Broken love machine, or how to live a great love

Woman’s Torso

We pressed our hands against the stone and, as in a single move, we jumped over the wall. Without believing that I was already on the other side, I lowered myself subtly to notice some difference between the worlds. When fear reaches the limit, it becomes a beast. The feeling of death that fear causes […]

We pressed our hands against the stone and, as in a single move, we jumped over the wall. Without believing that I was already on the other side, I lowered myself subtly to notice some difference between the worlds. When fear reaches the limit, it becomes a beast. The feeling of death that fear causes petrifies the bodies, mutes the subjects, turns them into objects, into statues, but in fear there is also a breath. It seems that the skin becomes thinner, the internal organs wake up and the body is more sensitive to adrenaline. On the other side of the wall, the house produced a curious fascination. Around and even inside it, a series of female granite and bronze sculptures were present. The figurative sculptures, combined with the house’s abstraction, seemed to inhabit in silence. One could say that it was Perseus’ own curse against Medusa, but perhaps it was something else entirely. Next to the rock that merged architecture and local geology together laid two brooms and a barrel of garbage, a woman’s torso and a reclining woman, leaning against a light veil carved in the nakedness of its body. As we moved, other women emerged. We danced around these split-body objects, relating to each missing curve while I filmed in motion. Being there brought a sense of desecration of something, even if quietly, even if out of sight. Nina moved subtly, slowly and in silence, mirroring her movements to those of the sculptures, continuing what had been interrupted or petrified. Like the white of architecture, the white of our garments was gradually soiled with mosses and lichens. Dancing with the statues was liberating; it seemed that it gave life to those forcibly inanimate beings, evoking another body presence.

The patriarchal house

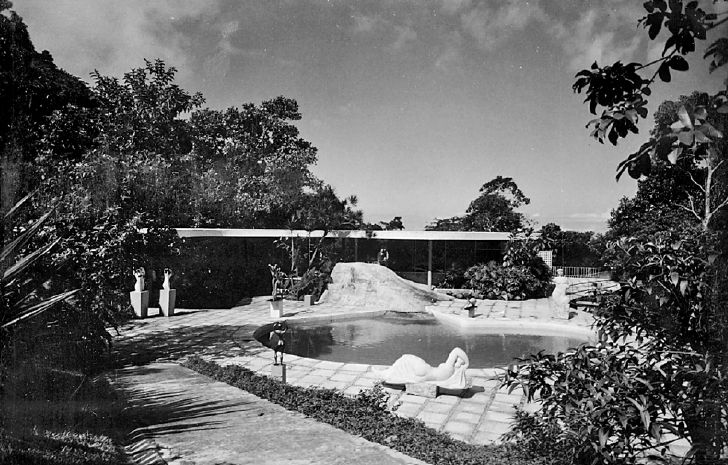

Designed by the architect Oscar Niemeyer in the 1950s and built between 1951-1953 in Rio de Janeiro when the city was still the capital of Brazil [between 1763-1960], Canoas House was the architect’s residence for six years with his daughter Ana Maria and his wife Anita, before going to Brasília to accompany the construction of the country’s new capital. A preliminary survey of the house is manifested by a series of characteristics that gave the author a name of national and international recognition: sensuality and eroticism materialized by the relationship with the beauty of the curved and organic forms of women, as well as the natural landscape of Rio de Janeiro.

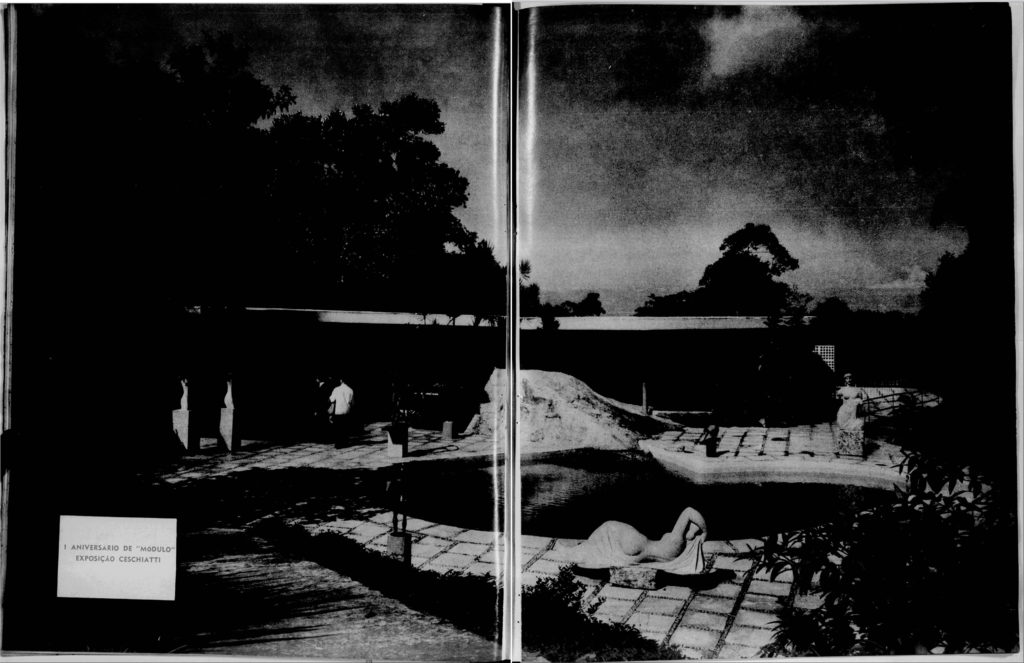

Marcel Gautherot. Alfredo Ceschiatti, 1956. IMS Collection

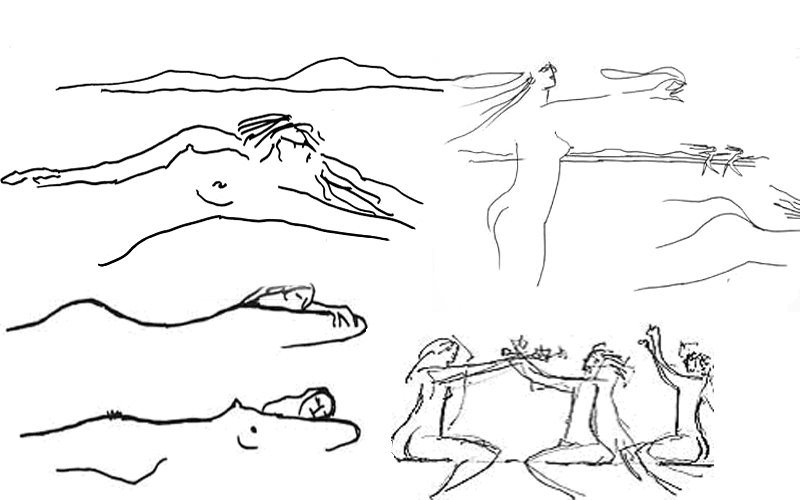

The relationship between loving muses and nature is not fortuitous. Nature has, for centuries, been continuously associated with the virginal love-giving female body. The representation of women, for example, in 19th century landscape painting brought together the concepts of nature, women, motherhood and the “natural” feminine. In the Brazilian romanticism of European influence, the painting “A Carioca” (1882) by the artist Pedro Américo (born in Paraíba, 1843-1905), can be an example, as so many others. The relationship between the pure woman, with white and glossy skin, the bowl dripping with water, sensuality and even masked sexuality, evoke the construction of a moral femininity associated with an equally pure and fertile nature. Coming from a fundamentally masculinist gaze, the representation through the horizontality of the bodies of both architecture, nature and women in Niemeyer’s sketches reinforce this paradigm. But if the sensuality of Niemeyer’s curves showed the woman as landscape by associating body and nature, on the other hand, it perpetuated oppression against women’s bodies confining them to their sex and reproductive means. In this sense, love is materialized by a compulsory heterosexuality, as in its most known poems: “It’s not the right angle that attracts me,/ Nor the straight, hard, unyielding line created by man./ What attracts me is the free and sensual curve./ The curve that I find in the winding course of our rivers,/ in the clouds of heaven, on the body of the favorite woman./ The whole universe is made of curves,/ Einstein’s curved universe.”1

Marcel Gautherot, Alfredo Ceschiatti’s Sculptures, 1956. IMS Collection

However, the enunciation of love as a cultural deed dates back from antiquity. Eros, the god of Love in Greek culture, was paid a compliment by Plato’s “The Symposium” in 380 BCE. Love was built through different narratives and discussed by men, among men since women were excluded from collective debates. Plato’s readings of Eros can deepen the understanding of how Niemeyer’s modernity perpetuated and translated its affections. Eros, when incarnated by his modernity, assumes universalizing and masculinist garments, playing a fundamental role in perpetuating a sexual division into binarism even when gender and sexuality are made invisible functions within the constructive mechanism of modern architecture.

Within architectural modernity, in 1917, Le Corbusier had published Towards an architecture, where he exposed the idea of a house as a Machine for Living in, which had an enormous influence in Brazilian modernism. However, outside the domain of reason, Niemeyer’s alleged modern sensual tropicalism, which enchanted many modernists, evidently arises from an epistemological ethos that embraces modernity within a fundamentally masculine system, masked as universal. When coining the title of a national hero of architecture, through a self-centered masculinity, a characteristic that accentuates the value of the demiurge architect, one can feel doubts about his sensualization of modernism, arising fundamentally via a white, masculine, patriarchal European matrix.

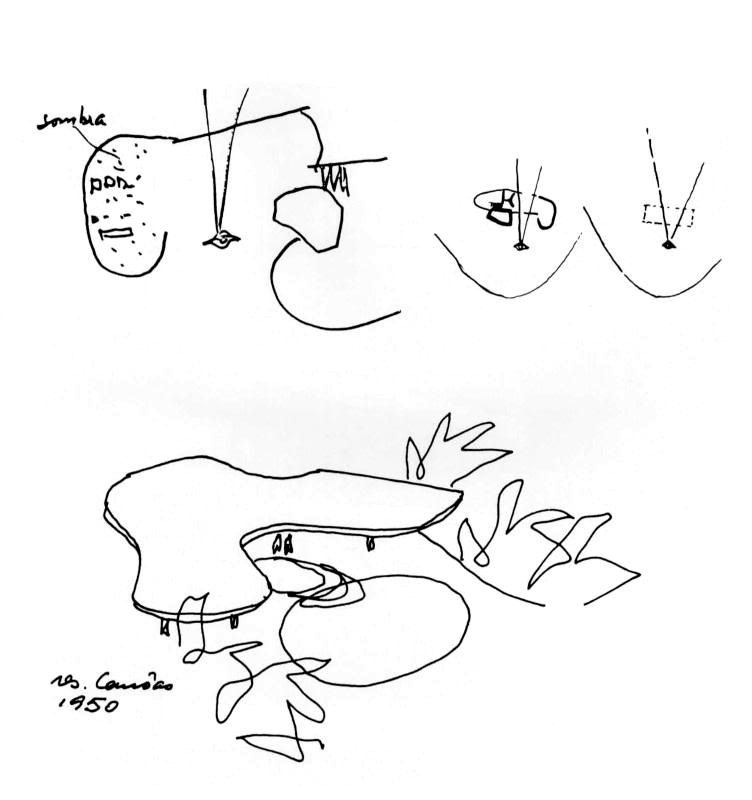

Oscar Nyemeyer’s sketches

Patriarchy, as Gerda Lerner recalls, is a historical creation formed by men and women in a process that took about 2500 years, based on the commercialization of female sexuality, and on the transformation of women into a resource enchanted by class differences, which according to her, is expressed in terms of gender. Women themselves became a resource, acquired by men. The architecture could not be indifferent to the current sexual system, to the extent that one could call it the modern patriarchal house.

The role of this tropical modernism didn’t look upon the patriarchal eroticism pointed by the objectification of the women’s bodies, that became hegemonic in a place of construction of a national identity. The discursive, imagetic and ideological construction of it can be seen in the encounter of media from the Exhibition of Alfredo Ceschiatti, in 1956 at Niemeyer’s House.

Marcel Gautherot, Alfredo Ceschiatti’s Sculptures, “Bather”, 1956. IMS Collection.

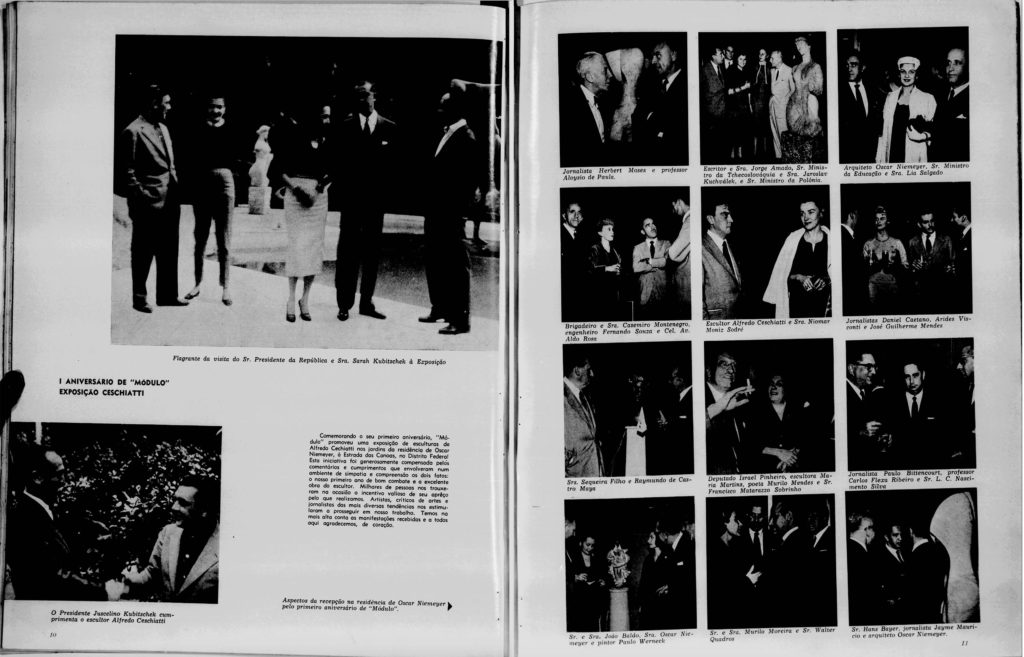

The exhibition

Different from the usual sites of art exhibitions, the one made by Alfredo Ceschiatti, an artist known for the sculptures to be settled in Niemeyer’s buildings, was displayed in the Canoas House’s interiors and gardens. The exhibition was published in the fifth edition of Modulo (The Magazine of Architecture and Visual Arts of Brazil), of which Niemeyer was editor-in-chief, in order to celebrate its fifth anniversary, and the displayed photographs in the Magazine were taken by Marcel Gautherot, a French photographer based in Brazil, who played a fundamental role in documenting the images of a national modernity. Beginning to circulate in the year of the inauguration of President Juscelino Kubitschek (January 31, 1956), the exhibition and the publication are important archives in considering the construction of a modern and public body which contradicts the notion of the house as a private domain.

5th Edition of Modulo Magazine, 1956 – Anniversary of Modulo, Ceschiatti’s Exhibition (pages 8 and 9). National Library Collection

The house was divided into levels that separate dialectically what is shown and what is secret. While the compartmentalized spaces of intimacy are hidden by the new topography of the house, the free design of the ground floor, held by the spaces of sociability, become stage for this great constructed scenario. This space becomes a voyeuristic exhibition device, both of a built femininity exposed by the figurative sculptures, as much as of the free forms of architecture. Within that, there is a tension between the exposure of a sensual body, in the public sphere and the control of the body in the private sphere. This is evident from the fragments registered and chosen to appear in the Modulo Magazine. Accentuating the patriarchal domination present in modernity, the house is revealed through the vision of an idealized heterosexual love, where the space of sociability is given by the transparency and abstraction of the forms of a white, ethereal femininity. Within that, there is a subjective evidence of the architect’s point of view under a platonic sense of femininity and love.

5th Edition of Modulo Magazine, 1956 – Anniversary of Modulo, Ceschiatti’s Exhibition (pages 10 and 11). National Library Collection

Not only does the architecture have a role of seduction through an imported myth of femininity, so do the sculptures. In this magazine edition, were seven highlighted sculptures: Acrobats, Liliane, Bather, Rooster, Fish, The Three Graces, and Woman’s Torso. Contemporary Brazilian critics might have pointed out the importance of the feminine nudes, its “voluptuous and sexualized” bodies, its adornment function, the woman and its single function of pleasing the men’s universes or even the friendship pact between men that had women sculptures as a trademark. In this sense, the culture of fetish offers a parallel with the culture of the commodity present between the 19th and 20th centuries. Rethinking the use and fetishistic cult of the female body as a formal operation in architecture, it is imperative to rethink the cultural parameters between the feminine as a natural body and merchandise, especially since architecture in a capitalist context makes it the hallmark of a culture, an advertising body. This is especially important when Niemeyer tells in his memoirs books he was invited by Juscelino to build Brasilia in the after-party of Ceschiatti’s Exhibition. Within that, one could argue that in an important political context, that would lead to the building of the new Capital Brasilia, the house functioned as a seductive device.

As Judith Butler already pointed out, beyond culturally constructed or naturally given, gender is social performance. For her, “the sex/ gender distinction suggests a radical discontinuity between sexed bodies and culturally constructed genders” meaning that “when the constructed status of gender is theorized as radically independent of sex, gender itself becomes a free-floating artifice, with the consequence that man and masculine might just as easily signify a female body as a male one, and woman and feminine a male body as easily as a female one.”2 (Butler, 1990, p.6). In this sense, it is worth considering: how were images of seduction, historically attributed to femininity, used in the new designs of modernity and permeated in the active circuits of power, dominated by men? How does architecture build the category of sex? How does it perform a gendered body, and what is its impact in the context of building a national identity? How do these subjects participate in the type of pleasure offered when looking at the house, and how do they announce fantasies through power?

1950 Oscar Niemeyer’s sketch of Casa das Canoas

Much is known about Niemeyer building his persona through anecdotes of youth, his participation in the “Clube dos Cafajestes” (The Womanizer’s Club), his sexual experiences in Lapa, the meeting with the women on Wednesday’s nights, the jokes in the office he shared with Jorge, Reidy and Hélio at Nilo Peçanha, where, as he tells in his memoirs books, gathered friends such as Vinicius de Moraes, Carlos Leão, Echenique, Luiz Jardim, Eça, Duprat and Cavalcanti.

It is worth reminding ourselves that in the art scene of the moment, Bossa-Nova was a genre of music pretty much growing in the same space-time of the house – a Rio de Janeiro of 1956. The so sounding words of “Pra Viver um Grande Amor” (To live a great Love), by Vinicius de Moraes exposes the limits of this idealism: “To live a great love/ First you have to be a gentleman/ And be your lady’s whole/Whatever it is/ We must make the body an address / Where the beloved woman is cloistered/ And stand outside with a sword/ To live a great love”3

Not much different from the love song by Vinicius de Moraes, Niemeyer has built for himself a love machine. The lustful and imaginative being, as he himself says, led him to “the paths of sex, architectural invention and fantasy”4. What it seems is that his double-persona allows him to be the playboy in architecture, even if he has built a family home for himself. The space of the modern playboy architect is the space of the erotic masculine, the sensual, permissive and public and it is positioned – scenically – the heteronormative and patriarchal family life. When building an erotic apparatus, from the masculine sense, materialized in the violent objectification of a body, architecture becomes the platonic woman built for himself.

Alfredo Ceschiatti’s Sculpture Woman’s Torso, 1956. Photo by MarcelGautherot. Source: Instituto Moreira Salles Collection

In the myth of Daphne and Apollo, it is by turning into a forest that Daphne manages to outwit the enemy from abuse. The forest here also acts as a defense, a shield for the simulacrum, for the very chaos it entails. This may also be a track where the erosion of a sort of heteronormative culture resides. The category of woman, unlike a return to an origin, to an ornament or to a petrified state, is a performative multitude against its violent objectifications and affections, in pursuit of the still invisible other forms of loving.

1 “Não é o ângulo reto que me atrai,

Nem a linha reta, dura, inflexível criada pelo o homem.

O que me atrai é a curva livre e sensual.

A curva que encontro no curso sinuoso dos nossos rios,

nas nuvens do céu,

no corpo da mulher preferida.

De curvas é feito todo o universo,

O universo curvo de Einstein.” – (poem by O. Niemeyer)

2 BUTLER, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge, 1990

3 “Para viver um grande amor

Primeiro é preciso sagrar-se cavalheiro

E ser de sua dama por inteiro

Seja lá como for

Há que fazer do corpo uma morada

Onde clausure-se a mulher amada

E postar-se de fora com uma espada

Para viver um grande amor.” (verses of “Para Viver um grande amor”, by Vinicius de Moraes)

4 NIEMEYER, Oscar. Playboy interviews Oscar Niemeyer. Interview with Zuenir Ventura. Playboy. São Paulo, number 185, p. 39 to 58, November,1990. p.43

Mariana Meneguetti, Rio de Janeiro (1989), is an architect based in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. She co-founded Entre, a collective of architects with whom she researches architecture and its urban transformations through verbal reports, having co-authored the publication “8 Reactions for Afterwards”, Rio Books (2019) and “Entre: Interviews with Architects”, Vianna and Mosley (2013). She participated in Walls of Air, the Brazilian Pavillion for the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale, the X São Paulo Architecture Biennial and the XIII Buenos Aires Architecture Biennial. Through an interdisciplinare approach, she maintains an ambivalent practice between research and building practice.