Saint Bernard. Master of the Cistercian’s body

Edoardo Cresci

Saint Robert, in 1075, dissatisfied with his experiences in the monasteries of Moûtier-la-Celle, Saint-Michel-de-Tonnerre and Saint-Ayoul, founded the Abbey of Molesmes after having retired for a period with some hermits in the Forest of Collan. Molesmes quickly flourished, attracting many vocations and a great deal of wealth, but Saint-Robert, who knew that “virtue and wealth […]

Saint Robert, in 1075, dissatisfied with his experiences in the monasteries of Moûtier-la-Celle, Saint-Michel-de-Tonnerre and Saint-Ayoul, founded the Abbey of Molesmes after having retired for a period with some hermits in the Forest of Collan.

Molesmes quickly flourished, attracting many vocations and a great deal of wealth, but Saint-Robert, who knew that “virtue and wealth do not remain associated for long”, and who preferred a poorer and more isolated life in closer contact with God, in 1098, left Molesmes to found a new monastery in the Forest of Cîteaux.

The monastery and the Order of Cîteaux were founded from the desire for a more sincere adherence to the Benedictine Rule, a desire for a true ‘re-form’: not inventing anything but returning to the purity of the source, only in this the Order can be said ‘new’, the Cistercian ideology does not want to add anything, it only cuts away and purges. The construction of Citeaux was meant to be nothing other than a purified Cluny, the ‘new’ monastery was intended to be a hermitage and a cloister at the same time, and the brotherhood of monks wanted to be a close-knit family that adopted, as if it were a single body, the life of the perfect recluses.

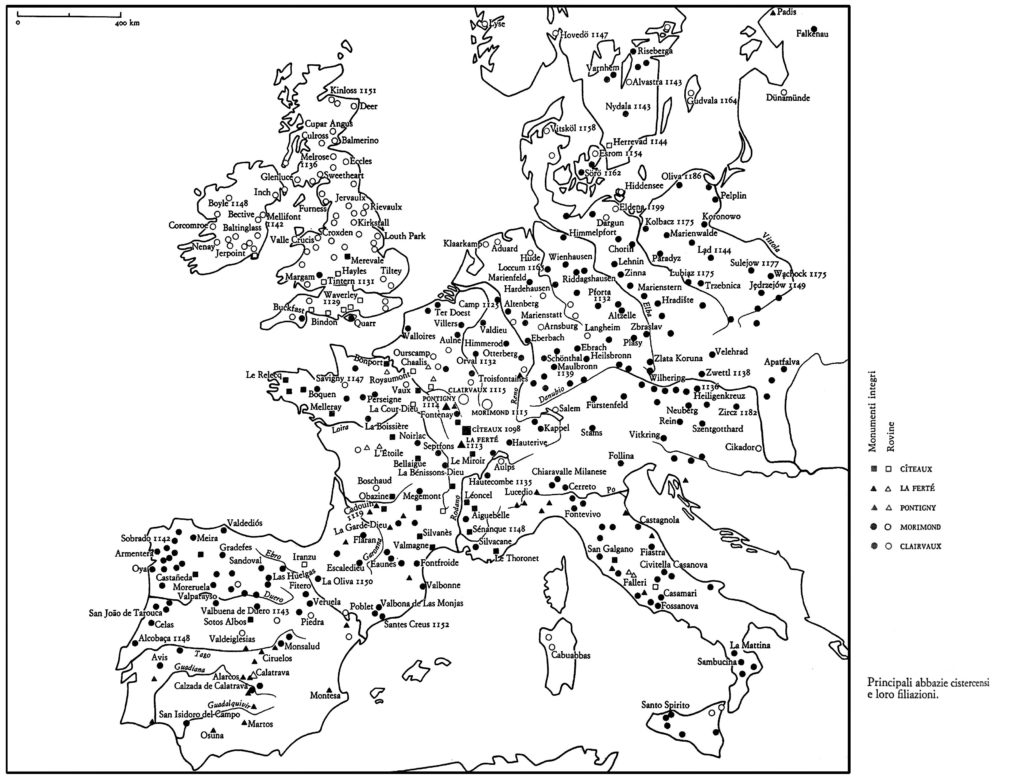

For fourteen years the Monastery of Cîteaux was growing in the middle of the Forest when Saint Bernard arrived there, only two years later he left Saint-Robert to set up another new monastery: Clairvaux. And thanks to Bernard after Clairveaux had put down solid roots it became, in turn, prolific, spreading in Trois-Fontaines, Fontenay, and Foigny. From his monastery Saint Bernard started speaking to the entire Christianity, his ‘sermons’ were in fact not spoken but written, because his exhortations were addressed to the whole world and to those who would come later. His word made the Cistercian Order flourish.

Saint Bernard, who never learned how to handle weapons except his word, was actually a true ‘fighter’, always on a ‘warpath’, using every stratagem to conquer noblemen and knights, trying to make them better people, to push them to cultivate their good qualities and eradicate the others. Like Saint Bernard, the Cistercian Order became a ‘conqueror’, solitary and far from the streets but a living structure that expanded itself to absorb the whole of society.

After the death of the Saint, the Monastery of Clairvaux had founded other seventy abbeys and if we consider those that Bernard’s activities had led to join his family Clairvaux had one hundred and sixty-four ‘daughters’. It was thanks to him,that the Cistercian lineage had pushed its vanguard to the borders of Latin Christianity and became such a coherent, large and widely diffused complex, physically built by thousands of men divided into small teams, who were brought together by a large cohesive institution, ‘white monks’, whose voices had merged in unison in the singing of a choir, and who were buried without an epitaph in the bare earth on the very site of their toil, among the stones of the construction site.

Saint Bernard did not build anything himself, but in reality, Cistercian structures owe him everything. He was truly the patron of that vast construction site, he was, as they say, its maître d’oeuvre. His word governed the art of Cîteaux because this art was inseparable from his morality, from an interior structure that he embodied and that he wanted to impose on the universe at any cost. For him, both life and art had to be primarily founded on the word, and above all, on the word of the Bible: the material on which, and with which, he ‘built’ the entire Order. It is with his words that he shaped the model to which the Cistercian constructions had to conform, as projections of a dream of moral perfection.

When it came to building the white monks always followed the same guidelines, all the Cistercian art owes in fact its unity to that of the Order, which sealed all its architecture from Scotland to the Holy Land in one familiar atmosphere. The monasteries, however, were never identical, or just copies of other constructions: every new building followed the same examples, the same typology, but it also adapted to the uniqueness of its particular context producing a multiplicity of solutions held together by the unity of the Rule.

The work in the field, as well as the work in the laboratory and on the building site, was a fundamental part of the life of the monks and it was never a simple ‘keeping busy’, an economic or sustenance issue. It was a question of an incessant effort for erecting a more beautiful and flawless world. The austere buildings of the Order were for this reason conceived as perfect tools, works from which all excess was banished, and which consequently were good, and therefore beautiful, since for Bernard there was no discord between ethics and aesthetics.

Saint Bernard, in a pamphlet directed against Cluny wrote: «But in the cloister, under the eyes of the brethren who read there, what profit is there in those ridiculous monsters, that marvellous and deformed comeliness and that comely deformity? […] here we are more tempted to read the marble work than our manuscripts, to spend the whole day contemplating these curiosities rather than meditating on God’s law».

For Bernard there was a strong need to reduce everything to its fundamental features, to the strictly necessary, to bare structures and forms, the monk had to do away with anything that was superfluous. Saint Bernard also rejected images: it was too easy for them to shift our attention, distancing themselves from their only legitimate purpose, that of finding God. In 1150 the General Chapter of the Order prescribed: “We forbid the placing of sculptures or paintings in our churches and in other places of the monastery, because when you look upon them, the usefulness of good meditation and the discipline of religious gravity are often overlooked”.

The abbey, and each physical or spiritual ‘body’ of the Order, only desires to be the incarnation of the sacred Word, of the Rule, no more, and in this it becomes a construction ‘pared down to the bare bone’, reduced to ‘skeletons’. The church, as all other buildings of the monastery, let itself be seen naked; humbly, it finds the beauty in the stones reduced by the precise cut, by the rigour, united by the delicacy of their joints, by the cohesion of the same material chosen for all the parts of the building.

The only decoration —if we can speak of a decoration— is the light, parsimoniously distributed, also naked, not covered with jewelled robes as in Saint-Denis.

In the monastery, as in the people it protects, a connection is in this way established between the carnal and the spiritual. All the buildings of the abbey become part of the bigger body of the Order and at the same time part of the soul of the land. The Cistercian house becomes seat of the faculties from which every action proceeds; for this reason until it is not built the Order cannot exist, for this reason the pioneer monks immediately work to build it on the first day of their arrival on the site of the new monastery.

If the Cistercian construction was so successful and as extensive as we can still observe today after being destroyed so many times, it is because the lifestyle sketched by Saint Robert of Molesmes, and then fixed, purified, inflamed and projected to the four corners of the world by the word of Saint Bernard, met the expectations of a rapidly changing society. The Cistercians, who initially rejected the stately system, enthusiastically put the emphasis on a social structure based on orders, and on this they based their worldview and their ‘structures’; for this, at the end, the success of Cîteaux did not survive the disintegration of the society of the three orders.When the scheme of the three classes disintegrated, allowing the idea that it is up to each of us to build our own salvation, that it is not obtained through the mediation of others, Cîteaux withered.

What Saint Bernard had built, for it to bear fruit, had then to come out from the desert of the monastery. In the momentum of the twelfth century, it was no more possible, as Bernard had dreamed, to attract all humanity towards the retreat of prayer folded in on itself to impose its order, its structure, on the whole world from the depths of his monasteries.

Cîteaux died, and today, all that remains is its shell, which is all the more moving precisely because it is empty. However, we still can imagine the Cistercian apses filled with possible germinations, the perfect bare walls with their stones joined together to form a crystal of an ordered universe, as still being fertile.