Dear Guillaume, dear Jef,

I am extremely happy we will be able to register the continuation of the discussions we have started in a productive way.

There is no need for a lengthy introduction: we will discuss our views on the future of learning Architecture.

In the exchange (3 rounds of emails), I hope we will be able to tackle this topic in its different dimensions, maybe even drafting an experience map of a future student’s experience?

To start–assuming addressing the “why?” of learning architecture would be too large a topic for this format–I would like to focus on the “what?” What should future students take away from a learning experience?

A couple of years ago, in the frame of the “When Socrates Was An Architect” podcast, I asked a derivative of this question to Christoph Lindner, Deborah Berke, Dick Van Gameren, and Maarten Delbeke. The answer was something along the lines of “students should develop their curiosity.” This was a safe, satisfactory answer within the context of the podcast and keeping in mind that the interviewees were mostly deans representing an institution: highly curtailed in their criticality… Here we are free so I encourage you to make the most of this freedom and go for the edge.

To start the dance, I will repeat what I stated already in one of our previous discussions, I would say that students should come out of a learning experience understanding how to tackle the questions posed by the experience in cultural (technical/aesthetic) terms and understanding the consequences of their proposals. Two things: (1) I am assuming this learning experience entails a design exercise and (2) please do not read “consequences” as something pejorative.

So what?

Very much looking forward to your thoughts,

Francisco

…

Dear Francisco, dear Guillaume,

Thank you for this invitation. Very happy to continue our conversation in a format that allows for a slower and deeper exchange, something increasingly rare in the accelerated ecology of academia.

When we ask what architecture students should learn, I find it less interesting to list competences than to describe the kinds of intelligence we want to cultivate. Architecture has never been only about building; it’s about constructing ways of thinking, sensing, and acting in the world.

I think students should walk away from their “learning experience in architecture” with three interlocking dispositions:

a) An inquisitive mindset.

To learn architecture is first to unlearn obedience. Every brief, every program, every “problem” hides an ideology. Students must be trained to question the question itself, not just to answer it. Curiosity is not enough, we need dissent, the audacity to destabilize assumptions and re-code constraints as opportunities. The most dangerous architect is the one who never questions the premise. Architecture starts when we ask why this problem, for whom, and under what assumptions? Learning to doubt productively, without cynicism (!), is the basis of intellectual autonomy.

b) A synthesizing mindset.

Architects must operate across worlds and disciplines that refuse to speak the same language: between technology and ecology, culture and computation, form and politics, etc. etc. This doesn’t mean knowing everything: it is not so much about encyclopedic knowledge, but the ability to relate and synthesize, to hold together multiple, sometimes contradictory systems of thought, and to act as the “glue” between them. The architect’s strength lies in this kind of relational intelligence: the capacity to make sense of the whole through partial and situated knowledges.

c) An imaginative mindset.

And finally, architecture must train imagination as a disruptive force, develop the courage to imagine the possible beyond the probable. Imagination is what lets us build futures that don’t yet exist and alter the status quo. Imagination must be cultivated not as escapism, but as a form of radical realism. The ability to think “what if?” is essential to tackling the possible, to inventing futures that disrupt conventions and shatter expectations.

What do you think? Hope this is helpful/useful to jumpstart the pen pal discussion!

Warm regards,

-jef

PS. I realized after sending my note that I completely forgot to include the obligatory online references. Here they are, and also a brief word on your initial point, which I find extremely pertinent.

I fully agree with your emphasis on the cultural/aesthetic/technical dimension of learning and the awareness of consequences in proposals (eg., in design studios). The ability to anticipate not only how things look or perform but how they act, affect, and transform, is essential. This ethical and cultural awareness, the responsibility for the effects of one’s interventions, should be present and cut across the three mindsets I mentioned.

For the online reference, related to the mindsets, here is are a few (of course, there are many others as well!).

a) On the inquisitive mindset, Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (on critical consciousness and the courage to question the given)

b) On the synthesising mindset, I elaborated on this in the introduction to Transcalar Prospects in the Climate Crisis, i.e. the notion of transcalar thinking and the need to connect across entangled ecological, technological, and social systems.

c) On the imaginative mindset, Donald Schön’s The Reflective Practitioner, Michel de Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life, and Hannah Arendt’s The Life of the Mind: Thinking, i.e. imagination as reflective reframing, tactical invention, and the ethical capacity to think otherwise, to disrupt the given and project alternative possibilities.

…

Dears,

I hope this letter finds you well.

First, I would like to thank Francisco for initiating this opportunity and for giving us the space to pause and reflect—something that is rarely afforded in the rush of our everyday office life.

It’s a precious time, one that we must sometimes carve out or claim for ourselves amidst the constant flow of tasks. A time that, in my understanding, belongs to academia—an environment that operates at its own rhythm.

Francisco, you rightly assert that students should “understand how to tackle the questions posed by the experience in cultural (technical/aesthetic) terms and understand the consequences of their proposals,” to quote you directly.

Jeff, you, in turn, suggest that students should leave with three newly acquired or enhanced dispositions: “an inquisitive mindset, a synthesizing mindset, and an imaginative mindset.”

I believe this is absolutely correct. It’s difficult to argue against any of these points—indeed, isn’t that the way everyone should approach the world?

If more people embraced the outlook and dispositions you both describe, perhaps the state of the world might be in a better place. So far, so good.

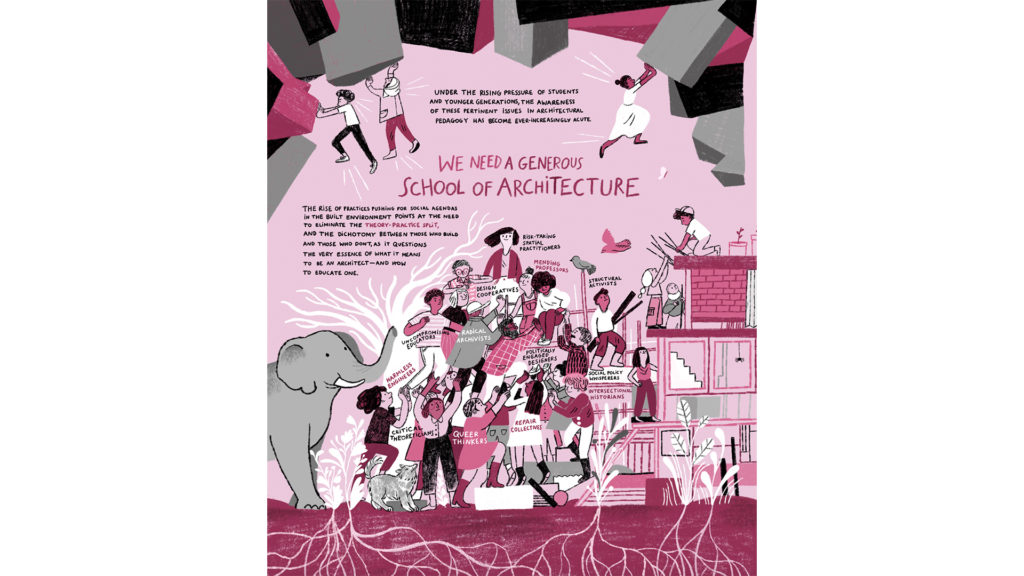

Of course, architecture schools around the world could certainly teach motivated students how to live their lives, but such a goal may prove difficult to achieve.

Or, if architectural education could truly provide all of this, perhaps everyone should study architecture to help create a brighter future.

Perhaps everyone should also read D. Graeber’s and D. Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything, listen to their talks, explore Anna L. Tsing et al.’s Feral Atlas, or watch Adam Curtis’s documentary The Century of the Self.

Such explorations would certainly lead to interesting evolutions. But will that happen? And even if it does, what will all these “enlightened” minds do with this newfound knowledge?

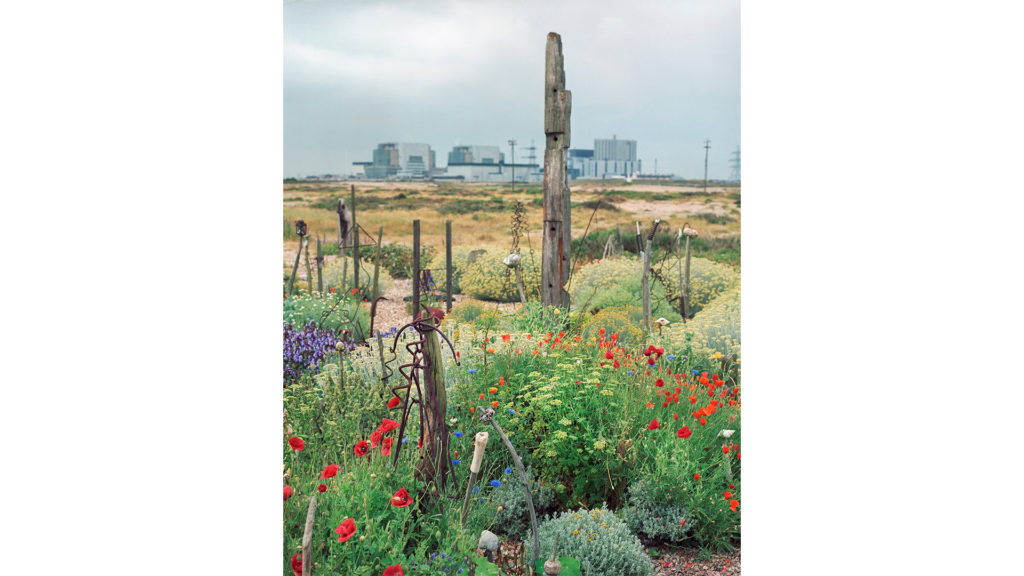

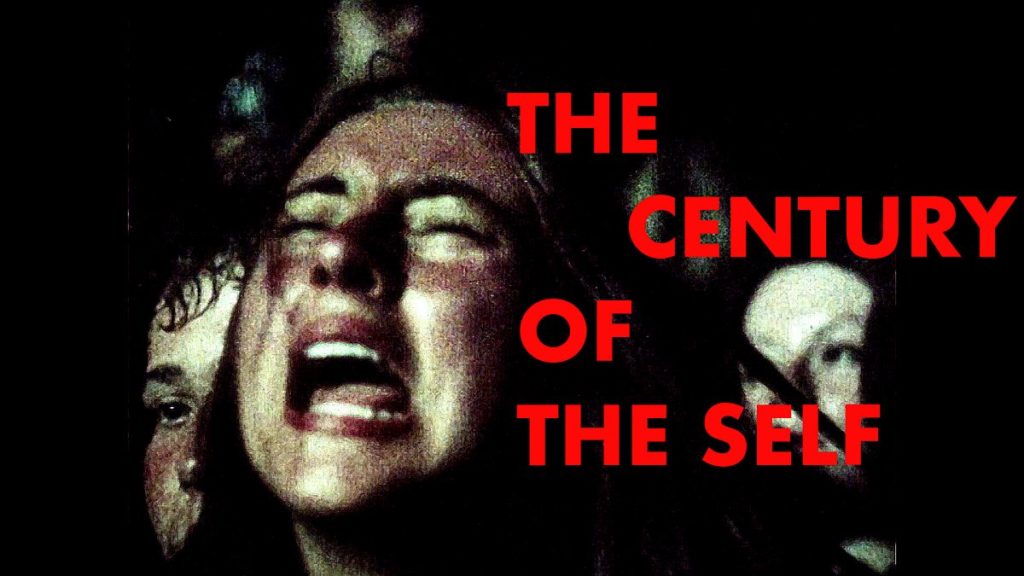

Adam Curtis, The Century of the Self, 2002. Film still.

I agree that architects should maintain—and perhaps even regain—their position as generalists, capable of understanding the essence of constraints, the needs of both humans and non-humans, and the interdependencies within a built environment, whether cultural, technical, or environmental. And I agree that once this understanding is achieved, architects should be in a position to question and propose.

However, in my opinion, what architectural students should take away are sharp, practical tools. They should know how to count, and they should know how to draw. By this, I don’t mean that they must be able to carry out complex calculations without assistance, nor should they be as fast as a seasoned draftsman. But as “economy” is often the weapon of the enemy — by “enemy,” I mean those who sacrifice ideas, disruptive behaviour, creativity, and ecology on the altar of financial profit and accumulation — architects need to be prepared. They need to understand and they need to be able to challenge that « economy ». Drawing – being a universal language that translates ideas into forms – should be next in their arsenal. They should literally learn how to draw, how to translate intentions and ideas into lines and surfaces. Added to that, they should of course know and understand technologies, materials and building techniques. And they should understand their implications in the context of a project, as well as their implications on a broader, much larger scale. In two words, they should be savant and skilled.

And in order to do so, they could start to :

– Question the brief (if there’s one)

– Do some calculations

– Start by copying

– Use geometric principles

– Focus on proportions

– Avoid metaphors

– Prioritize planar projections

– Use a two-steps process (first sketch, than draw)

– Simplify details

– Apply critical construction

– Redo the calculations

– Look with distance

– Question (their own design as well as the entire ecology of actors involved in the project)

– Start over

And what better time than the studies to start to learn all of this ?

Looking forward to your thoughts and answers,

All the best,

Guillaume Yersin

…

Dear both,

I confess I am happily overwhelmed by your replies. It would take more than a simple email to unpack all the potential of your statements…

Therefore I am going to play devil’s advocate and “pick a fight” with one or two aspects I find could lead to some “productive friction”, to quote Patrick Heiz:

A – Does Synthesizing lead to Synthetic designs? Positioning the architect as the capable generalist making sense of otherwise anthagonistic positions is an appealing message for architects as it frames them (us) empowered actors in a welcoming society. Two things about it though:

First, the superficiality and relativisation architects apply in order to “glue” them inevitably leads to the exclusion/denial of certain conditions. Thinking of Architecture as Spectacle and Architecture as overimposed order is still something that makes sense for us who studied in the 90’s and beginning of the 00’s, surfing the wave of the beautiful plastic society, despite our best efforts to reposition the discipline in the current too-late revisioninst movements taking over academia, cultural institutions but probably not reaching large commercial actors. Furthermore, young practices who are now emerging as someone to look at when searching for future references (I can share a list of these later on) seem to be embracing a superficial knowledge of “all” that caters an image/hype-based economy.

Second, architects do not seem to be seen as that by society. Where they ever? According to the latest European Architect’s Council’ study on the architectural sector, architect’s income is generally below that of lawyers, doctors, psychologists, etc. Is this the “Economy”, Guillaume? Synthesize and you get Synthetic. My point is: plastic breaks.

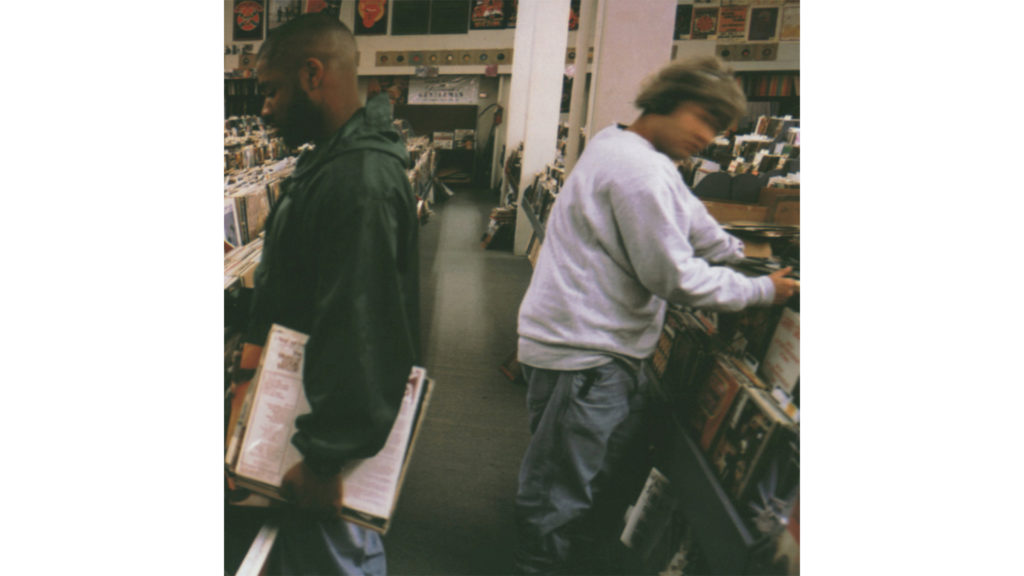

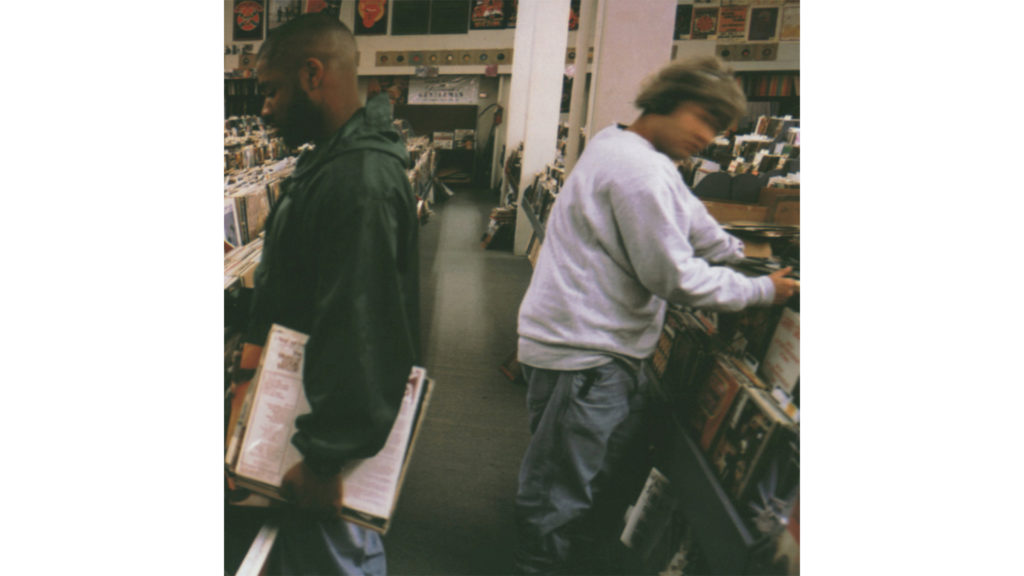

B – Does Synthesizing lead to deeper understanding? I very much like DJ Shadow. He, aka Joshua Paul Davies, did something fantastic: he produced one of the best original albums ever without playing a single note of any instrument or vocal. Everything is a sample. This is only possible through a deep knowledge of what surrounded him and an exciting curiosity about how the enormous mass of the pre-existing can be dismantled and put back together to communicate something new. Virtuosity, brilliance is then in the way something is repositioned and reinterpreted. Synthesizing opens the field in an elastic way. Elastic bends, doesn’t break.

DJ Shadow, “Endtroducing”, 1996.

C – I like your tools, Guillaume. I shared them with my students this week and asked them what they made of it. As you know, I am trying to, as you say, “teach them how to live their lives” in a very literal way: their designs have to directly draw from their own understanding of one of the philosophical schools that deal with the notion of The Good Life. One student pointed out that your tools–any tool–only make sense when you know WHY to use them. In other words, when one doesn’t know how to live their lives, how can they know why/what for to use any tool they might have at their disposal? Or, look at where not questioning the “Why?” but happily falling in line with a pre-established order has brought us.

And something missing: learning towards what? Which Progress? How do we classify the vector, the delta, Jef? Is there a moral frame to approach it or is any progress a valid enterprise?

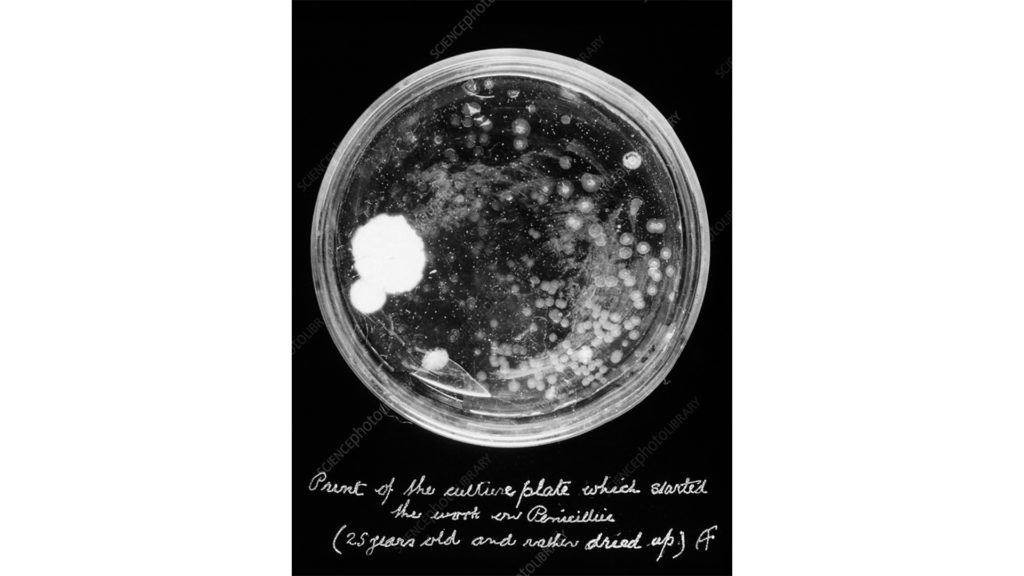

Going back to plastics, a competition launched by a billiard balls producer in 1869 led to the invention of celluloid by John Weslley Hyatt. Fast forward to now and plastics are in our blood.

These are honest, optimistic doubts despite the underlying caustic tone. I can’t wait to see what you make of them!

All the best!

Francisco

…

Dear Francisco, dear Guillaume,

Thank you for pushing me to clarify. You are right: my previous note risked sounding as if the three mindsets I proposed were universal virtues, applicable to everyone in the same way. They are not. I really meant them specific to architecture, to what architects are asked to take on in this world, and to the particular agency architecture can exercise.

Allow me, therefore, to restate them more sharply, and more explicitly, as architectural dispositions.

- The inquisitive mindset: architects as problem-seekers, not problem-solvers

You are absolutely right, and the contrast with engineering is helpful. Engineers, by training and by mandate, tend to see themselves as problem-solvers: excellence lies in identifying an optimal solution once a problem is defined. Architecture, at its best, operates ex ante. Its responsible act is not solving, but posing the problem.

An inquisitive mindset in architecture is therefore not curiosity in the abstract, but the disciplined ability to question what counts as a problem in the first place. Who defines it? Under which assumptions? With which exclusions already built in? This places architects closer to what William Peña described as problem-seeking, rather than problem-solving. Programming, in this sense, is not a preparatory step, but a core architectural act: the reframing of vague, conflicting, or ideologically loaded conditions into something that can be responsibly acted upon.

This is why inquisitiveness is not simply a personality trait, but a professional responsibility. Architects work in zones of ambiguity where obedience would be disastrous. The inquisitive mindset is the capacity to refuse the given brief as a natural fact, and to excavate its hidden values, power relations, and blind spots before a single line is drawn.

- The synthesising mindset: beyond the synthetic, toward the appropriate

Your concern that synthesis risks turning synthetic is well taken. But here, I think precision matters. What I call synthesising is not about smoothing or reconciling conflicts into a marketable image. It is about dealing seriously with irreducible complexity. Architectural problems are rarely optimisable in a single dimension. They require multiple frameworks, disciplines, scales, and actors to interact, often without the possibility of full commensurability. In this sense, architects are not trained to maximize, but to listen, assemble, connect. Herbert Simon’s notion of satisficing is particularly pertinent here: the architect searches for a “good enough” solution that is appropriate across many parameters, rather than optimal within one.

This is also where Guillaume’s insistence on tools becomes essential, not contradictory. Counting, drawing, calculating, constructing, repeating: these are not neutral skills, but forms of resistance against hollow synthesis. Without embodied and material competence, synthesis cannot deepen; it only accelerates. At the same time, tools are meaningless without a reason to wield them. Tools answer the how, but they are blind without a why. The real risk today is not tools themselves, but tools detached from values and telos, becoming instruments of the very economy Guillaume provocatively (or perhaps not) names as the enemy.

Synthesis, understood this way, is about holding together heterogeneity without erasing it. It works less like a seamless fusion and more like sampling: cutting, layering, looping, and repositioning fragments drawn from different domains (Francisco’s reference to DJ Shadow). It implies making connections between cultural meaning, material systems, economics, ecology, and politics, knowing that any decision privileges some values while marginalizes others. This is not superficiality, but a different form of rigour: relational rigour. One might understand this rigorous in the sense articulated by by Karen Barad’s notion of “intra-action,” where relations are not added between pre-existing elements but are what bring those elements into being in the first place. And it is precisely here that shallow synthesis collapses into plastic, while deep synthesis, like a well-composed sample, remains elastic, to remain in your metaphors.

- The imaginative mindset: architecture as future practice

Finally, imagination. This, too, is not evenly distributed across professions. Architects are structurally required to live in future worlds. They must project conditions that do not yet exist and act as if they were already partially real. This speculative orientation is neither escapism nor naïve futurism; it is a professional necessity.

Imagination in architecture operates as a disruptive force. It allows the discipline to estrange the present, to make the familiar questionable, and to propose alternatives that are not merely incremental. Here, imagination aligns with the ability to re-see a situation by projecting different possibilities onto it.

In this sense, architects are not only synthesising what is, but imagining what could be, and testing it against reality. This forward-looking, projective stance is uncommon in many other fields, and it is precisely what gives architecture its political and cultural charge.

—

This brings us back to your crucial question: learning towards what? Which progress?

I do not believe architecture education can offer a single moral vector without becoming doctrinaire. But it must make students aware that every projection implies a direction, and that every direction leaves residues. Plastics, which you already brought up, are perhaps the perfect allegory of architectural progress: a brilliant solution within one problem frame, catastrophic when its consequences are scaled up.

What we can teach, then, is not the right answer, but accountability for directionality. The ability to question problems, to synthesise across incompatible domains, and to imagine alternatives is what enables architects to sense potential residues early, before they become irreversible.

If architects are no longer trusted as generalists by society, perhaps this is because this deeper form of intelligence has been replaced too often by spectacle or compliance. Reclaiming it will not make the profession richer, but it may make it relevant in a more profound sense.

Looking forward very much to the next round.

Warm regards,

-jef

…

Dear all,

As these lines may be the last of this brief but unsettling exchange, I’ll take the liberty of addressing broader aspects of the profession that have been weighing on my mind. These thoughts are tied to teaching and, crucially, to what remains—as this is what you will face once you complete your studies, should you choose to practice in Switzerland, the context I know best.

A profession could be seen as what remains of one’s studies; a residue. To design with residues means accepting the long game. It means acknowledging that architecture and construction are slow processes that mobilize vast resources and leave a profound, long-range impact on people’s lives, the ecology, the economy, and society at large. It is dizzying. At times, the best course of action might be to leave it alone and focus on something else entirely. It is not “preachy” to say that architecture is not the proper domain for the superficiality of the “now.” It is not an activity suited to the zeitgeist, nor to the instantaneity of social media and trends. To chase these is to abandon the distance required for a practice to be critical, contemporary, and truly avant-garde. Without that distance, it is merely “fashionable,” and therefore already passé, as Agamben so brilliantly put it.

Have you noticed that architects are always complaining?

This seems especially true for those in academia (being part of this flock, I’m probably allowed to say so), as they perhaps have more time to dedicate to the task. We complain about clients, teaching, colleagues, society, fees, being misunderstood, being underestimated, our responsibilities, incompetent craftsmen, work hours… the list could easily fill this email and more. This endless whining usually stems from frustration—often a frustrated ego. Yet, it may also be partly legitimate: the architect’s position has lost much of its former radiance. Once seen as a pillar of society alongside the priest, the teacher, and the policeman (what a team!), the architect now drifts between the Kunstproletariat and the service industry, unable to find a comfortable place to nest.

No one bears as much responsibility for this situation as we do. Driven by a craving to build fast and “keep with the times,” we have transformed into “super-service providers.” How else do you win competitions today? You have to deliver: fast, cheap, cool, reused, bio-sourced, resilient, democratic, inclusive, modular, CO2-free. In a competition setting, there is no room to challenge the brief, confront decision-makers, or remain loyal to an inquisitive mindset. The era when a practice could make a living by taking the runner-up spot with a radical scheme that questioned the brief is over. Today, you are asked to be a “super-synthesizer”—capable of playing any rhythm or sample to please the client; a “super-plastic” that allows the project to achieve net-zero.

The myth of the designer’s inquisitive mindset has become a vintage fantasy—a wet dream of the “almighty architect” who sees further than the rest and offers clients what is best for them, even if they are too blind and thick to see it. This was the fantasy of the “starchitects” of the 2010s, who hid pure opportunism behind so-called “critical designs” and “democratic Trojan horses.” No need to name them; we all know who they are.

The only resistance we can offer—if indeed the “inquisitive mindset” Jef describes is required—is to turn down, to refuse. And we must make this refusal public, explicit, and clear. To refuse, and ideally, to propose an alternative path. Consider ZAS in Zurich, who proposed an alternative competition to the official one to avoid a planned demolition by looking at the site differently. The same could be said of House Europe.

What we need are architects who stop whining and start being proactive—using their synthesizing minds to communicate, connect, and inform. But then, I hope for your sake that you have family money to fall back on… because this path won’t pay the bills.

Given the current erosion of architectural fees in Europe—and their dangerous decline in Switzerland—who actually has the time to be inquisitive? The average hourly rate is lower now than when I started my office in 2012. Wake up: who has time to seek out problems when there isn’t even time to solve the pragmatic, technical, and functional issues we’d rather ignore? Who has time to reflect when our services and salaries are slowly being hollowed out? Look at how our beloved (irony intended) SIA speaks about the profession. In Switzerland, even the body meant to protect us has turned into the enemy. And by “enemy,” I mean an enemy not just of architects, but of a peaceful, fair, and just society. A society that should care for its people and its planet is being sacrificed to big capital, speculation, and international concerns.

Rose Eveleth. “When Futurism Led to Fascism—and Why It Could Happen Again”, WIRED, April 18, 2019, via.

I am no romantic; I have no desire to return to some “golden age.” But we must be realistic: to be inquisitive, synthetic, and imaginative, one needs the room to breathe and act freely. That freedom may soon vanish. Acting freely might be banned before breathing—though sometimes the blocking of the former leads straight to the latter. In our current context, there is no progress, only acceleration. And this acceleration reeks of the Futurists’ old fascination with machines, speed, and raw strength. To me, it does not smell good.

A significant part of the “generalist” nature of our profession was once sustained by time dedicated to thought: rêveries, reading, reflection, and exchanges with peers.

Time to learn, time to understand complex interdependencies, and time to shift one’s perspective to see a situation anew.

This time has almost vanished and currently survives only in one sole place: the university.

And without that time, what remains?

See you soon,

Best,

Guillaume Yersin

Jeffrey Huang is the Director of the Media x Design Laboratory and a Full Professor in both Architecture and Computer Science at EPFL. He began his academic career at MIT and later at Harvard University, where he became Associate Professor, before joining EPFL as Full Professor in 2006. He has held visiting positions at Stanford, Tsinghua University, the University of Sheffield, and Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center, and is co-founder of Convergeo, an international strategic and experience design practice. From 2014 to 2017, he was the Founding Head of Pillar (Dean) of Architecture and Sustainable Design at the Singapore University of Technology and Design. He later directed the EPFL Institute of Architecture (2020–24), and he currently leads the Blue City Innosuisse Flagship project (2022–26).

Guillaume Yersin (Vevey, 1981) studied Human Medicine at the University of Geneva. After obtaining a Bachelor in 2003, he then studied architecture at the ETH Zürich and at the Tokyo Institute of Technology. After experiences at Lacaton & Vassal in Paris and AMO in Rotterdam, he obtained a MSc. in Architecture from ETHZ in 2009. In 2012, he founded his own practice SAAS sàrl in Geneva. In parallel, Guillaume maintains his academical engagement as intense as possible. He has been teaching at ETH Zürich (2011-16), at TU Wien (2021-22), and at FHNW Basel (2024-25). He has been repeatedly invited as a guest critic at EPFL, HEAD, ETHZ and HEIA-Fribourg. He is currently Guest Professor at the TU Wien (2025-26).