the Academy in Mendrisio – along with Mario Botta and Aurelio Galfetti. This means that the originality of his methodology was a direct reaction to the freedom of experimentation granted both by the school’s humanistic program and by the need for affirmation characteristic of a newborn institution. Looking at Zumthor’s primo anno course from a distance of 25 years, it seems possible to say that its emphasis on the individual dimension of learning is something increasingly hard to reproduce in an educational environment progressively conditioned by standardization. At the same time, the definition of embodied perception as the discipline’s primary interface and the valorization of architecture’s communicative dimension as a condition for its cultural relevance are lessons whose pertinence has only grown over the years. Considering the inevitable pressures to which all forms of education will be exposed in the near future – among which the intensification of remote teaching is only the most visible – the experience of Atelier Zumthor in Mendrisio may very well remain as a half-forgotten memory remembering us that learning is a non-transferable personal act.

Atelier Zumthor AAM, primo anno exercises in sequence:

1996-97

A. The personal construction module

B. 100 steps for a blind

C. An indirect-lightning lamp

D. The aroma and fragrance street

E. Nature, street, house +1. Video-project

F. In Situ

G. An intervention on place in 1:1 scale

1997-98

H. A space that looks at the landscape of my youth

I. A window for my friends, to read by the light of the lake

J. Blue Reflections

K. The typical space

L. Prototype of a door handle

M. A tableau vivant in Laveno

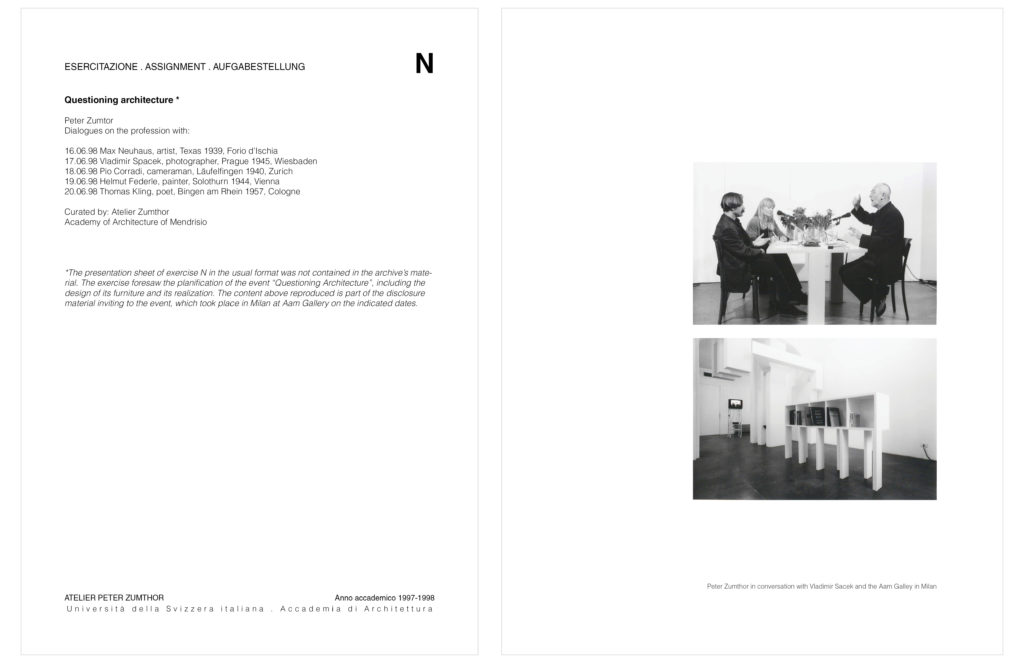

N. Questioning architecture

1998-99

O. A Miniature

P. After work in the silver mine

Q. The love for things, after work in the silver mine

R. Intermediate exercise from 4.2.1999 until 8.3.1999

S. Monks, refugees, abandoned animals + seven stones