Ashef Lshtshfum

JDA Winslow

I write bad jokes. Bad jokes are more interesting than funny ones. Here’s one: Q: How does Jason Bourne know he’s Jason Bourne? A: Because he is Matt Damon. To get it you need a fair bit of background information.You need to have seen at least one of the Bourne films, unless the one you’ve seen is […]

I write bad jokes. Bad jokes are more interesting than funny ones. Here’s one:

Q: How does Jason Bourne know he’s Jason Bourne?

A: Because he is Matt Damon.

To get it you need a fair bit of background information.You need to have seen at least one of the Bourne films, unless the one you’ve seen is The Bourne Legacy, in which case you need to have seen two. An even more niche version would go like this:

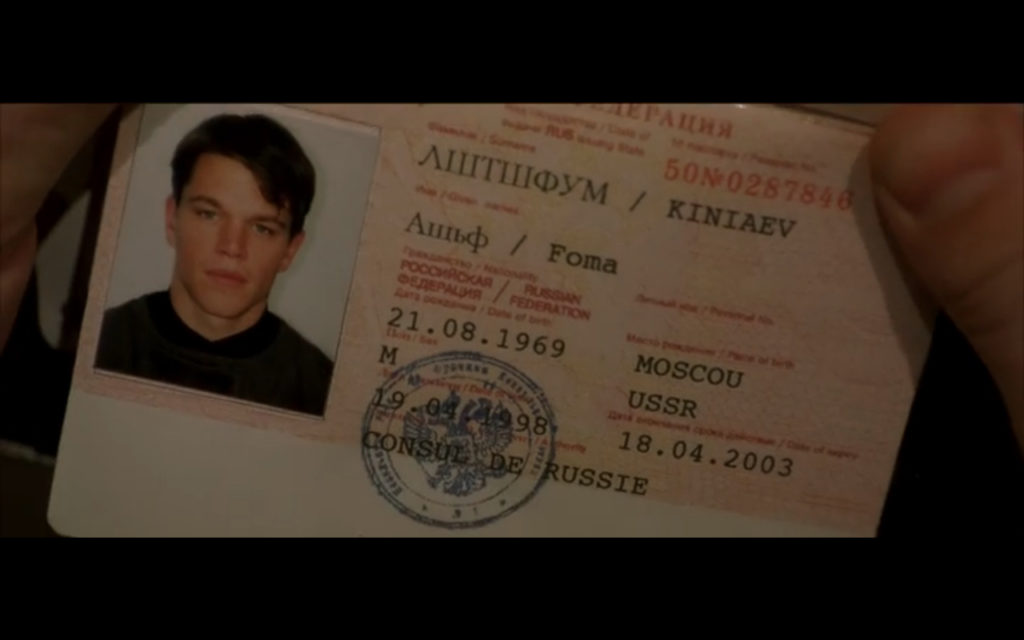

Matt Damon stands in a room in a Swiss bank, looking at the safety deposit box he’s looking down at. He stares at the passport in his hand. The camera zooms in, shows the text. He speaks. “My name is Lshtshfum. Ashef Lshtshfum.”

That joke isn’t mine. It’s something you see in the comments section of a clip on YouTube of Bourne opening up the safety deposit box. This scene of The Bourne Identity is the one where we learn, diegetically at least, the protagonist’s name. Of course, in the original he decides he is Jason Bourne because the passport is the first one he finds, the American one. Underneath he finds the rest, the Brazilian, the French, the Canadian, the Russian. The Russian passport has two names. First, in the Latin alphabet, there’s Foma Kinaev. Foma’s a credible Russian name. Secondly, written in Cyrillic there’s Ащьф Лштшфум. When I look down at my MacBook now, as I’m writing this, I can see how it would happen. About four years ago I spent a happy hour or two carefully sticking down transfers of Cyrillic letters onto my keyboard. Where the letter F is on my keyboard I have a small cyrillic А. Where I have o I have Щ, the soft sh sound. M has Ь, the soft sign, and so on. The Bourne Supremacy’s goof then could be read as just that, a goof of hitting the same place on a keyboard, even when the keyboard’s layout is changed. I’d argue that, goof and all, it’s also something more. It’s a kind of entry point into a whole new version of Russia, a Russia that exists only in Hollywood movies, only those made since the fall of the Soviet Union. After the end of the Cold War the ideological certainty that Russia was the bad guy begins to fall apart a little. We’re presented instead with a new rendering of a new Russia. It exists in a series of spaces, in decadent bars, derelict basements and bleak Khruschev-era apartments. It’s not confined to Russia alone, but spreads outwards, signified by a new kind of language. This language takes Russian as a starting point, but is spoken only by our friend Ashef. Here I try to map these tropes, to make manifest the Western assumptions present in these depictions of an idealised Other. I show a new route through these spaces as they appear again and again on YouTube, pushed up by an algorithm that says “here, try this.”