The word ‘window’, etymologically rooted in the Old Norse vindauga, was for early Germanic peoples just an unglazed hole in the wall or roof that permitted wind to pass through. Most Germanic languages later adopted a version of the Latin fenestra, to describe a glazed version of the ‘wind eye’. European law imposes more severe building regulations […]

The word ‘window’, etymologically rooted in the Old Norse vindauga, was for early Germanic peoples just an unglazed hole in the wall or roof that permitted wind to pass through. Most Germanic languages later adopted a version of the Latin fenestra, to describe a glazed version of the ‘wind eye’.

European law imposes more severe building regulations with regard to the insulation and accompanying ventilation of buildings, eventually resulting in so-called ‘Passive Buildings’; a machine connected to ventilation ducts filters and refreshes the indoor air without too much energy loss, using little electrical energy. While inhabiting the building, one is thus less connected with the natural elements. We think the more radical vindauga situation is not problematic, but rather functions as an inspiration to design intelligent fenestrae – machines without electricity – that assure a healthy, tempered indoor climate resulting in engaged ‘Active Buildings’.

Detail Miracle of the Relic of the Holy Cross in Campo San Lio, Giovanni Mansueti, 1494, Galleria dell’Academia, Venezia

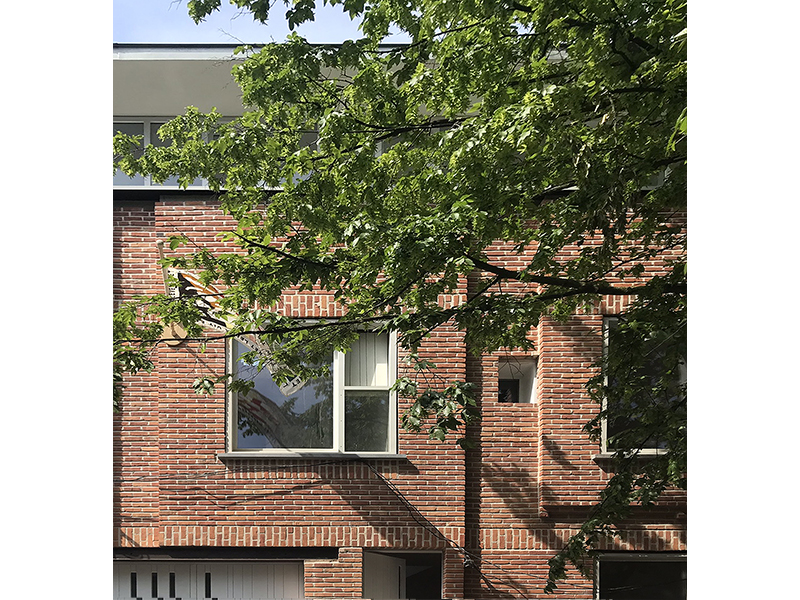

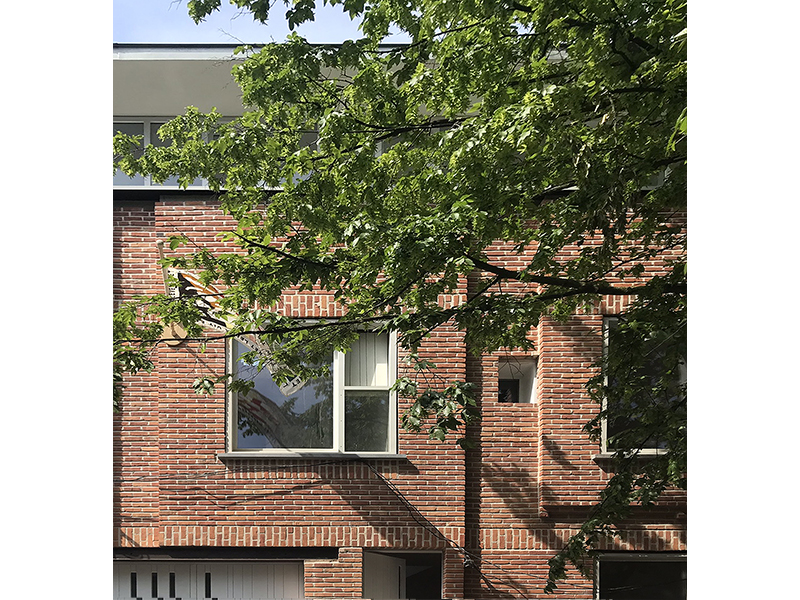

Detail Renovation of House and studio Phlips, Marie-José Van Hee architecten, 2014-2019, Ghent, photo Sylvie Cosyns.

Marie-José Van Hee and her team of architects renew the tradition of building timeless architecture. Throughout her career, she has devoted particular attention to space, natural materials and light, and has made use of classical elements such as the window, door, fireplace and staircase to anchor the house, the public building, or even the city. She has long been connected with the Sint-Lucas School of architecture and taught at the ETH Zürich in 2016.

Sam De Vocht has been a close collaborator of the studio since 2005 and is a guest teacher at the TU Delft since 2016.